Published: 5 Dec 2022

Chapter 1

Over there, over there, send the word over there; the yanks are coming……..

They may have been lyrics designed for the First World War and battlefield Europe but were equally as telling for the next adventure. That is if war can be described as adventure and for Australia in that first European war it could hardly have been so, with sixty thousand dead and one hundred and sixty thousand wounded from a population of five million it had been a huge strain on a new nation’s population and resources. For King and country, it was said and fort on soil far from home and for reasons not understood.

This time it was Asia and the South Pacific and on Australia’s doorstep, with Japan’s intentions towards expansion and empire and like the tentacles of some giant gluttonous octopus, its military might was reaching in all directions, draining the lifeblood out of all it contacted, while using countless thousands as slave labour to produce all that was limited in the homelands.

Australia with endless resources was an obvious target for the emerging Japanese Empire but with at least a million American servicemen calling the north east coast of Australia home for the duration; mind you be it not all at the same time, it would be a target too far for Tojo and his greedy entourage. Soon the line of advancement was drawn high in the steamy mountains of the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and along the chain of tropical islands bordering the Coral Sea.

Before the first big bang earlier in the century, the northern part of New Guinea had been described as Kaiser Wilhelmsland and German territory during that country’s expansion of empire. After the defeat of Germany in nineteen eighteen, it had been offered in mandate to Japan by the newly instituted League of Nations. It was Billy Hughes, the Australian Prime Minister who protested the loudest. Any country that controls New Guinea, controls Australia was his call; therefore the German territory was instead mandated to Australia, to be governed with Papua, which was already an Australian colony.

Over paid; Over sexed; And over here;

Some descriptive words aimed in general towards the American soldiers, uttered mostly by those too ignorant to realize Australia was destination for the resources starved Japanese and no matter how it was supposed, without those brave servicemen, their ships and aircraft it could be definitely said Australia would have become nothing but a mining and farming outpost of an expanding Japanese Empire, using the seven million souls occupying three million square miles of the antipodean paradise as slave labour. The women to service the sexual appetite of the Japanese military, as often occurred in Korea and Manchuria. The men to labour until backs were broken and life was spent, as had been obvious on the Burma Rail, or in the coal mines in Japan itself.

Within the tall mountains between the Atherton Tableland and north of the coastal city of Cairns, there lays an area of forest considered by many to be the world’s oldest tropical rainforest, dating back to Gondwana time before continental drift. The forest also once covered that high tableland but a hundred years of white settlement had turned the volcanic soil into rich farming land, while the many small mining and logging settlements flourished to become towns, with road and rail links, carrying minerals and tall timber giants of the forest, down the craggy, almost impenetrable mountains, to the sea and away to southern, or foreign destinations.

The natives had a wealth of stories of this northern paradise that had been past down from father to son, generation after countless generation, of a time when volcanoes burst from the tropical ground like ripe boils. Their dreaming also remembered the flooding of the coast when the sea rose up to drown the land between the great reef and the modern shore but that was long since and now the volcanoes were but deep holes in the rich red soil and the boils turned to lakes of fresh pristine water hidden within an expanse of green forest.

High in those mountains, above the tapestry of farming land you would find a small community built on tin mining and once a busy town of many thousands that stretched across the hills like an open sore, taking away every tree, removing the mountainous topsoil to scratch for mineral.

Long since had that bustling tin-town settled into what could be considered a sleepy village. Although the mining prevailed, machinery now drew tin ore from the ground and not the sinewy hands of the scratchers, while throughout the day and late into the night the battering of rock to mineral echoed from its tin crushing battery.

Now that town and its surrounding hills had become a training ground for thousands of soldiers of both Australia and America, to eventually fight the Japanese in the highlands of New Guinea or the islands of the Coral Sea, as the Imperial army advanced southwards island by island.

The tall mountains to the east began their western downing almost at the first street of that tin town, causing a rain shadow and almost within a matter of a single mile the landscape turned from thick tropical rain forest to dryer woodland. Those mountains also broke up the summer cyclones being too high to cross but occasionally a storm would skirt to the north or south and come from behind and on those occasions the storms arrived with strength causing much damage.

Mareeba was the principal town on the Atherton Tableland and nestled on the downing’s with connection to the port and city of Cairns by a narrow mountain road, clinging to the sides of a deep and foreboding river gorge, cut by the flow of an ancient river. This road followed a railway built for the transportation of tin ore and timber more than seventy years previously. This narrow gauge railway track snaked through the high mountains, clinging precariously to the sides of the Barron Gorge with a multitude of tunnels and escarpments to cross along its winding path, ever downwards to the floodplain and mangroves of the narrow fertile coastal strip. Alongside the passage of the rail tracks on the coastal strip were many plantations of sugarcane, sucking up the high rainfall and endless sunshine of the northern tropics.

Mareeba was considered to be the gateway to the cattle industry of the Carpentaria Gulf country, a vast flat savannah area of thousands of square miles of almost empty wilderness, while but twenty miles higher into the tableland was Atherton and farming on the rich red volcanic soil, set in wet tropical forest. Even higher still were Herberton and Ravenshoe the tin towns. All of which but three years previously were unknown destinations to the majority of Australians and as for our cousins in America, Australia was sometimes mistaken for Austria in Europe, so often prewar mail went the long way around and never again heard of.

Mareeba boasted a large military airfield from where many sorties departed for the front in New Guinea and with Townsville further south on the tropical coast, had been the principle fields during the battle of the Coral Sea in May of the previous year. During the Coral Sea encounter it should be admitted that allied aircraft were in main carrier based and seeing Australia lacked carriers would have been American.

Most of the troops could be found further into the Tableland near Tolga and Herberton, being brought from the many battlefields, often as far away as North Africa, for recuperation and retraining in jungle warfare before being redeployed. Also the area around Herberton and the Walsh River became a practice range for cannon and for decades after the war, live ordnance could be found scatted through the scrub. During the summer and bushfire seasons it wasn’t rare to hear a boom as a twenty-five pound explosive overheated and detonated.

The Tablelands also became home for those evacuated from the coastal city of Cairns and surrounding areas, which by this time in the conflict, were within seven hundred miles from Japanese held territory in northern New Guinea and would be even closer, if the Emperor’s men could not be halted in their advance southwards through the British Solomon Islands. It was strongly suggested that anyone not necessary for defense or the war effort, should leave for safer areas, either to the south of Queensland, or higher into the Tablelands beyond the lofty Bellenden Ker Mountains.

There was also rumor of a Brisbane Line, that being a line drawn on a map north of Queensland’s capital Brisbane, to Adelaide in South Australia; therefore if the evasion of the mainland eventuated, the Japanese could have the north and west, while Australia held the better lands in the south. Such a rumor, although widely believed, was never substantiated as fact but in retrospect made perfect sense.

With the evacuation Cairns became almost deserted. There were entire streets without a soul in house, while belongings and furnishings that could not be transported were put to auction, bringing but a fraction of their worth. Much of what was auctioned was bought by the auctioneers or their agents and stored for resale as profit with the return of better days. Others simply closed the door and walked away, with hope the conflict would soon be at an end and they could return to their tropical, dreamy and isolated existence.

There were exceptions and some, especially the old, refused to evacuate the homes they had known all their lives and as evacuation wasn’t mandatory, they remained in hope the New Guinea front would hold. Such people found life more difficult, especially with the military taking over public halls and school buildings and the constant drone of aircraft, either arriving or departing, while the once quiet streets and roads soon churned into ruts and dust by military vehicles. During the monsoon the roads became bog-holes that were impassable by foot or motor.

Now where children once played games and ran joyfully with their cane play-hoops and dogs, crocodiles became more frequent and brave. It wasn’t rare to see a number basking on the tidal mudflats of Trinity Bay alongside the city centre, without displaying concern for the increased shipping in the harbor Occasionally American Sailors would use them for target practice, leaving their carcasses to rot on the mudflats. They could also be seen about the streets closest to the river and mangroves, in places where the road traffic had all but disappeared.

On one occasion an elderly lady who lived a stone’s throw from the river and bridge leading to the north, discovered a large reptile on her front lawn, when she came out one early morning on her way to the shops. By its appearance it was sizing up her chicken coop but hadn’t worked out how to manage the cyclone wire fence that protected the startled chickens, cowered at the enclosure’s opposing parameter. The reptile remained there until the woman managed to contact a neighbour, to shoo it back to the scrub along a small creek that lead to the Barron River.

How big is it? The neighbour had enquired.

If you like Mr. Snell, I’ll get my sewing tape and go measure it, had been the woman’s laconic reply.

Life on the high tablelands remained much as it had been before the war, only now industry was geared towards supplying the military. Farms that once planted Tobacco now turned to crops for the military kitchens. Also fuel, like most commodities, was rationed and any vehicle that could help the war effort had been commandeered into military service. If not and there was a breakdown, parts were difficult to find, giving inventiveness a free hand and soon bailing wire took pride of place where once bolts and nuts were found.

Soon after the fall of Singapore the Japanese commenced bombing the port of Darwin at Australia’s top end and closest to Indonesia and Dutch West New Guinea, doing much damage and killing many during the sixty or so raids. The first attack came early morning on the Nineteenth February in Forty-three, by almost two hundred Japanese aircraft and was so unexpected that people happily waved, believing they were allied aircraft, until the bombs fell and the aircraft began to strafe the ground with machine gun fire.

That first surprise attack found and damaged a number of ships in Darwin Harbour, firstly sinking the HMAS Mavie an Australian patrol boat, also the USS Peary an American Clemson-class destroyer, killing eighty-eight of its crew. Many more of the fifty vessels in port at the time were also damaged, before the Japanese turned their attention to the town and airfield.

Among the targets was the Darwin Post Office, which suffered a direct hit. Taking cover in a slit trench in the back yard of the Postmaster’s residence were nine members of the Postmaster-general’s Department including the Postmaster, his wife and daughter and all nine were killed instantly with a direct hit to the trench. During that first raid Darwin was caught, as if to speak, with its trousers down, killing more than two hundred military and civilians with many more suffering injury, also destroying most of the aircraft based there while suffering little loss to the attacking aircraft. Soon after the attack the bulk of the aircraft were drawn further south and out of range.

As for the Queensland coast, the peace was soon broken albeit somewhat comical. There were three raids on Townsville, where the only casualty was a coconut palm. Also one Emily flying-boat aircraft flew from the Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain Island and late one night dropped its load at Saltwater near Mossman north of Cairns. One of the bombs destroyed a shed, sending shrapnel through a farmhouse, wounding a child while sleeping in her cot.

Such raids along with what was printed in the daily newspaper about Darwin and the bombing of the pearling port of Broom in Western Australia, put panic into the hearts of those along the Cairns coastal strip. There was suggestion from the military those remaining in Cairns should dig bomb shelters and drill in readiness for an uncertain future. It soon became comical relief to view old men marching out of step up and down the streets along the waterfront using broom sticks as weapons, their uniform the woolen suit and tie of bank managers and school teachers, their understanding of warfare totally lacking.

After the bombing at Saltwater the military placed guards on oil dumps as well as rail bridges and roads leading to the south, making the northern coast a no-go zone for civilians without authorization. Soon after the Cairns waterfront bristled with antiaircraft batteries and buildings of importance were sandbagged, their windows either boarded or taped and the only police presence was military, as they constantly searched the bars and hotels for anyone absent without leave, or drunk and causing a disturbance.

Earlier in that year three Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines had entered Sydney Harbour, firing a torpedo at the American heavy cruiser SS Chicago but the torpedo missed, hitting the shore behind with such force the impact sunk a converted Sydney Harbour ferry, HMAS Kuttabul, killing twenty-one sailors. All midget submarines were either destroyed or scuttled, while the mother ship on its departure, shelled Sydney and later Newcastle inflicting little damage but was most successful in causing disquiet within the community.

Although attacks on Southern Australia were uncommon and the waters of the coast of Victoria mined by both Germany and Japan, further attacks were limited because of distance and heavy allied navy presence, although much later aerial photographs were discovered in occupied Japan, proving aircraft had on a number of occasions, had flown over both Sydney and Melbourne on reconnaissance. Such aircraft were believed to have been floatplanes from Japanese J2 or J3 submarines.

Instead of concentrating on the populous south, Japan continued its attacking of Darwin being closer to captured bases in Dutch Indonesia, also further to the south west on Broom and its pearling fleet. Broom oddly was populated at that time by many Japanese divers used in pearling and the bombing, although light, killed many of their own citizens.

After the battle of the Coral Sea and Japan’s failing in the South Pacific, the north of Queensland expressed a gentle reassuring sigh of relief but there remained many more battles before safety would be secured. Many more aircraft lost from the Mareeba fields and many more Australian troops trained in jungle warfare on the Tablelands, sadly only to die along the Kokoda Track, while pushing Imperial troopers out of the high Owen Stanley ranges and back to the northern New Guinea Coast, then if possible island by island back to Japan.

For now the main concern was how long it would take to push the Japanese back to their home islands but with many it was worry for sons, fathers and uncles who were fighting, almost hand to hand, in the mud and jungle of the high Owen Stanley’s, or in the sands of Tobruk in North Africa. As for the more impressing front in New Guinea it was reported that Japanese soldiers had all but reached the summit of the Owen Stanley Range and from there it was a short distance to Port Moresby the principal city on the island’s southern coast. Then by the next report they had been repelled with great loss on both sides.

Alfred Parker, a Tableland farmer, had as much concern as most of those in his community, as his oldest son and a younger brother were somewhere in the New Guinea killing fields. Sometimes their letters home would bring hope, followed soon after by despair, although both hope and despair were well guarded and because of censorship, condition was never reported at any length. What was written usually amounted to black-humour or requests for anything that would remind them of home and family.

If it could be considered providential, the Parker family was more so than most, as their farm had been contracted to supply vegetables as well as poultry and to a lesser degree pork to the military, while having two further sons and a daughter at home to help run the farm.

Alfred’s second child a girl Winnie, now a young woman was approaching her coming of age, while chaffing to be in town away from the mundane of farm life. Winnie felt passed over, as a number of her girlfriends were already married, or were stepping out with intention. Many to American airmen with promise of silk stockings and other luxuries hard come-by in Australia, or for a new life in far off USA away from the killing fields. Often those relationships ended in tears, or worse, they becoming pregnant to an already married or proposed marine, or to an airman who was soon reposted and missing in action, leaving a family in crisis.

Alfred Parker’s remaining sons, the elder Owen turning nineteen a month after Winnie’s approaching twenty-first celebration, was of military age but given dispensation because of working on the land and having a brother already serving in the AIF. Gavin the youngest and not yet sixteen, although by his assessment close enough to be so, had been turned away from the local recruitment office as underage, on two occasions after being recognized by the recruitment officer.

For Gavin it was the excitement of the uniform and carrying a firearm that fed his imagination, also a number of his friends who weren’t much older had already taken, as if to speak, the king’s shilling. Others like Gavin had lied about their age, managing to fool the recruitment officer, or more to point were accepted without question, as new recruits for the killing fields were becoming light on the ground.

The Parker farm was considered large for the area with good rich soil and close to a small community known as Walkamin on the Mareeba to Atherton road, with its northern boundary a matter of a mile and a tad more from the Mareeba airfield. The farm was prosperous and had been in the family for three generations since late in the previous century.

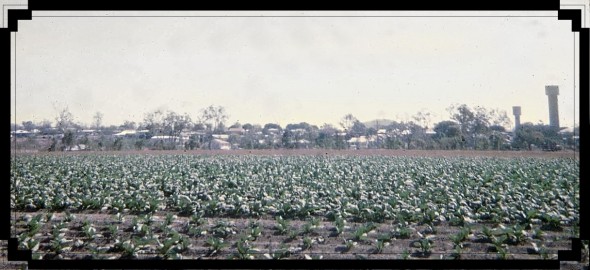

Before the war many of the Parker neighbours had planted tobacco that had been grown in the district since the thirties. Even so it was considered more experimental than a future cash crop for the tableland area and its quality less preferred by the southern packet tobacco and cigarette producers, believing it inferior to that from Virginia. Therefore with the onset of the war, the Parker farm held advantage against others, as it was already producing vegetables, becoming a supplier to the military kitchens and not suffering a delay in planting, while waiting for the first crop to reach harvesting. Also Alf Parker wasn’t a greedy man and accepted the going price, others attempted to skim the cream from the government submission by supplying over priced and substandard produce.

When it came to delivering produce to the military kitchens, Alfred Parker had kept his old Bedford truck and was permitted to draw a small supply of fuel from the depot at the airfield. Many had their vehicles requisitioned, or if not required they found it necessary to run on alternate fuel, some became most inventive in what they used and when it was used café kitchen oil the entire town smelt of fish and chips.

Delivery days to the airfield were often a time of disquiet within the Parker household. Owen the older of the two remaining Parker boys was licensed and had permit to enter the base but often, if he was busy elsewhere the younger Gavin would do the deliveries without being licensed to drive. As Gavin appeared older and was known at the base he was seldom challenged, although their father wouldn’t allow him to drive further into town.

The disquiet was usually brought about by Winnie wanting to ride during deliveries as she, unknown to her father, had become familiar with an Australian soldier who was a guard at the airfield and on a number of occasions she met with Ryan at a local dance night and other familiarization excursions. Even so Winnie was more interested in flirting with the American airmen as they were more cashed-up than the local boys and had advantage of bringing little luxuries back from State-side.

When Gavin made deliveries he was more than pleased to have Winnie ride along with him, as it removed scrutiny of his driving without a permit or license and in exchange he kept quiet about Winnie’s flirtation with the enlisted men. Owen was not as happy having Winnie along, as she spent too much time in conversation, sometimes disappearing for lengthy periods when he should be gone, then on his return having to make excuse with their father. As for Gavin his usual excuse would be extra security at the base, or he was unable to establish the correct officer to sign for the deliveries.

During deliveries when alone, Owen would often park for a brief moment near the gate before entering the field and gaze in wonderment at the many rows of aircraft and their obvious power. He loved it mostly when they fired-up with the roar of engines as the bombers taxied towards takeoff and how such heavy craft appeared clumsy on the ground but found the grace of a bird once in the air.

On this day Owen lingered longer at the gate than usual bringing the sentry to become suspicious. The sentry slowly approaches in cheerless manner, “do you have a problem there young feller’?” he questions while standing on the truck’s running board for a better view inside the cabin, his rifle bashes clumsily against the door in a most unmilitary fashion and Owen notes the safety catch hadn’t been activated.

“No problem mate, I was watching the bombers taking off; are you trying to shoot yourself?” Owen questions with a nod towards the rifle.

“What’s your point kid?”

“The safety catch.”

The soldier activates it without comment; “aren’t you Alf Parker’s oldest lad?”

“Second, my brother Jim is somewhere in New Guinea fighting the Nips,” Owen answers as the last aircraft in line lifted from the dusty airstrip.

“I haven’t seen your Winnie around of late,” the soldier says.

“Would you be Ryan?”

“What if I am?”

“My younger brother Gavin said you have been seeing Winnie.”

“Was, I would say is more the correct tense,” there is an air of rejection in Ryan’s tone.

“That is women for you,” Owen all but laughs at the soldier’s obvious misfortune.

“I hear she prefers the yanks,” Ryan says and noticing the corporal pacing towards the gate as he steps away from the truck.

“I couldn’t say,” Owen replies.

“Off you go lad you are holding up the war,” Ryan loudly commands and waves the vehicle through but as Owen enters, Ryan is strongly chastised by the duty corporal, whose tone is as heated as the Mareeba weather and heavily flavored with vulgarity.

‘So that is Ryan?’ Owen thinks as he reaches the kitchens.

‘Not a bad looking feller’ but Winnie could do better.’

Moments later he is met by the officer of the day and any thoughts on Winnie’s choice quickly evaporate away.

After his deliveries and as Owen prepared to leave, there is a loud roaring above his head as a Liberator bomber passes over the airfield at a perilously low altitude. Looking up he notices a starboard engine is all but shot away and a second engine is trailing smoke. The aircraft has enough power remaining to again circle the airstrip and approach from an alternate direction but on its attempt to land, overshoots and ploughs into the soft earth beside the strip, ripping off a port engine before coming to rest close to a number of large trees within a cloud of dust and leaf litter. The smoking engine then bursts into flame as a fire truck arrives. The fire is soon controlled, while the Liberator’s crew, or to point, those remaining upright, stand well back watching the procedure.

“Lucky,” someone shouted on seeing the incident, as a second fire trucks hurried towards the bellowing smoke and dust. With the fire extinguished many from the field gather about as two apparently wounded airmen are stretchered to a waiting ambulance.

“Come on kid, there is nothing for you to see here,” a soldier demanded as Owen remained close by watching the ordeal.

He is then escorted from the base by the overzealous officer.

Arriving back at the farm Owen is met by his brother Gavin, who after managing the gate climbed into the cabin.

“You’re home early?” Owen suggests realising it was a school day.

“We were given a half day, something to do with using the school grounds by the military and Steve Evan’s old man gave me a lift, as he was in town getting supplies. Did you see the Liberator?” Gavin excitedly gushes.

“I did and it crash landed at the south end of the strip while I was doing the deliveries.”

“Anyone killed?”

“I would think not from the crash landing but it was badly shot-up, who knows what the poor buggers are like inside and for what I could see there wasn’t a full crew standing about as the firemen doused the fire.”

“Gee I wish I was there. It was so low over our house you could almost touch it.”

“Touch it Gavin?”

“You know what I mean.”

“Is dad home?” Owen asks.

“He’s up the paddock with the tractor. I saw a mate of yours at school this morning.”

“Who would that have been?”

“Bazza McPherson.”

“What was Barry doing at the school?”

“He’s now with the fire department and came with his boss to give us a talk on joining the brigade.”

“What did Barry have to say for himself?”

“Not a lot, he mostly stood around holding up photographs of fire trucks and hoses while trying to look important.”

“He was more Jim’s mate and they played rugby together but because of some medical condition he couldn’t enlist when Jim did.”

“I’m gonna’,” Gavin blusters.

“You are going to do what?”

“Enlist!” Gavin’s declaration came with an increased level of bluster as he waited for his brother’s reaction.

“Don’t you let mum hear you say things like that, besides you are still too young.”

“I’m good with a rifle, I can knock over a tin can at two hundred yards and they need men with a keen eye.”

“Men and not overexcited boys and I think you would find shooting tin cans down the creek with a twenty-two, isn’t the same as shooting Japs with a three-o-three, while they are shooting back at you. Have you ever fired a three-o-three?”

“No – so?”

“I have and they have a back kick like a mule.”

“Still.”

Owen laughs at his brother, “Still,” he mimics.

“If you can fire one so could I.”

“I guess you could but enough of that. Ryan was on guard duty at the gate and he asked after Winnie.”

“I don’t think Winnie is sweet on him anymore,” Gavin says.

“Why?”

“She likes the Yankee Fly-boys.”

After garaging the truck Owen enters the kitchen where his mother is preparing the night’s meal. The day is hot and much of her auburn hair had escaped from being tied behind her head and trailing in long strands down her sweat beaded face. She huffed at the extra heat from the stove and jumps as Owen speaks from behind.

“Oh you frightened me; you shouldn’t sneak up on people like that Owen.” She paused from her work and returned the loose strands of hair to the tie but almost immediately they fall back.

She puffed them away with a deep sharp breath.

“Next time Megan-may I’ll sound a bell – ding dong, ding dong – beware son approaching.”

May gives a gentle smile but doesn’t respond to his asinine remark, as even as a young child Owen referred to his mother by her name and not that of mum or mother. Mostly she was known by her second name being May but Owen was in the habit of running both names together in quick succession to become Megan-may.

“What’s cooking?” Owen asks while lifting the lid on a large simmering pot.

He sniffs at its contents without surprise.

“Some call it Irish stew.”

“What do you call it?” Owen asks.

“I preferred to call it casserole, although with meat restrictions, it is mostly leftovers, until we received our next ration coupons,” May explains without enthusiasm as she takes the pot’s lid from Owen’s grasp.

“Isn’t it about time dad killed one of the porkers?”

May ignores her son’s suggestion as she gives the pot a quick stir and returns the lid; “there’s a letter from Jim on the table.”

“What has he to say about the war?”

“Nothing about the war or little else, as most of it has been inked out by the army censor and it took almost a month to get here, he does ask for me to buy something nice for him to give for Winnie’s birthday.”

“At least he was alive when it was posted,” Owen amends with hopefulness.

May gives a sorrowful breath.

“What has happened?” Owen asks sensing his mother’s building distress.

“I had a telephone call when you were doing the deliveries from Meg Rush about her Nephew Trevor.”

“I know Trevor he signed up with Jim and I was at school with his brother James.”

May drew to silence giving Owen a feeling of foreboding.

“What has happened?” he softly asks.

“Trevor was killed at some place called the Kokoda Track. I think it is in New Guinea.”

“Oh, he was in Jim’s regiment. When did it happen?”

“She didn’t say but from what I can gather, it was some weeks back, she only received the telegram this morning.”

May steps from her cooking; her head bowed away from her son while appearing to be crying, as it was a constant in such times to fear the arrival of the telegram boy, with his grave face and slow pace as he approached to perform his regretful duty.

“Jim will be alright mum,” Owen attempts to assure.

“When will it all be at an end?”

Owen didn’t answer as there was nothing he could say that would give a mother assurance towards the safety of her child. All they could hope for was a further letter from Jim, again censored but at least assuring his safety.

“I concern for Gavin,” May quietly utters.

“Why so?”

“Twice now he has attempted to enlist.”

“Yes but they soon realized he was underage and sent him packing.”

“What if he tries to enlist outside the tablelands where he isn’t known?”

“I can’t answer that,” Owen quietly responds.

“You will tell me if he has such intentions.”

“I’d give him a thick ear first,” Owen promises but refrains from repeating his brother’s earlier remark.

May returns to her cooking, “oh well,” she simply concludes knowing there was little she could do except worry, “where is your father?” she asks.

“I heard the tractor going.”

“Go and let him know I’ve put the kettle on and he hasn’t been down for his lunch as yet.”

Owen shouts over the roar of the tractor’s motor bringing his father to turn it off. He approaches and places a hand on the motor, “it’s overheating again,” Owen says.

“It is playing up a little but as long as it isn’t run for any length of time, then it is okay.”

“Did you order the part?” Owen asks.

“I did but with the war who knows, possibly it will never arrive. Maybe I could have Ken Francis make up the part.”

“Could Ken make it?”

“He is good at that kind of thing. Was everything alright with the delivery?” Alfred asks being his habit each time his son returned from his deliveries, as those at the base kitchens were prone to complain about most and refuse much, although they would keep what was refused without payment, saying best to keep it, rather than return to be fed to the farm pigs.

“No one said anything.”

“Good lad. I would like you to run into town for me tomorrow and as Gavin has the day off school for marking day you can take him along with you.”

“No worries, what for?”

“I owe Sid Burrows two quid from last Friday night at the pub and promised I’d give it to him by yesterday and on the way you will have to stop at the depot for petrol.”

“I had trouble getting petrol last time,” Owen admits.

“If they want vegetables delivered then they have to supply petrol as it is part of the contract.” Alf removed his hat and with the sleeve of his shirt wiped his face clean of sweat and grime, “pass me the water bag will you son.”

“It’s empty, I’ll go fill it.”

“No matter, I’ll come up for lunch.”

“It is almost dinner time; mum has just now put it to the stove.”

“Stew,” Alf but whispers and gives a known smile.

“Correct in one,” Owen agrees.

“Is your sister home?”

“No, Winnie caught the rail motor into Mareeba with Robyn Tuff, I hear there is a dance at the town hall tonight and they are going to stay overnight with her friend Pam.”

“Who is Pam?”

“Pam West; she works at Jebreen’s.”

“That girl,” Alf growled and climbs down from the tractor. “Come on I’ll walk back with you.” Alf glances up into the cloudless sky, “we could do with a drop of rain, or that planting of lettuce will need to be hand watered,” he says.

“Why bother they don’t come to much with our climate, it is much too humid for lettuce.”

“The base asked me to try growing a crop, as by the time they arrive from elsewhere, they are unusable.”

“Anyway isn’t lettuce a little fancy for enlisted men?”

Alf ignores his son as they slowly return to the house, “yes tobacco,” he softly says for no apparent reason and again searches the cloudless sky for any trace of rain.

“Why say tobacco dad?”

“After the war I think we will give up on vegetables and have a go at growing tobacco.”

“Did granddad ever grow tobacco?”

“No, he hated the stuff and didn’t smoke. Back then it was only an experimental crop up this way, although it had been grown down south for quite some years. Even way back into the eighteen hundreds I believe.”

“Here in Queensland?”

“Yes at a place oddly enough called Texas, also at Myrtleford in Victoria but it is said that Mareeba has the better climate and soil for the crop.”

“Won’t that mean updating our equipment and building a curing barn for the leaf?”

“Yes I believe we can afford to do so and Ken Francis’ father grew tobacco in the thirties, I’m sure Ken could give us a few pointers. What do you think Owen?”

“I’ll leave the thinking to Jim when he returns from the war.”

The front door creaked open distracting May from setting the table, “is that you Gavin?” she asks.

“No it’s me,” Owen answers.

“Did you call your father?”

“I’m also here,” Alf answers, “I’ll go wash up.”

As Alf returns he spies the letter from Jim, “what has Jim got to say for himself?”

“That he is well and missing a good home cooked meal, little more but I would love to be able to read what the army has censored.”

Alf collects the letter and holds it up to the light, although nothing is visible through the many lines of dark ink. He smiles towards his failure and his son’s attempt to share more than the army would allow.

“I had a telephone call from Meg Rush this morning,” May quietly says.

Alf waits for May to continue, expecting the usual gossip about this one or that, as Meg Rush was well known for her ability to uncover any inkling of scandal within the district.

“It was about her Nephew Trevor Wilson.”

“Oh,” Alf simply answers, as by his wife’s tone what was to follow would not be pleasant.

“He was killed at some place called Kokoda.” May’s voice lowers to a whisper.

“When?” Alf nervously asks, knowing Trevor was attached to the same regiment as Jim.

“She said some time last month but wasn’t clear on the day, the army is repatriating his body when they have a flight.”

“That would have happened after Jim penned his letter,” Alf acknowledges as Gavin arrives with his usual bluster and takes his seat at the table.

“Gavin how many times must I tell you?” May postures.

“What!”

“Your hands, you could grow spuds under those nails, go wash your hands.”

Gavin returns from washing as May places her large china teapot on the table beside a plate of sandwiches and remaining scones from the previous day’s baking, “and don’t you go scoffing into the scones Gavin or you won’t eat your dinner.”

As the teapot is placed it clinks against the sugar bowl. May concerns it has chipped but on inspection it remained sound. The teapot was her mother’s and one of the few items she inherited after her early demise.

“Wasn’t Trevor a mate of yours?” Alf asks Owen.

“More a rugby mate of Jim but I did know him.”

“Sad days,” Alf simply says.

“What about Trevor?” Gavin asks as he reaches for a second scone.

May gives a displeasing glance.

“I’m a growing boy,” Gavin excuses and reaches for the butter.

“Go lightly on the butter Gavin, there won’t be more until the next rationing.”

Alf explains Trevor’s passing and gives his youngest a contemptuous glance.

“What have I done now?” Gavin stresses knowing well his father’s many glances, as far as categorizing them into severity from mild displeasure to, shit I’m really in for it.

“I hope you have got rid of that silly idea of enlisting,” Alf says.

“Have to – they all know me around here but I’ll be sixteen soon and -,”

May cuts across her son’s answer, “and nothing young man, you have to be eighteen to enlist, besides you are needed on the farm, that is enough towards the war effort for you and you haven’t finished your schooling.”

“Schooling,” Gavin sarcastically repeats.

“Your father has high expectations towards your future.”

Gavin reaches for a tomato sandwich without reply.

“Did you hear me young man?” May follows her displeasure.

“Yea I heard.”

“Don’t use that tone towards your mother,” Alf’s pitch lowers towards his son’s insolence.

“Sorry mum.”

“Have you been given homework?” Alf asks Gavin.

“There is always homework.”

“Then as soon as you have had your sandwich and finished the watering, you better get on with it.”

“I have tomorrow and the whole weekend.”

“Yes and Monday is not so far, I don’t want you missing the bus again, while trying to finish homework instead of eating your breakfast.”

Another day and still the rains hold off. Some blamed the war saying with all the bombs being dropped around New Guinea and the Coral Sea, they chases the clouds away. Others with more intelligence realized it was the dry season and soon the monsoon would arrive from the north-west, as already the changing of the seasons could be felt in the air and daily thick black stratocumulus clouds hug the northern horizon.

Early morning found Gavin hand watering the lettuce planting and as he finished Owen calls to him while bringing the truck from the shed. “Hey kid, want to go into town?”

“I’ve work to do.”

“Dad said it would be okay, it is only for the morning and I can help you with your chores later this arvo’ if you like.”

“What are you going into town for?”

“I have to go to Jack and Newel and visit Sid Burrows, also mum wants to see if the material she ordered is in stock.”

“You’ll need to get a move on, Jebreen’s closes at noon on a Friday,” Gavin placed aside his watering buckets and approached. “Anyway I’ve finished with the lettuce and I would like to visit someone while you are at Sid’s place.”

“Who?”

“Just someone.”

Owen didn’t push further as Gavin climbed into the cabin, “do you want to drive?” Without question they change places, “but keep the speed down as you don’t want to blow-up the engine.”

“I don’t speed,” Gavin argues.

“You do, I’ve seen you when you do deliveries; as soon as you are out of the gate your foot hits the floor.”

“I do – don’t I?” Gavin laughs as he throws the old Bedford into gear.

“Once we’ve done the deliveries, I’ll take over when we reach the town sign,” Owen instructs.

After departing from the base and approaching the crossover of the rail line but a mile further on, the brothers discovered a number of soldiers blocking the road ahead and appeared to be searching vehicles as they travelled in both directions. By the soldiers arm bands they we military police and in Owen’s experience they were unforgiving with an air of superiority.

“Looks like problems, you better slow down,” Owen suggests.

“Slowing down,” Gavin agrees and grates the gears while bringing the truck to a crawl.

Ahead the soldiers at the barricade appear to be without urgency. Gavin continues slowing the truck towards the barrier and stops within inches of the closest soldier, who leisurely sidesteps before going towards the truck’s rear to scrutiny what they were carrying. Once satisfied he comes to the driver’s door but directs his question past Gavin towards Owen.

“Empty,” the soldier aridly says.

“We have just made a delivery to the base.”

“What were you delivering?”

Owen becomes bold, “three bags of carrots, four of spuds, some runner beans and -.”

“Where are you heading?” the soldier questions while ignoring Owen’s excess.

“Into town for supplies.”

“Were you trying to run me down?” the soldier says, this time directing his question towards Gavin.

“Neither brother responds.

“I know you but who is the kid?”

“He is my brother Gavin Parker.”

“He appears a little young to be driving?”

“He has special dispensation,” Owen says knowing it to be a lie but in such troubled times; many found it necessary with the older boy away fighting, for younger lads to become delivery drivers.

“Yea when there’s no one else about to do the driving sorta’ dispensation,” the soldier suggests.

“He needs the experience, is there some problem ahead?” Owen asks.

“You could say that.”

“What’s up?” Owen presses further from the soldier who ignores his request and approaches one of his companions. He remains in conversation for some minutes before returning to the truck’s passenger window.

Owen repeats his question.

“Just an incident is all you need to know but when you return home I would like you check your sheds.”

“What will I be looking for?”

“You will soon know if you find anything,”

“Anything?”

“I think you are smart enough to fill in the blanks, now off you go.”

Gary’s stories are about life for gay men in Australia’s past and present. Your emails to him are the only payment he receives. Email Gary to let him know you are reading: Conder 333 at Hotmail dot Com

17,423 views