Published: 28 Apr 2022

“Wallopers!”

The shrilled cry came from mid Russell Street and with the shout a running of lads, as officers from the nearby police station commenced to clear the area of petty criminals and pocket-dippers.

It was almost possible to smell the nervous tension as young men and boys scattered in all directions, some finding haven in the many dark lanes of the Little Lon and its notorious brothels, gambling houses and sly grog sellers.

The sound of tin whistles pierced the still afternoon air, accompanied by the dull bone crunching thud from well aimed truncheon, upon youthful heads. Cries of get the little buggers but alas, young legs are swifter than old and adrenaline pumps faster while being pursued. Besides those of the Little Lon were only to please to allow their premises to be used as refuge, so it would be through the front door, out the back and over the fence, to once again innocently mingle with the afternoon’s crowd of the Lon.

The top end of Lonsdale Street and that around Spring Street were dangerous places to be if a young lad had mischief on his mind, as it was known as the law precinct with its goal complex, city police and court house, all within spitting distance of each other. Book’em, break’em and bind’em was the jest, as it was but a short walk from police station to the court and on to prison and in those trouble times it didn’t take a great deal to be held at her majesties pleasure.

Even with its petty crime wave and economic downturn Melbourne did have some public entertainment, therefore being a sunny Saturday afternoon, many were making their way to Victoria Park, to enjoy a football match. It is the final game for the year and the seventeenth season of the Victorian Football Association, since the colony developed a game from that played by the natives, mixed with others codes from the British Isles and a few colonial interoperations added to the strange mix but the code quickly became a success, even as far as exporting it to other colonies.

In the beginning it was called Melbourne or Victorian rules and believed to have been played between two sets of large eucalyptus trees, a pair at each end of the Richmond cricket oval and played without a set number of players, or allotted time. It was said one game went for an entire week with players joining or leaving the game at will and during those not so halcyon days, it wasn’t uncommon to come away with a broken bone or blackened eyes.

Who do you barrack for was a constant question during the football season, the use of the word barrack believed to have come from playing the soldiers from the Victoria barracks, who were known as the Barrackers.

Many new chums to the colony disagreed with the oval shape of the ball, being even more elongated than that used in rugby and what of the four scoring posts, rather that the H design of rugby, or the netted goal of soccer and there wasn’t any offside rule to scream at the umpires as there is in rugby; the title of umpire coming from the game of cricket, while not using referee employed in English football. Even so it was Melbourne’s game and enjoyed by most, while further north in Sydney and Brisbane the preference was rugby, while describing the southern interpretation, with its high marking, to be nothing but aerial ballet, a game that ladies may enjoy playing, most defiantly not for real men.

The southern game may not have been as bone-crushing as Rugby or as fastidious as soccer but it did have many other skills, as the drop kick for goal, the long kick that with pinpoint accuracy would land the ball in a teammate’s grasp, not excluding the low pass that often brought the receiver to grief from a strong and dangerous tackle.

Eventually tripping was disallowed and in doing so gave the opposing team a free kick. Free kick umpie would lift with one voice from the grandstand at the slightest misdemeanor. Throwing the ball also became disallowed and the ball had to be punched from one hand with a closed fist on the other. Once you comprehended the many rules, you were ready to stand on the sideline and shout abuse at the umpire, calling him a maggot, being in reference to his white coat.

It was Collingwood’s first year in the newly formed league after branching away for an earlier club Britannia and on this day was to play Essendon Town, the Same-olds’. As Victoria Park oval was in the limits of Collingwood it would draw a good working class crowd but few believed the newly formed Magpies had any chance in winning against a well seasoned Essendon Town, if they did not, there would be havoc on the streets after the game, even more so if Collingwood happen to be surprisingly successful.

Sporting events were popular in depression plagued Melbourne and as the crowds gathered, so did pickpockets and others bent on crime, such as snake oil peddlers, selling bottles of questionable liquid to re-grow you hair, cure warts or regain potency in one’s dwindling romance. Young lads would beg by tugging at coattails, while their friends rumbled skillfully through pockets. A shilling or a few pennies would be enough to feed a family for a day or so, a gold sovereign for the week or more. A gold watch and chain would become bounty without question at the many pawn shops within the city, which were often nothing but fronts for criminal activity.

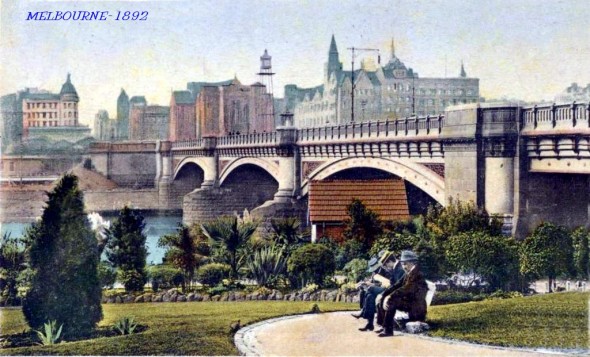

Melbourne; or Marvellous Melbourne as often titled, was the principal city of the colony of Victoria and before the downturn believed to have been the wealthiest city in the world, because of the rich gold fields of Ballaarat and Bendigo. Until now it had been growing in size and grandeur at an alarming rate, with close on half a million inhabitants, since its foundation a little more than fifty years earlier.

Even so its grandeur and golden past were not enough to prevent the world financial crash of the previous year. It appeared the Argentine had financial sniffles, the British banks caught a cold, while the world came down with fiscal flu. Financial greed in London invested so heavy in South America that it could not be supported and when a little earlier the London based Bearing Bank got the jitters and Rothschild’s bailed them, the world’s investment nerve took a nosedive.

Soon after the share market tumbled as there wasn’t any substance in real value and the money bubble bust. Many lost everything while in general it was the middle-class, those who were the pillars of financial wellbeing in any society who were financially hit the hardest but it was the lower class that suffered the most and for the longer period.

The six Australia colonies suffered worse than most as they relied heavily on British investment, so as that dried away, no amount of golden metal could waylay the developing trend. It was Victoria’s Melbourne that took the heaviest fall of all the antipathetic colonies. The downturn dissolved all confidence in being marvellous and in public the name of Bearbrass, as originally suggested for Melbourne’s identity, once again became a popular description of the depressed city, being reduced to the derogatory title of Bare-arse.

Melbourne may have grown from a scattering of tents in thirty-five to a world city of five hundred thousand in the eighties but now in the depressed nineties it suffered from stagnation and with the downturn would do so for a good decade to come. On the surface it remained a world city, with fine bluestone buildings reaching high into the smog-filled sky, its streets sounding to the noise of peddlers and hansom cabs, of drays bringing produce to the city but more than those were the carts taking away the mere belongings of the poor, evicted from their homes as unscrupulous landlords acted without compassion.

During those few short decades since foundation the city had also grown fast beyond its ability to deal with waste and in the main, kitchen and night waste, as well as that from business and farms, was emptied into drains that flowed into the street, then to the creeks and into the river that most said flowed upside down, being named Yarra from a native word for river of mist, or possibly where two rivers met, The Yarra-Yarra, depending on which tribe of natives was given accreditation.

Most houses had a small closet size edifice at the rear of the property called the pan closet, or as commonly referred the thunder-box or dunny. From a door at its rear the nightman would come weekly to empty the pans and take the contents away for use as farm fertilizer. If the collector was inclined towards laziness, the refuse would be dump beside some secluded roadside, or if no one was watching directly into the Yarra.

On cold and wet nights folk would use a chamber pot or with humorous tag the guzunder, as it goes-under the bed. Being indolent many would also empty it directly into the drains. So to any newcomer to Melbourne in those turbulent depressed years, the first thing that would be noticed would be the distinct smell of sewerage, giving Melbourne a less prestigious title, that being Smelbourne.

Near starvation was common in Marvellous Melbourne during the depressed nineties, mothers would do their best and go hungry to feed their children, possibly turn to prostitution. Children would steel and congregate in gangs of larrikins known as the push and men would go on the wallaby, a word for travelling the countryside while looking for work.

On any day a number of men would arrive at your farm door begging a shilling to cut a week’s worth of wood, or a feed to dig a ditch. These men became known as swagman, carrying with them little more than the clothes on their backs, a rolled blanket, a billycan to boil water for tea, if tea could be begged, a set of stained cutlery, a pot for the campfire and a head filled with dread towards an unknown future.

The swagman was usually a man of honor, as before the depression he may have managed a bank, owned a haberdashery, or toiled long and hard on the docks. Often he would be married with children but departed from home to lessen the pressure on the little food that could be afforded. In general he was resourceful and gave praise to he who introduced the European scourge of rabbits to the Victorian landscape, as without the rabbit now plaguing the country, cooking pots would hold but a few root vegetables, or native plants known to have questionable sustenance. Yet with their resourcefulness these men of the road, had failed to follow the ways of the aborigines and discover what bounty the land had to offer. Even when the traditional owners obliged to share their customs accumulated from more than fifty thousand years, on how to survive in such a harsh land.

Some on the land would show pity on the travelling swaggie, possibly supply a feed, some tea, sugar or tobacco, all given with apology that it could not be more, as in general those on the land were also suffering. Others would shun them at the gate, sool the dog onto them, or waste a scarce round of ammunition above their heads, or worse at their person. To those that treated them badly the swaggie had his way, a secrete mark on the gate post, or a notch on a close by tree giving warning to the next who chanced by, declaring there wasn’t any cheer to be had at such premises.

Although a number of these men were not so willing to work and were referred to as sundowners, as they arrived at sunset looking for a feed and somewhere to bed down, knowing there wasn’t enough hours of sunlight left in the day to work for their food. Such were soon given short-shift without honoring their need. In the most they were few but even so did give the swaggie adverse reputation.

“Where have you been?”

The issue was sternly directed as plates clattered upon table top.

Without answering the lad withdrew four large potatoes caked with the red soil of the nearby Gippsland from his pockets and placed them gently onto the table, he smiles broadly with anticipation for phrase towards his resourcefulness.

“Where did you get those?” The woman gratefully questioned giving the closest potato a gentle poke with a finger, while nervously waiting for her son’s reply, knowing if stolen it would be enough to earn a lad a lengthy visit to the bluestone edifice in Russell Street, or if it happened to be the first offence, a thrashing behind the local police station as a not so subtle warning.

“Got them,” the lad simply replied with a cheeky smirk, his green eyes twinkling away his obvious criminal activity.

“Again where have you been?”

“The game,”

“And where did you get the entry shilling young man?”

“No shilling, we simply caused a diversion and when the fella’ on the gate was distracted we bolted in. He almost caught Jonesy’.”

“One day Devon, one day; or you will be the death of me from worry and that is a certainty.”

The women returned to her single pot bubbling on the stove, giving it a gentle concerning stir, wishing it was more but thankful it was anything. Taking in washing paid little and that what her eldest brought home helped but only to keep them fed and the rent paid. She remembered better days with fine china on the table and a full larder. She then had a man to provide for her and the boys but chance had taken away two husbands, two fathers to her boys, leaving her destitute.

“Who won the game?” she asks as a distraction from what was lacking in her bubbling pot. It would fill their bellies but little else.

“Essendon Town,” Devon gave an obvious huff of dissatisfaction towards the game’s outcome.

“What was the final score?”

“Don’t ask,”

“Obviously you team didn’t do well,” his mother was teasing as she wiped away the perspiration from her brow with a dishcloth.

The lad ignored the suggestion, “there was strife in Smith Street after the game, upending carts and all. Also Millard’s corner shop had a broken window and that Chinaman’ who has the eatery on Mason had a dead cat thrown through his doorway,” a pause and a smile, “it will be in the stew-pot by tomorrow that is a certainty.”

“Poor Mrs. Millard and she being unwell,” Ilene sympathized while disregarding the treatment of Billy Wang and his dubious eatery.

“She’s well enough; you should have heard the cussing, I didn’t know a woman would know such words.”

“I hope you weren’t involved.”

The lad didn’t answer.

“Dinner is almost ready, go wake your brother or he will be late for his work and let him know he will have to wear the same shirt as I forgot to do his washing.”

Devon, or as most knew the lad, Dev, had an older half brother Jack by four year, who was fortunate to acquire work for David Mitchell at his brick factory on Burnley Street beside the Yarra river. His work was arranging brick at night for the following day’s delivery and odd jobs around the factory yard. It was heavy, dirty work and didn’t pay much but at least it put food on the family table.

David Mitchell was a local identity with a large family of whom Helen was the most prominent. Helen Porter Mitchell was an operatic soprano with a fine voice who changed her name to Nellie Melba and married a sugar mill manager in Queensland. Soon after she deserted him for fame on the European operatic stage and was believed to have slept her way through the crown heads of Europe. Nellie also had another claim to fame and that being the first woman to lay down her voice on an Edison wax cylinder.

As a footnote to Nellie’s character, although her name change was in honor of her city of birth, she appeared not to hold its people dearly. What should I sing for them? A rising young singer asked of Nellie as she readied to travel to Melbourne for a concert engagement. Sing them any shit, Nellie is believed to have suggested; they wouldn’t know the difference.

Nellie’s marriage was failing from the start as both were strong willed, Charles Armstrong was the son of Irish aristocracy and his father the first Baronet of Gallen Priory, while Kangaroo Charlie, as Armstrong was commonly known was sent, as was rumored, in disgrace to Australia as a remittance man.

Armstrong loved the rough living of the outdoors and for a while was a station hand in Queensland. After marrying Nellie he managed a sugar mill in Mackay in that colony’s north but Nellie wasn’t cut out for the mundane, so she travelled to Europe to further her career. Armstrong followed and it became a battle of wits, with Charles failing to reinstate their marriage, so they divorced in America and he went to live in Canada and as Nellie climbed higher through the operatic social ranks, Charles was soon lost to history.

Devon Gooding at eighteen and a little more as he was quick to correct, was what was commonly known as a larrikin and member of a local push, The push being a gang of mostly late teenage lads with nothing to do but mischief and petty thievery. It was said of Melbourne that it had more larrikins to the square mile than any other city. They loitered around street corners and alleyways looking for someone to tumble, or an unattended store or street seller, where with the skill of a magician, they would strike and be gone into the crowd before the proprietor could take a breath.

At the time a visitor to Melbourne wrote in his journal, the street kid may be found on any city corner after dark, spitting chewing tobacco across the pavements while loudly cursing at anyone who chanced to pass his way. In the most it could be said of these lads they were thin, undernourished, badly dressed but wiry and most energetic and when being pursued they had the speed of a greyhound.

Dev wasn’t naturally evil, nor was he violent, or possess a bent towards criminal activity but soon realized if he couldn’t find honest work than it became necessary to pilfer to survive. His older brother Jack was to their mother’s first marriage, an American sailor who jumped ship during the Ballaarat gold rush, remaining in the colony long enough to marry Ilene Gooding and produce a son. Soon after Jack’s birth his father Jim Osmond joined the crew of a ship leaving for California and was never again heard from.

The Gooding home in Little Victoria Street was but a worker’s cottage consisting of one main room with an adobe floor, a bedroom and a second room not much larger than what could take a single bed and small cupboard for clothing. The boys shared the small room and when children also the bed top to tail. With Jack now working nights the bed was in shifts with Jack returning before dawn to throw his younger brother from his comfort. Sometime with much physical force, as there appeared to be little love between the siblings but if there was animosity between the brothers, it was but superficial as the love from their mother soon soothed away most grievances.

Dev pushed open the bedroom door with force. The door swings hitting the wall before quickly returning, almost catching him on the face. He softly curses.

“I heard that young man,” Ilene warns.

“Hey Jack your dinner’s on the table, mum said you better not be late for work again.”

“Fuck-off;” Jack growls and rolls away from the intrusion. He forces out a loud fart, “cop that.”

“Fuck yourself,”

“I’ll get you – you little -,”

Jack received the door slammed in his face as he jumped from the bed to inflict retaliation.

“That will be enough of that gutter language,” Ilene called from setting the dinner table.

“He started it,” Dev complains while placing the table between himself and his brother, they jockey from one side of the table to the other to gain advantage.

“And I’ll finish it, you little -,”

“Jack, try and be nice to your brother.”

“He’s no brother – it’s a weed.”

Jack noticed the potatoes on the table.

“Has the little weed been pilfering again?”

“Someone has to feed your winging gut,”

“Mum can’t you drown the little weed? You should have given him to the Didicoys at birth.”

“Both of you shut it,”

During their meal there was a knock to the door, “I’ll get it,” Dev offered being the closer.

“Crawler,” Jack softly accuses.

“Sit down and finish your meal, it will be Mrs. Simpson from the big house at the corner with washing.” As Ilene went for the door she commented to Jack; “best you get a move on, you don’t want to be late for work again.”

“I’ve got time, besides the night foreman is always late so he won’t see me arrive,” Jack assures.

With her arms full of washing Ilene went to the back and the washhouse.

“I’ll be off then,” Jack says, pushing his empty plate aside. As he passes Dev, he gives him a hard clip across the back of his head.

“Fuck off,” Dev growls.

“Another thing weed, I don’t want to come home in the morning and find the sheets stiff and sticky.”

“I don’t,”

“You do you little convict sod,” Jack whispers close by Dev’s ear, then gives the ear a twisting for good measure.

“That hurts,” Dev growls as he pushes Jack’s hand away.

Another clip to the back of Dev’s head and Jack departs as he hears Ilene returning from her washing.

“It’s hot,” she admits and wipes away the perspiration from the copper’s steam, “has Jack gone?”

“Just then.”

Ilene commences to clear the table.

“What’s on your mind Devon?” she asks, as by Dev’s expression he was pondering over some miniscule problem.

“Mum,” Dev says, his tone questioning.

“Yes dear,”

“Who was dad?”

“Your father was William Gooding from Sydney and your grandfather was from Henry Gooding from Devon in England. Why do you ask?”

“Is that why I’m called Devon,”

“Your father named you but you already know that.”

Dev was obviously thinking.

“What is on your mind love?”

“Jack reckons I’m a convict.”

Ilene laughs as she fills a pale with hot water from the stove for the night’s dishes. Using the vegetable grater she grates a small amount from a long bar of sunlight soap, the flakes gently sink through the water. Then with a large wooden spoon she froths the water.

“Your granddad on your father’s side was a convict but on my side they were all free settlers, they came out back in thirty-eight and I was born in Launceston in Van Diemen’s Land soon after,” she says while testing the temperature with her hand; “too hot,” she quietly states and adds a little cold water.

“Van Diemen’s Land?” the lad questions.

“As it was called then, it is Tasmania now. Your grandparents on my side came here when gold was discovered.”

“What did granddad Gooding do to be sent out as a convict?”

“Stole something I should think?”

“What did he pinch?”

“Your father never said but I believe his family was very poor, possibly it was a little food or some clothing but if the value was more than a few shillings it was obligatory hanging in those days, although in most accounts the sentence would become that of permanent transportation to the colonies, for most crimes excepting murder and treason.”

“Obligatory?” Dev questions.

“Yes without recourse,”

“What about dad, as the son of a convict was he also a convict?”

“No, your father was a freeman and your grandfather came out on the same convict ship as Flash Jim.”

“Flash Jim?” Dev says.

“Yes James Vaux, he wrote a dictionary on Australian English way back in twenty-two.”

“Did Grandfather live in Melbourne?”

“No he lived in Parramatta near Sydney as Melbourne was settled until much later.”

Dev appeared confused.

“Never mind love, James Vaux was quite famous back in those days and your grandfather was a chum of his while on the ship and they worked together for a time after arriving.”

“If granddad was a convict does that make me a convict?”

“Of course not dear, don’t listen to your brother.”

“How did dad die?” Dev asks. He already knew the basics but often questioned to reaffirm his own existence and the divide between himself and Jack, they being half brothers.

“Your father worked on the docks down at Port Melbourne and had a fall.”

Ilene’s thoughts digressed to that unfortunate day. It had been spring and coming out of a dreadfully wet winter but there was hope in the air and with a growing city there was much work to be had. Dev was just a little past his third year and Jack but six. William Gooding had been a handsome man of strong character and popularity but popularity alone could not keep a man safe, while work ethics on the docks regarded dockhands as expendable. Ilene’s passion flooded like waves of bitter brine on a distant shore. As they ebbed she shook them away with a deep breath.

“What about Jack’s father?” Dev followed hoping to acquire something derogatory to use against his brother.

“Enough of the past,”

“I only ask,”

“You sometime ask too many questions,”

The neighbor’s dog barks as Jack arrives home tied and cranky from his nightshift. The noise he creates while travelling the three steps or so from the gate to the front door sent the dog into frenzy.

“Shut it you mongrel,” Jack growled and teases the animal with his boot through the slats in the side fence by kicking at the palings. The dog flew at the fence, its snout through a gap displaying a row of snarling teeth. Jack laughed and left the dog to its continuing disquiet as the neighbour calls it back inside.

Ilene hearing the commotion made comment as Jack entered, “one day Jack, that dog will come right through that fence and have your leg off.”

Jack gives a disregarding huff, “one day I’ll boot it in the gob and it won’t have teeth to do anything.”

“I have some fresh bread would you like some breakfast before bed?”

“No thank you mum, Sid Topper gave me a sandwich as I was leaving work and my gut’s playing up from it; I think the flaming mutton was off.”

“Dev’s not out of bed yet,” Ilene says as she commences her first washing load for the day.

“He soon will be.”

Jack enters into the bedroom and removing his boots allows them to fall heavily to the floor, “Right kid off cock, on socks,” he says while giving Dev a rough shake.

Dev wakens in fright.

“You back already?” he growls.

“Get out of bed kid I’ve had a rough night and need my sleep.”

“I was dreaming,” Dev says with a yawn.

“Something devious I should think,”

“No I was lost out past Hays Paddock and a mob on blacks found me but when I asked where I was and how to get home, they spoke in language and laughed at me. Do you think dreams mean anything?”

“Wouldn’t know but Wayne Langton says his local priest can interpret dreams. “He’s Catholic,”

“Catholic, Proddy they are all the same, now move it I need some sleep.”

Jack strips down to his long-johns underwear displaying a large rent at the front.

“Your little worm is showing,” Dev laughs.

“It’s bigger than yours, come on out of bed.”

Dev reluctantly leaves the bed and pulls on his trousers.

“I hope you haven’t soiled the sheets again you little sod.”

“You didn’t mind using me when it suited,” Dev retaliates while keeping his distance.

“Aw fuck off or I’ll do you again.”

“I’ll tell mum,”

“Go ahead she won’t believe you.”

“She will,”

“Go on I dare you,”

Dev closed the door.

“What are you going to tell me?” Ilene asks.

“Nothing, I was only teasing Jack,”

“You shouldn’t annoy your brother,” Ilene warns with a wry smile, knowing her words would be wasted on her sons, as they were like two roosters in the same henhouse jostling for advantage. Even so there was a measure of love between the boys. They may curse the other’s existence with cruel words and the occasional almost sadistic retribution from Jack upon Devon’s person but never to any measure of harm. A so called Chinese-burn, a clip to the head or arm twisted behind the back, until close to joint dislocation would be the most. You don’t like that do you? Jack would growl close to his brother’s ear but Dev would hold his breath and his silence, never admitting to the pain but in many ways their love, although somewhat subtle, did subsist.

“I hear there is work offering at Warrendyte on some tunnel,” Ilene suggests as Dev comes from his shared room to greet the early morning.

“Who says?”

“Mrs. Scott up at the corner, I was talking to her on the way to the shops, she heard it from the rag and bone man, who had been collecting from the bins up behind Parliament House. He heard it there while eavesdropping on a group of members.”

“What would he know?”

“That I can’t say,” Ilene admits.

“It won’t happen,” Dev assures.

“And why not young man?”

“It was only a suggestion, I heard so down in Spring Street Yesterday.”

“What were you doing in Spring Street?” Ilene questions.

“Probably thieving,” Jack calls loudly through the closed door from his bed.

Dev ignores his brother’s insult. “I was with some mates.”

“What mates would that be?”

“Jonesy’ and others,”

“I haven’t seen Douglas for a while how is his father?”

“He doesn’t say much and it’s best not to ask but from what he doesn’t say, I would think nothing has changed.”

“No nothing ever does with that man.” Ilene says. She had a soft spot for young Douglas and if she had room, or could afford so, she would have him live with her but knowing his father, such a suggestion would be met with outrage.

During the previous afternoon while those of the Smith-street push were applying their illicit skill in Lonsdale Street and before being set upon by the establishment, Dev and Douglas Jones were casing the coffee houses along Spring Street, where members of the Colonial Assembly congregated to discuss strategy for the pending election, away from prying ears of Government Opposition.

It was William Beazley the member for Collingwood and known by sight to Dev, who loudly down played using the tunnel as expensive and seeing his party only held a majority of one in the Council chamber and two seats were up for election that year, it was best to shelve the idea as it was thought to be unpopular.

Dev and his mate Jones came away with empty pockets as the disturbance in Lonsdale Street made those in the coffee houses aware of something being amiss therefore reminding them to be cautious and guard their valuables. As for the Warrendyte tunnel, it had been a project many years earlier to divert the Yarra River through a tunnel at Pond Bend so they could mine a three mile section of riverbed for alluvial gold. Although a small tunnel was successfully driven through solid rock across a distance of but twenty yards, the project was a failure, now it was suggested the tunnel could be used to generate hydro electricity but again the cost was considered high for the electric power generated and a waste of the little money left in treasury.

“What were you doing in Spring Street?” Ilene again asks in a low almost accusing tone.

“Only passing,” Dev assures with a suggestive grin.

“I hear there was some disturbance?”

“It wasn’t us.”

“It appears it is never you Devon,”

Although Ilene never mentioned so, she knew her son was part of the Smith-street push as she had seen him congregate and had heard many voices in opposition to their behavior from neighbours. Ilene also realized without Dev’s illicit pittance they would more often than could be counted go hungry, as her washing and Jack’s wages were far from enough and Jack’s heavy work needed more than a few potatoes to keep up his strength.

Ilene wasn’t a religious woman as she had seen too much hardship to believe, beside an hour at church on Sunday would take away the completion of a load of washing. She had lost two husbands, one through desertion another from a fall, to hold onto faith and how could god or Jesus leave her children without a father for guidance, her without a man to provide. Then again the city’s torment was obvious, as street by street the depression widened and she had seen too many god fearing men and women become destitute, forced from their homes with little but what they were wearing. She looked upon Dev as he sat at the table picking at the newsprint pages place as a tablecloth and hoped if there was a god he would not allow her family to suffer in the same way as others.

“Have you tried to find work?” she quietly asks.

“I have,”

“Where?”

“All over, even at the brickworks where Jack works but nothing, most of the time it is bugger-off.”

“You do your best I’m sure.”

“One’s best isn’t good enough anymore,” the lad contradicts.

Collingwood and adjoining Fitzroy were considered to be slums and well avoided by anyone of breeding, or with coin in pocket. It was also spoken of in Parliament but instead of relief for the suffering, avoidance of such areas was best observed. Besides the colony’s coffers were almost empty and the downturn was general across the city, across the colony across the continent across the world. Collingwood like elsewhere would have to pull itself out of depression by its own means.

If a visitor came to Melbourne in that year and cast his eyes about, while disregarding the mood and depressed state of the people, he would not realize the paramount of the situation. All about structures were growing taller and bolder and the bleakness of bluestone edifices still lifted from the soil to house government offices, or the clergy at an increasing rate. Even the new Saint Paul’s Anglican cathedral was towards completion on its site as gateway across the Yarra to the south, although its spires were being deferred to a future time. Also Saint Patrick’s catholic cathedral grew taller by the week growing up from its prized position on the higher ground behind the Parliament building.

There was humor to be had regarding the catholic cathedral as the Parliament building was on Spring Street at the top of Bourke Street and the cathedral on the higher land directly behind. It was said the Catholics liked the high ground to be closer to heaven but the parliament was to the front. Once completed Saint Patrick’s spires would stretch far above the parliament, so the city fathers decided to erect a dome on the parliament to block out the spires but along came the depression and the dome was never built. Now if traveling along Bourke Street in an easterly direction it appeared that the Parliament had slender Gothic spires protruding from its heavy Victorian grandeur.

Much of the government work in the city was created to give a little relief to the multitude of unemployed but wages were meager and the work hard and dangerous if even obtainable. There would be a hundred lined for each position offered and it would be first to arrive successful. Daily unemployed men would be found walking the streets asking anyone in business for even an hour’s work, doing anything from sweeping the shop floor, to carting product but disappointment was the main, lending to the high suicide rate amongst young men, who should have been the backbone of a developing colony. Even so it was in the country that suicide numbers were highest, as crops failed or banks foreclosed on loans.

At the docks the situation was even tighter, as most of the work was casual on the arrival or departure of a ship. When men were required a handful of paper scripts would be flung into the waiting crowd and those lucky to catch the flurry would be hired. Fists would fly, knives produced with the melee becoming a distraction and entertainment for those in authority.

Ilene had a cousin who lived far away in country Ararat, a small town far to the west of Melbourne, founded on gold but surviving on wool. Lucy had offered accommodation for Ilene and her sons but that was long ago before the downturn, not long after the death of Devon’s father. Now even to write to her cousin would be a strain on her existence, the penny postage could be spent on part of a meal, besides Parliament was thinking of returning to tuppence as it had been before the downturn. Also there was the travelling, Ararat was at much distance and a coach ride, or train ticket for her and her two boys was beyond her means and walking beyond consideration. Therefore the bind she was living appeared to be ongoing and permanent.

Although Ilene had no love for country living, she often thought of her sons running free in clean country air, learning to ride horses and swimming in water untainted by sewerage and factory waste. It would be a happy life where enough vegetables could be grown to feed many, sheep to put mutton daily on the table but could she abide Lucy’s continuous criticism of her lack of religion and interference in how she should bring up her sons. Could Devon and Jack learn to live with Lucy’s three with their spoiled attitudes.

“There are two pennies in the jar could you get some potatoes for tonight’s dinner,” Ilene mentioned as she thought of what could be add to the pot. “Some onions would be nice,” she continued and remembered better days of lamb roast and pudding made with eggs, with fresh butter on their bread instead of almost rancid lard.

“Dev collects the coins but knows where he can get a few potatoes for nothing. He secretly replaces the coins as they could go towards something else for the pot.”

“I’ll be off then,” Dev says as he collects his scally cap from the sideboard and sits it boldly on his head, his hair protruding about the cap’s rim like dark straw on a scarecrow’s head.

Ilene softly laughs towards his bravado.

Dev gives his broadest smile and pushes his cap further back on his head almost to tipping.

“Will you be seeing Douglas?” Ilene asks.

“Possibly,”

“If you do then invite him back for dinner,”

“Will there be enough?”

“Yes we will make do and don’t be too late as I’ll need you to deliver washing to Mrs. Ryan over in Bedford Street.”

“I won’t be late,”

“And mind you behave yourself;” Ilene warns. ‘Such a handsome lad,’ she thinks, remembering her second husband and his gentle ways. At eighteen Devon was his image and to look upon Devon brought fond memories giving her cheer as well as sadness.

“Don’t I always?”

Ilene worries, she knows Dev’s intention and with the evening there would be onions but can only hope her son is safe.

Gary’s stories are about life for gay men in Australia’s past and present. Your emails to him are the only payment he receives. Email Gary to let him know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net

18,678 views