A sequel to 1813

Published: 19 Nov 2020

Prologue

“There is gold in the south and folk are picking it up like pebbles from a beach.”

Those words excited two young men living almost normal country lives, all be it with a secrete they could not share, in the vast sheep lands beyond the Blue Mountains of New South Wales.

Although stricken with the dream of golden riches, once on those southern gold fields the boys found they weren’t cut out to dig and pan for the elusive colour, yet they soon became part of the rich tapestry of the goldfields but didn’t bargain becoming involved with a miner’s rebellion.

Chapter 1

The cry had come from far to the south and was strong within the colony of New South Wales. At first it was but a murmur then it became a flood of adrenalin as the population of Sydney emptied onto ships, or trekked the six hundred mile or more for the renegade colony of Port Phillip an illegal settlement. With revised penal laws relating to fewer convicts for transportation, Britain was loosing the will to increase further development of the southern continent, or expand further her far reaching empire, which year by year was becoming a logistical problem of some magnitude.

Eventually it was deemed necessary to appoint an administrator to bring law to the developing settlement of Port Phillip, done so by appointing Charles La Trobe to the position of Superintendent under control and guidance of Governor George Gipps in Sydney but without representation in Britain or Sydney.

After the discovery of gold and the influx of tens of thousands to Port Phillip and the extensive goldfields beyond, the voice from the south had gained enough strength for the district to be considered a separate identity. With the increase in population and continuous protesting, the Port Phillip district was given the right to elect six members to the New South Wales Legislative council.

The city fathers were so incensed about the act; they instead elected Lord Melbourne the former British Prime Minister and Home Secretary to the position. Needless to say Lord Melbourne never arrived to take up his position, although by all accounts he was somewhat humoured by the suggestion and said as much on the floor of the Commons, to the cries from the opposition for him to do so with their blessing and as soon as it was conceivably possible.

After continued protest Port Phillip was rewarded separation from its northern neighbour in 1851 and given the title of Victoria in honour to the new queen, while its principle settlement was named Melbourne in honour of Lord Melbourne. Immediately the district began to flourish and soon outgrew Sydney but with the discovery of gold Melbourne now played second fiddle to Ballarat and the goldfields.

Some few years earlier, two adventurers in the guise of John Batman and John Pascoe Fawkner, true rivals in every sense but with the same resolve, sailed separately from Van Diemen’s Land, crossing Bass Strait while looking for new pastures for their ever increasing sheep flocks, eventually settling on the banks of a river at the head of the bay.

There had been an earlier attempt to settle the large bay some thirty years previously, as at the time it was believed the French were interested in the southern coast but that attempt was poorly organised and failed and the inhabitants of more than five hundred, mostly convicts, were shortly after removed to the new settlement of Hobart Town in southern Van Diemen’s Land.

Some years later in May 1835 John Batman arrived at the head of Port Phillip and made a suspect, if not totally illegal purchase, of six hundred thousand acres of well watered grazing land from the local natives. Batman also brought with him a document of purchase, drawn up by a legal acquaintance for that purpose.

After meeting with a number of elders of the Wurundjeri people, Batman had them place their thumb mark on his so called bill of sale, the price being an assortment of blankets, axes, scissors and other trinkets that in general only mesmerized the natives while in the most having little practical use.

In retrospect Batman’s offer was more than likely accepted by the natives as gifts rather than payment for most of their homelands. It was also doubtful if those who placed their thumbprint to the document had authority of ownership, seeing that in native tradition ownership was not singular but collective.

As for the bill of purchase it would have never been upheld under British law as the natives didn’t understand what it was they were signing and Batman had already had his application for land in the Port Phillip area rejected by Governor Bourke back in Sydney, under direction there was to be no more settlements outside New South Wales and Hobart, which in purpose was but a prison for the worse behaved convicts.

After the dodgy business with the Wurundjeri elders had been executed, John Batman sailed back to Launceston and quickly returned with his flock, only to discover his rival John Pascoe Fawkner was already ensconced on his claim. The two soon argued over who had rights to the land. Batman produced his document, and Fawkner declared it invalid while the natives stood aside bewildered by the developing fracas, then instead of an all out battle of wits, they agreed to settle on the banks of the Yarra and attempt to get along together but from then on it was nothing but an uneasy truce.

This is the place for a village, was alleged to have been John Batman’s words as his axe struck the first blow on native soil. That simple axe blow would soon reverberate around the world bringing a flood of land and gold hungry migrants without taking notice of the embargo placed on anyone settling in that part of New South Wales.

The settlement soon grew from a few tents and assortment of daub and wattle huts in 1835 to a population of seventy thousand in 1845, to over two hundred thousand with the discovery of gold in the spring of 1851. Those sixteen short years had transformed tranquil native hunting grounds into and extension of Europe.

Gold was that cry, they have found gold in Port Phillip and it is there for the picking, laying about on the ground and in pounds not ounces. All one has to do is kick the ground and it comes up yellow.

True, gold had been found in quantity at Bathurst west of the Blue Mountains and Sydney in February of that year but the alluvial was quickly worked out and to access the yellow wealth one had to dig much deeper, while only the lucky and those prepared to break their backs struck the elusive yellow metal. Most dug deep and found nothing. Now it was late August with the new spring in the air as the cry came even louder from the south.

The cry was loud across the mountain barrier from Sydney, where shepherd and labourer down their tools and crooks and took to the road, leaving the growing flocks of sheep unattended in the hands of the squatter, who in many instances relied on the knowledge of his shepherds and lacked the will or ken to perform manual labour for themselves.

Many such landholders came from middleclass London, or were the second sons from county estates. They were men with soft hands, adventure in their hearts, with money in their pockets and time honoured influence in the halls of government. Such men became landowners on the far side of the world in possession of land they had never seen, or idea how to make prosperous. They were given parcels of territory by parliamentary decree, arriving with demand upon the colonial government to honour such grants. Sometimes more than one claimant would declare ownership to the same grant.

The cry was also heard as far away as California, to where over the previous decade a large number had departed from New South Wales, many being escaped convicts. New South Wales had been in most an open prison, relying on leg irons and the fear of the unknown beyond the narrow coastal strip and the less settled area just beyond the barrier of mountains to contain their charge.

Now those who left for California were returning with renewed yellow-fever. Not to say California wasn’t please with their departure and in most because of the antics of a gang known as the Sydney Ducks, a well renowned antipodean gang of thieves and arsons, who continuously caused havoc on the Californian goldfields. Often their members were restrained and marched down to the docks, with a suggestive rope around their necks, then handed over to the next ship sailing south.

Also the cry was heard in the orient with Australia becoming known as Xin-Gam-Saan, being loosely translated as new Gold Mountain with California having the title of Gam-Saan. Asians came in groups, sent by their village, or some devious organization of triads that owned right to most of what they found and their souls. Others came as coolies to work as cheap labour after the abolition of transportation from the motherland to New South Wales.

It was one such returnee Edward Hargraves who had previously travelled to California to make his fortune and noticing the terrain there was similar to what he remembered in New South Wales, decided to return south and try his luck. Soon after returning he discovered gold near Bathurst thus reversing the haemorrhaging of settlers from New South Wales across the Pacific.

It was after the discovery of gold at Bathurst the founding fathers of Port Phillip issued a reward for the discovery of gold in Victoria, as like before in the north to California, Port Phillip was now loosing its population back to New South Wales.

With convict transportation at an end in New South Wales for more than a decade, paid labour was hard come-by and wages grew at such a rate they soon outreached profit. With flocks unattended they wandered aimlessly, bands of aborigines came to realise sheep were easy pickings, being thought of as free gifts from the invading white man. After doing so it was common place for the settlers to retaliate against the natives, often brutally by killing women and children, sometimes it was poison or a black hunt when they would be run down as sport by dogs, or shot in their camp while they slept.

Such behaviour was not part of the Elsie Downs attitude. From its conception Hamish and Edward sympathised with the natives and in their way paid for the use of tribal hunting land by offering the occasional sheep, or bullock and other supplies, while allowing the natives passage at will. Even during the tribal wars against the cattlemen to the north those on Elsie Downs was spared from black insurgency because of their empathy.

Elsie Downs on the banks of the Fish River was less influenced by the downturn in labour as it was in most a family affair, although its closest settlement, Bridge Town, had depleted from three hundred souls to but half that number in under a month. Even the resident vicar, Eric Kidd, discarded his collar and headed south; leaving his wife and three children stranded under promise he would return a rich man.

Elsie Downs was well stocked and well run and had grown fivefold since its conception, remaining with the families of Buckley and McGregor, although Edward Buckley, who had no inclination towards siring progeny, left the running of the estate to the sons of his once trusted and much respected business partner. Unfortunately Hamish McGregor had succumb to typhoid after visiting Sydney some years earlier, providentially by the time of his passing his sons were advanced enough in years to take on the responsibility and did so without challenge.

There were three McGregor boys, two born shortly after the foundation of Elsie Downs in the guise of Hamish the oldest and Edward, who not to be confused with their Uncle Edward was mostly referred to as Ned, while the last Logan born ten years later with the death of their mother Elsie while giving him life. Her kindness was unknown to the lad although his brothers were not backward in reminding him of the event.

Ned the middle brother was much closer to the young Logan but Hamish was somewhat stiff and being the first born believed he had greater entitlement to their mother’s love than his brothers, while holding Logan’s very birth responsible for taking their mother from him.

There had been many challenges for the Downs over the years, not in the least the fire of thirty-six that destroyed both of the houses, only to be rebuilt in grand estate, becoming the finest west of the mountains and south of Bathurst. Another was the accident that took James Hill, Edward Buckley’s life’s love, from him after a fall from a horse while droving sheep to market.

James survived his fall but broke his back, only to die some days later in dreadful agony. Edward remained at James side during the ordeal, neither eating nor sleeping and when James’ final breath was taken it was Edward who closed his eyes to the world, allowing a single tear drop to fall on the now silent lips. Edward wiped it away and left the room. It was then he stood back from the estate and all but passed it on to the McGregor boys.

By the time gold was eventually discovered near Bathurst, that what was found many years earlier on Elsie Down’s had long been worked out but not before making the Estate most wealthy. During the year the gold ran out on Elsie Downs, William Buckley, Edward’s younger brother, had forgone his partnership while wishing a sea-change. With the help from both Hamish and Edward he was awarded a fair share of profit, while taking his adventure to the northern tropical coast and was never again heard of. It was believed he purchased a trading sloop from the district of Morton Bay and sailed to the islands, where he met his demise at the hands of cannabis somewhere in the New Hebrides.

It was a hot late summer’s day, finding Edward comfortably seated on the long gallery verandah at the rear of the house, beside him a cooling bottle of beer. That position at the verandah’s end was his favourite as it looked out towards a stand of acacia trees and the small plot set aside as the family cemetery.

‘We will soon need to increase its size,’ Edward though of his own mortality while remembering long gone days of hardship and eventual success. While in recline he felt a sense of comfortable as memories of happier days lined up within his thoughts but remorse for those who had gone on ahead leaving many fond memories.

Even now Edward could picture James as if his image had been burnt deeply in memory. He could clearly imagine James’ smiling face, smell his scent. So matched were their natures he could not remember a single argument between and when there was disagreement on some matter, it would be concluded with a laugh and that is your opinion so I respect it.

Edward wasn’t considered old but felt each one of his fifty-seven years weighing heavily on his heart. Finding he no longer belonged to the brave new country, or had desire to continue the empire he and Hamish McGregor had created.

Edward once had clarity of future and was stoic towards any goal. Most of which came to fruition but after James then Hamish, he lost the clarity and any will towards what had seemed to be a speck of light at the end of a long dark tunnel, always distant, yet always reachable. The pinhole of light had now faded and extinguished.

“They have all gone,” he softly sighed while his gaze fell upon the shimmering marble stone marking the grave of his life’s friend James.

“All gone Hamish, Elsie, Sam – even you Bahloo,” he included his long departed aboriginal friend, whose body had been wrapped in bark and placed in his favourite tree some distance along the river to be with his wind spirits. Edward laughed. “Wind spirits,” he softly mentioned. When things went well it was those spirits, if problems arose it was some dark earth spirit that caused it so and until his death Bahloo feared the Bunyip and its malicious ways. It would lurk in swamps and muddy pools waiting for someone to pass but never in the river. Edward believed Bahloo had selective convictions, as the river was much too important for native life to hold evil.

How small Bahloo had appeared in death. Anyone would have believed he was but a youth, yet he had the heart of a hero and the strength of two and loyalty that could never be questioned.

When there was nothing remaining of Bahloo but bleached bones and the tree holding them became damaged in a storm, Edward placed the bones under the ground within the acacia stand where Bahloo had made his camp, while refusing to live in the house. In doing so he had crafted a box from that very tree to protect him for the earth spirits.

Edward wished to cry but like his friends the tears had also gone, only the longing for their company remained, which daily seemed to sap a little more of his life’s force, giving wanting to be with them. He wasn’t a religious man but some part of him hoped, if nothing else, there was some meeting place where they would all be united. Some place where he would once again view James’ smile, smell his scent and hear his laughter.

Edward released a long sigh.

His thoughts were interrupted.

“Do you mind if I join you?”

“Logan by all means, I enjoy your company,” Edward pointed to the vacant chair, “put the book on the table but don’t lose my page, use that gumleaf as a marker.”

“What are you reading,” Logan asked as he collected the book and read its title, “the Gallic Wars,” he read the title aloud.

“It’s the works of Gaius Julies Caesar on the Gallic Wars,”

“You always liked history.”

“That I have,”

“We learned about Caesar at school, some joker stabbed him dead.” Logan remembered an oration from his school reader, ‘friends, Romans and countrymen, lend me your ears, I have come to bury Caesar not to praise him,’ he brought it to mind but had long forgotten what followed, as it had been much too dramatic and ponderous to retain a place in perpetuity.

“It was his friend Brutus and others, you can learn a lot from history, although most don’t and repeat the same mistakes again and again, that is the human way – but enough of that.”

“I brought you a fresh bottle,” Logan passed the beer to Edward.

“Where is Hamish?” Edward asked.

“Down at the woolshed with Ned, he should be up presently but Hamish is in a bit of a mood, some of the sheep got into the vegetable garden.

“Did they do much damage?”

“No he caught them before they had the opportunity but he is spreading the blame.”

“What’s on you mind young Logan, you appear somewhat troubled.”

“It’s Hamish he’s always on my back.”

“He means well and feels responsible for you since the passing of your father and dear mother,” Edward assured.

“What was mother like?” It was a question Logan often asked but was never absolute with the answer, besides the asking brought a little of Elsie’s spirit to mingle with his own.

“Elsie was a wonderful woman and most handsome, if handsome can be used to described a woman. No she was beautiful and had a gentle way with folk and a smile that could warm the coldest heart,” Edward assured and stood from his seat to lean against the verandah railing, “bloody hot ay’ mate,” he exclaimed in an attempt to draw Logan away from the past and what appeared to be a developing melancholy.

“Tis so,”

“The river is down for this time of the year,” Edward said and turned back towards the lad, “your father loved your mother dearly but never thought for a moment your birth was anything but a marvel and he loved you as much as he did Hamish and Ned, so don’t allow your brothers to convince you otherwise.”

“I realise that to be so,”

“How old are you now lad?”

“A whisker off twenty,”

“Ah, and not a whisker to show for it,” Edward laughed as the lad rubbed the fuzz on his chin in response to Edward’s suggestion.

“You miss him don’t you Uncle Edward?” Logan asked, following Edward’s gaze towards the marble stone describing the love of one man for another.

“I miss them all lad.”

“But mostly James.”

“Yes, mostly James.”

Edward turned from the cemetery while feeling a measure of pride in hearing a son of Hamish refer to him as uncle, also the lad’s acceptance that Edward could love a man and not a woman but equally as well. It was true all sons of Hamish McGregor accepted Edward’s life’s choice but more so young Logan and with that acceptance came wonder if the lad had leanings in that direction but it was never mentioned. As for young Hamish he appeared to have reservations on the matter as there was an obvious inner current of disapproval, surfacing in his continuous attack on Logan’s soft character.

“Father never spoke of how he came to New South Wales,” Logan said, his tone appearing eager for information that his brothers appeared reluctant to share with him.

“They were hard time Logan and you father was a good honest man don’t you ever forget it.”

“That was never in doubt, only Hamish refuses to speak of dad’s past with me.”

“I can’t see why it was never a secret and it could be said more that half those in the colony share the same beginning.”

“Hamish said he was a convict,” Logan suggested.

“He was lad, as was I but his was for the crime of attempting to survive, not of greed.”

“What did he do?”

“As I said he stole to survive as many did back then, nothing more.”

“Did you also?”

“No my crime was for love but enough of that. It is a time long gone and you should be thinking of the future and what opportunities this country can offer and not dwelling in the past.”

Even with such advice it was obvious the lad was not satisfied and wished to continue but understanding Edward well, he governed his words as there would be other times to satisfy his curiosity.

“Currency,” Edward softly mentioned with a smile while looking upon Logan’s handsome face. Logan was the very image of his father at his age. More so than his brothers who had inherited their mother’s rounded features, while those of Logan were elongated and his deep blue eyes captivating of spirit. Logan also had his father’s calm analytical nature and steadfast of opinion. Young Hamish was more doubting while Ned was caught somewhere between his brothers appearing not to understand his position.

Logan repeated the word displaying a confused brow.

“You don’t hear it mentioned as much these days but it was a way to describe the likes of you and your brothers back before you were born.”

“Why currency?” Logan questioned.

“It denotes those first born to convicts and was supposed to be discourteous, yet it became their pride and most proudly did the young wear it. It was often said those who came from England were sterling and those borne to convicts were currency.”

“I have heard it said but never knew its meaning,” Logan admitted and repeated the word, “currency, I like that, I’ll use it on Chance on our next meeting.”

“Ah lad but there lays your error,” Edward corrected with a challenging laugh.

“Why so?”

“Chance’s father Piers could be considered currency as he was born to convict parents but not Chance.”

“I’ll still use it,”

“You do that lad,”

Edward felt the warmth from their conversation and with Logan’s words was the memory of a youthful Hamish so many years previous. For a moment he was back on the Wilcox farm and remembering the day Hamish came to them. It had been during market day at Parramatta while selecting a servant from the convicts offered. A right collection of rogues they were and recently from the ships, strongly displaying the resentment of their chains and the sentence of transported for twenty years, with never to return still ringing in their ears.

Selecting a servant was like selecting a horse or a prise bull, all but checking the teeth but caution was still advised, as many on offer had belief if they headed north they would eventually reach China, so as soon as the opportunity arose they would be gone. If not they came from the dregs of society and thought nothing of robbing their master or shirking from work at every opportunity.

Many escapees were found days later done in by the natives and left to rot like carrion under the southern sun. Some more lucky found shelter with the natives and lived their days partnered to a black woman with a number of half-cast kids that knew no god and spoke no English. For most it was fear of the blacks and reports of those who were done in that kept them from bolting. Some learned how to read the bush and lived like hermits in the foothills and gullies of the mountains, dodging blacks and white alike.

Parramatta market day had been busy and many gathered around the newly arrived convicts, either to gape at their misfortune or obtain a servant for their small holdings. The best, youngest and strongest of the lot were soon taken up by the more to do settlers in the likes of John Macarthur and the remnants of the Rum Corps’ officers, leaving but the old, lame and rebellious.

What is your name? Sam had questioned his selection.

I no longer have a name, Hamish had roughly answered while refusing to turn his proud eyes from Sam’s gaze.

It was then the convict supervisor waned, if selected this one would soon cut your throat but Sam saw something in the man and despite the warning he selected Hamish. Edward remembered the look in Hamish’s eyes and could see that once there was a soul. He may have appeared to be a savage but with a little kindness from Sam Wilcox, as had been shown earlier with Edward, Hamish again found his humanity and Edward a life long friend.

Across to the east a storm was developing dark and menacing while hugging the tall mountain tops. Edward pointed towards the blue grey smudge along the horizon. “Rain,” he simply said.

“You are always correct when it comes to the weather.”

“I had a good teacher,” Edward proudly admitted.

“Would that have been your black friend Bahloo?”

“It was and a truer friend one could not find. Did I tell you Bahloo once saved my life?” A smile took away Edwards brooding for the past and long gone friends.

“No,”

“It was long ago when I was bound over as a servant with your father to Sam Wilcox on his farm near Parramatta. They were difficult days and the settlement almost failed and starved, instead of much wanted supplies from England they sent more convicts.” Edward commenced to wander from Bahloo’s brave action, “yes for many years the colony’s future was uncertain and there was talk of moving it elsewhere, some suggested South America but the coalition war of ninety-six with Spain soon put an end to that idea.”

“Wilcox; that is Chance’s family name; were they related?” Logan asked disregarding Edward’s diversion with his historic drift.

“No Piers adopted the name after his parents drowned and Sam took him in. I can still remember the first time Piers arrived at the Wilcox farm and so caked in river mud it was difficult to know if he were black or white, while almost starving and delirious and hardly remembering his name. He had survived a great flood but his family perished.”

“I remember Chance telling me something like that,” Logan released a chortle, “your past as well as that of Piers is a jumble to me, I can never get my head around it all, too many characters, too much coming and going; but what of Bahloo saving your life?”

“Bahloo,” Edward simply spoke with a smile as he appeared to drift back towards the Acacia stand and he bones of his black friend.

“How so Uncle?”

“It is a long story, possibly another time.”

“I don’t remember Bahloo,” Logan admitted.

“He was from the Burramatta tribe but had family connections locally here at Fish River, we reacquainted after your father and I settled here.”

As Edward spoke he spied Hamish coming from the woolshed, “your brother is coming up for his lunch; I guess I should be getting it ready.”

“I’ll do it,” Logan offered.

“Thank you,”

“We need a housemaid,” Logan suggested.

“Tis true, or one of you three to wed;” A smile a wink but nothing more.

“Before Hamish arrives I have a question,” Logan became most anxious.

“What would that be?”

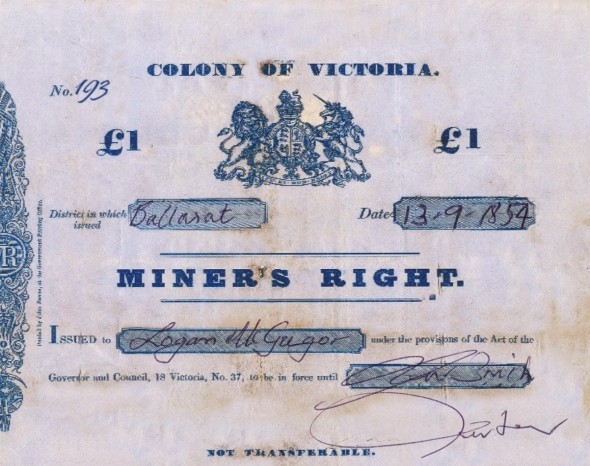

“I would like to try my luck at the Ballarat goldfields and as Hamish is my guardian he is reluctant to agree.”

“Can’t you wait a year when you will be your own man?” Edward suggested.

“The gold could be all worked out by then.”

“Why do you wish for gold Logan, have we not given you a fair share in the Estate’s profits?”

“I’m grateful for so uncle but it does not come with adventure, I need to experience the world, not sit back and watch it pass me by, besides -.”

“Besides what Logan?”

“You and dad had your adventure.”

“Not from choice I must correct. We’ll speak of it later,” Edward whispered and touched the back of the lad’s hand as Hamish approached closer.

“What are you two plotting?” Hamish called as he climbed the rear steps. At half reach he paused, his eyes searching deeply into those of his younger brother.

Logan refused to break from his brother’s stare.

“Dinner won’t be long, Logan was saying we need a housemaid or you and Edward should wed.”

Hamish commenced to laugh; “is that right young brother?”

“It was only a suggestion,” Logan softly defended.

“When you turn twenty-one you can do so yourself.”

Hamish dropped his hat onto the table beside the empty beer bottles, “isn’t it a little early for you to be drinking Logan?” Hamish’s voice lowered into displeasure.

“They were mine Hamish,” Edward admitted.

“Sorry uncle, only the lad is becoming somewhat recalcitrant of late.”

Edward laughed at the use of the word.

“What?” Hamish curiously asked.

“I was remembering your father; he had a way with words, always discovering new words and trying them out on people.”

“About this housemaid what do you think uncle?”

“I don’t mind playing maid it keeps me occupied now the running of the estate is left to you and young Ned.”

“I think Logan would look just dandy in a dress, maybe he could play housemaid,” Hamish paused and being amused by such a thought he repeated it; “just dandy.”

Logan gave his brother a disapproving glance but kept his quiet.

“What do you think Logan?” Hamish continued with his usual discouraging wit.

Hamish!” Edward gently protested as Logan departed company to prepare his brother’s lunch. Once beyond hearing Edward spoke, “you shouldn’t pick on your brother.”

Out of respect for Edward, Hamish instead diverted conversation to the need to find shearers for the approaching season and how difficult it would be as most had left for the southern goldfields.

“There’s always Piers, he was once a shearer when we first came across the mountain, and Sam, even his brother Chance could be considered.” Edward suggested.

“Piers?” Hamish quizzically questioned.

“Yes Piers why do you question so?”

“He runs a staging inn, what would he know of shearing?” Hamish blustered forth his words in jest.

“He once was part of this estate before he married and sheared here for many seasons.”

“I forgot but that was before my time, besides he’s a little out of condition for the work, to much ale and -” Hamish cut short realising he was about to disclose the man’s private affairs, or more to point rumours that quietly circulated.

“And what Hamish?” Edward asked while picking up on Hamish’s unquantified account.

“Never mind, I should think I can muster up enough to do the job, there has been a number of drifters around Bridge Town of late and being down on their luck would be thankful for the work.”

What Hamish had neglected from his description was Piers had become somewhat sedentary from the good life, while rumoured he spent more time than socially accepted visiting the local native camp and its women, even as far as siring a child to one but that was rumour and that kind of talk was common about. It only took the sighting of a newly born half-cast child at the camp to covertly place the blame and anyone with influence was fair game.

As for Sam, Piers’ eldest son, he had little interest in anything except complaining and fighting, he was a lump of a lad with attitude and a quick fist, although on the occasion he did help out on the property but usually labouring but never shearing.

Edward appeared to once again drift towards the shimmering grave stones beside the acacia stand. He mentally counted the markers before referring his sight back to the unmarked spot of his native friend Bahloo. ‘I should erect a marker for Bahloo,’ he thought, ‘but would Bahloo wish for stone, no I think not, possibly something carved from timber. The red gum that was his totem, he would like that. Ned is good with tools and joinery, possibly he could do something.’ Edward released a slight huff with the thought.

“What are you thinking Uncle Edward?” Hamish asked.

Edward withdrew from the past, “I was remembering your father and the early days.”

“And other’s I expect.”

“Yes Hamish and others but I’m afraid it won’t be long now and I will join them.”

“You are yet young,” Hamish disagreed.

“Yes young but old and have outlived them all.” A deep sigh as Edward returned to his seat. “I won’t be capable in helping with the shearing this season,” he regretted.

“You have done more than your share,” Hamish assured while glancing towards the kitchen for his midday meal.

“In my day I could out class any shearer west of the mountains and never soiled the clip with a drop of blood,” Edward proudly announced.

“You won a trophy at the Bathurst show,” Hamish recollected.

“That I did and you and your brother used it to dip tar during the shearing. As for nicking the sheep,” Edward gave a wink and a smile that gently accused.

“Only cut the rams it gets a little difficult around those large cods of theirs.”

Edward laughed with the thought.

“Yes I remember the look you gave when you discovered your trophy covered in sticky black tar. I thought we were right in for it,” Hamish admitted.

“And you accused Ned.”

“And he me but in truth it was Ned but I admit it was my suggestion as I couldn’t find the dipper.”

“I wonder what happened to the trophy.”

“I only saw it the other day; it is in the sheering shed in a corner behind where we stack the bale sacks and has a great big huntsman spider living in it. Mind you the tar is now so hard it could never be removed.”

“Never mind, I don’t think anyone would be interested in my past shearing abilities.”

Again Hamish impatiently glared towards the kitchen and his lunch, “Logan, I have work to do, I can’t wait all day.”

“It’s ready,”

“Another thing Hamish, young Logan, I think it is about time you cut him loose a little, he needs to make his own mistakes in life,” a smile, “or make his fortune or failures,” Edward suggested.

“Don’t tell me he’s still on about chasing gold,” Hamish snapped.

“He had mentioned so,”

“I promised father I would give him guidance and until he is of age that I will do.” Hamish released a breath of annoyance towards his younger brother’s insistence on travelling.”

“Then I will leave the matter to your judgement,” Edward considered.

“Appreciated Uncle but the young fellow needs to learn respect and the value of hard work and quickly.”

“All I will say is don’t push him too hard or you may lose him for good.”

“Then be it so.”

The only payment our authors receive are the emails you send them. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

28,019 views