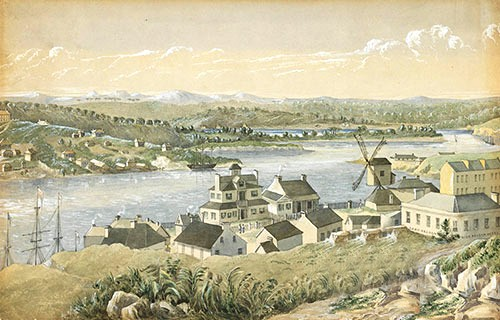

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 15 Apr 2019

There was a carnival atmosphere as the farmer brought his cart loaded with produce to the Parramatta market. Mid-summer and a warm clear day, many had taken the boat ride from Sydney to the lawn party at the Governor’s country residence, being his retreat away from the smell and trade of Sydney and its over representation of taverns, cheap bars and brothels.

On the village green a game of cricket was in progress the teams, convicts verses the soldiers from the local barracks. The convict side was given the name of Antipathies while the soldiers were the Barrackers and for once there was a general air of harmony between prisoner and keeper.

Edward had never played cricket but knew well its code, as his father and older brother played for the local village tavern, his father their champion batsman while his brother was accomplished at bowling. As they passed the green he enquired of the score, releasing a wry smile on receiving the answer. “Why it is but over and the Antipathies have still four bats in hand with only twenty runs to win.”

“Did you ever play cricket Sam?” Edward asked as they moved away from the game in progress.

“I never had the time lad, being the oldest boy it was my position to look after the younger children. By playing age my mother became ill and it was up to me to nurse her.”

“How many were there?” Edward asked.

“There were seven of us. I have four brothers and two sisters.” Sam answered as a rare shadow of remorse clouded across his eyes. “You know a strange sensation just came over me,” Sam admitted, “for an instant I was back home and it was Christmas, we didn’t have a lot but we certainly made merry and I could clearly see them all gathered about.” There were tears in Sam’s eyes but he managed to keep them private, instead he released a wide smile and changed the subject. “We’ve plenty of peaches for the market lad, should make a handy profit there.”

“I miss Christmas,” Edward sighed.

“We will have a grand on this year if only to cheer you up.”

“It’s not the same; there should be snow, turkey and dumplings with roasted chestnuts and holly, not boiling heat, flies and mutton.”

“I thought Christmas was in the spirit of the occasion, not in the trimmings.” Sam said.

“It is Sam but I miss the snow.”

“As you often say but think of all these peaches, they should remind you of home.”

Sometime before Edward arrived, the farmer had planted a number of peach trees and this year they came of age, fruiting well with so much produce Sam made peach wine, while the remainder he brought fresh with the wine for sale at Parramatta, or to be exported down river to Sydney.

Some of the fruit he offered to the local natives, who took an instant dislike to their sweetness. True, they did appreciated the local native bee honey and sugar bag- an ant that stored sugar in its abdomen also raw cane sugar but the peaches were most alien to their taste and with an unceremonious spit were quickly rejected.

Sam also had a good crop of potatoes, climbing beans and pumpkins which he quickly sold and once there was little remaining, he and Edward went to the big house to watch the sports day competition. There were foot and horse racing, greasy pig, greasy pole for the children, boxing gymkhana for the adults and the local vicar ran a lucky dip, a penny a dip with prizes being made and provided by local women. Oddly the most expensive prise in the form of a pocket knife for the luckiest dipper was never found. Even so nobody became upset with the suggested sham as the collection was for the orphanage.

By the end of the day the farmer had made a good profit with a small purse containing many coins of varying degree in value and country of origin, which he hadn’t counted lest he would be notice. The bag was hidden in a secret compartment at the base of the cart’s flooring as good a place as any to store his takings. Already he had been bailed up by bushranging convicts, who failed to find anything of value and went on their way without further confrontation, one cheeky character did take a liking to Sam’s straw hat, keeping it in lieu of not finding anything else worth their effort.

The way home was first some distance along the Parramatta to Sydney road before turning along a well travelled track on a branch creek of the river. A short distance out of town they chanced upon Gregory Blaxland riding with Macarthur, who appeared to be chasing imaginary flies away from his tortured expression, while constantly mumbling to himself. Macarthur kept riding without even the simplest greeting but Blaxland paused and spoke with the farmer.

“Mr. Wilcox, have you any of those lovely peaches left?” Blaxland asked remembering seeing the trees and ripening fruit on an earlier visit.

“Most have gone to peach wine or were sold this very day at market.”

“Pity,”

The farmer reached behind and produced a bottle of his wine and a number of peaches. Passing them to the explorer they were quickly placed in a saddlebag.

“I’m afraid they aren’t the best, they were mostly bought by the Governor’s cook.”

“They will do just fine,”

“What about Mr. Macarthur would he also like some?”

“I’m afraid Mr. Macarthur isn’t very well at the moment.”

“Oh I am sorry to hear so.”

“Not in body but in spirit, he’s legal grant has again been negated and he is mentally penning his next complaint to London.”

“So I heard in town.”

Macarthur turned and made gesture he wished to be gone, as he did so Sam called his greeting but received nothing but the man’s back as he slowly guided his mount along the side of the road.

“Another word Mr. Wilcox, the governor is planning to travel to the newly discovered land at Bathurst Plains sometime in the future,” Blaxland turned to Edward, “would your boy like to travel with him.”

“Edward is his own man now.”

“Oh my apologies so he is – Ed would you be interested in accompanying the Governor on his trip?”

“It will depend on Mr. Wilcox and the farm,” Edward politely answered.

“Certainly but it wouldn’t be until mid-autumn and during the down period. For now I’ll leave the thought with you.” Blaxland lifted his hat nodded and quickly rode off to rejoin with Macarthur who had impatiently discontinued his journey while waiting some distance ahead.

“What do you think Edward?”

“Don’t rightly know, let’s see what autumn brings.”

Nothing more was related on the subject but as the creek and the turning towards the farm came into sight the farmer cast his gaze to the western sky, the mountains and the dipping sun. Taking a deep breath he spoke, “we need rain.” Edward nodded his agreement.

“The creeks down, Ted Rowland can’t get his skiff further than the second bend now.”

“That I’ve noticed.” Edward concurred.

“And there was a shepherd’s warning this morning.”

“Red sky at night shepherds delight, red in the morning Shepherds warning,” Edward uttered the ditty as he looked to the west and the setting sun, “it’s also red tonight,” he ironically offered.

“So it is,”

“You can’t have a delight and a warning at the same instant.”

“In this country Edward, you could get anything.”

“I’m beginning to understand that.”

“Dust,” the farmer simply said from some distant thought.

“Dust, what do you mean?”

“The red sky, it’s only dust, not god, not the devil just dust and there is always flaming dust.”

“Red sky or not, we still have enough daylight to bring water to the new crop of greens.”

As Edward spoke, a large grey kangaroo bounded across their path some distance ahead, followed by a second then a third. The cart horse tossed and snorted but soon settled as kangaroos were becoming a common sight now many of the water holes away from the river had dried.

“They seem to be in a hurry,” the farmer induced and with his words came the reason, a number of large hunting dogs bounded at full pelt after the kangaroos, closing in at every leap. Shouting followed from the undergrowth and soon three men approached in a puff as the dogs brought down the slowest ‘roo. The men paused to catch their breath at the cart. The hunters were from the timber camp a short distance up the branch creek and out for their sport.

“Mr. Wilcox,” the first of the men greeted, his breath commencing to normalise.

“Mr. Herring,” the farmer simply answered as the dogs gave up on the downed ‘roo and commenced after the rest.

“Nice set of hunting dogs,” Sam acknowledged.

“They belong to Henry Perkins at the logging camp. I’m exercising them for him.” Puffing heavily he called to one of his associates, “Joe you get after the dogs, I’m rooted,” he ordered as he leant against the cart, spitting a large globular of phlegm onto the ground, his chest wheezing through lack of condition and cheap tobacco.

“Good hunting,” the farmer sarcastically enquired.

“Good enough exercise for the dogs,” Herring admitted still finding his breath hard to come by.

“You do realise there isn’t enough game at this time of the year for the blacks?”

“Bugger the savages they can move back across the mountains, I’m sure they will find enough over there.”

The farmer wished to take the argument further but decided he was already thought of as a bleeding heart towards the indigenous people and words would only fall dumb on such an audience.

At last Herring found his breath and gave a loud whistle, bringing two dogs back from the chase, others took much longer. With the dogs came the men, laughing as they travelled being most impressed with the dogs work. On reaching the track all men with their dogs departed along the creek back in the direction of the timber camp.

It was soon discovered one of the downed kangaroos was still alive and in great trouble, “come on,” the farmer said and jumped down from the cart and with Edward close, came upon the mortally injured animal. Collecting a sizeable stick the farmer lifted it high above his head and brought it down with full force upon the kangaroo’s head, a kick a second and it was still. Edward called from a second ‘roo, “this one is dead Sam, as is the third.”

“Collect the ‘roos and we will take them up to the native camp, there’s no sense in wasting fresh meat.”

It was almost dark as they came upon the native camp, finding a general degree of lethargy, women preparing the evening meal, children somnolent from a day of activity and men gathered in quiet conversation. The approach of the two was well noted long before the cart arrived and as they came into the clearing, the children hid behind mothers as they backed away from the intrusion.

The farmer called upon the closest native, who not understanding his meaning spoke curiously to an old grey bearded native sitting cross-legged before a bark humpy, while whittling at a long piece of wood with a small iron axe, either bartered or stolen from some local farm.

“Are we missing a hatchet?” Edward quietly asked Sam.

“Be nice you don’t want to wear the thing.”

The old man called and Bahloo came to the front.

“Edwa,” the lad inquisitively spoke.

“Bahloo, we have some fresh meat for you.”

The native lad approached the grey bearded old man, who if anything appeared puzzled as Edward jumped from the cart and soon had the three dead kangaroos on the ground for inspection. The men slowly came to the carcases. One bent towards the dead kangaroos, “dwerda,” he said then his associates repeated the word and fell silent.

“Bahloo what is dwerda?” Edward enquired.

“Dogs – but not our dogs they Gubba dwerda.”

“Yes they belonged to the men at the timber camp,” Edward admitted and on doing so Bahloo addressed the others in language. They immediately became animated and shouted among themselves, becoming quiet at the insistence of the old grey bearded man who spoke softly to Bahloo. The lad turned to Edward, “Deman not happy with Gubba dwerda, they kill for play and not for tucker, he say he happy with food but you go now.”

“Will you call on me tomorrow?” Edward asked. The lad nodded his intention as the others once again broke into heated conversation.

“Why are they so unhappy?” Edward asked of Bahloo.

“Gubba men with dogs they came here and took two girls back to their camp.”

“Why?” Edward innocently enquired.

“Isn’t that obvious, come on best we go from here.” Sam turned the cart and headed out.

Early evening there was much commotion from the direction of the native camp, even more so than occurred during initiation ceremonies. Occasionally Edward would stand at the hut door and inquisitively gaze towards the direction of the camp, feeling somewhat unnerved by the outcome of their earlier visit. “What do you think?” he eventually asked of the farmer.

“I think it’s all getting somewhat heated and if we aren’t careful we’ll have a war to contend with.”

“That bad,”

“I’m afraid so and not for the first time and with the likes of those from the timber camp, no one will be secure.”

“Should we warn the timber camp?”

“I would think not, it would only encourage them to attack the natives, besides it may come to nothing. A night of singing and dancing and complaining, the spearing of a couple of bullocks and with the new day it all may settle.”

“All over the killing of a couple of ‘roos,” Edward answered somewhat flippantly.

“Not the taking of their game but it all, the land, abducting the women, hunting grounds, sacred sites the lot, it has been building for months,” the farmer released a long sigh of concern and went about preparing their night’s meal.

“Why can’t we all be more like you Sam and there would be no trouble.”

“Wouldn’t matter if all were,”

“Why not,”

“If all were sympathetic and with more arriving on each boat, eventually there would be so many sympathises there wouldn’t be room left for the blacks, then sympathy would turn to something nasty.”

“Do you believe the settlement will continue past its use as a prison?”

“It already had lad, what do you think we are doing and the likes of Macarthur, there are boat loads of his friends and financiers arriving by the month, soon even the land beyond the mountains will be brimming with free settlements.

“Like my promised thousand acres?”

“Yes like that but it’s the same the world over and always has been and always will be. The problem now the world is mostly discovered and there aren’t too many native lands left for Europeans to conqueror.

After dinner Edward sat on the porch to enjoy the cooling air from the ocean. All about was quiet then the singing at the camp commenced once again, except louder than before. The farmer came to the door.

“Nice breeze,”

“Tis,”

“Nice singing,”

“You think so?”

“That was derision, it sounds like a mob of chickens squabbling over some grub,” the farmer gently mocked.

“Yet it does have a certain rhythm,” Edward evoked.

It was well into the early morning before the singing died away and the breeze swung about and came warm from the west. Edward came back into the hut and his bed, “you awake Sam?”

“I am,”

“Singing has stopped,”

“So I’ve noticed,”

“Bahloo is coming over in the morning for more English learning; I’ll ask him what’s going on.”

“How are you going learning their speak?” Sam asked.

“Not as good as he is with English.”

“He seems a good kid but he still wants to bed you.”

“Wanting is one thing, doing is another.”

“Wouldn’t you like to do so?”

“As I’ve already mentioned, it wouldn’t be right, besides he smells something rank; I don’t think I’d like to get that close to him.”

“That is what they say about us?”

“What’s that?”

“We smell bad – goodnight.”

Edward was carrying water to the vegetable patch when he notice many of the native men, well armed and on their way across the branch creek but there wasn’t any sign of their woman digging for yams and no Bahloo. He waited past high sun before retiring for lunch while becoming somewhat anxious for his newly found friend.

“You appear concerned,” the farmer suggested as Edward sat silently through his meal.

“Not so much concerned but curious, usually if Bahloo says he will come he arrives and with much enthusiasm.”

“Don’t forget he is a member of an extended family and Deman is his grandfather and you saw for yourself he and the others were somewhat dismissive with the action of the hunting dogs.”

“You as I, have taken the odd wallaby or ‘roo, nothing was said then,” Edward said.

“True but this isn’t the first time the timber men set their dogs on the wildlife, even once on the natives themselves before you arrived. I had necessity to stitch a couple of nasty bits myself and there is the taking of the two girls.”

“I should go up to the camp and see what’s going on,” Edward suggested.

“If you want my advice, don’t. Bahloo will come to you when he is good and ready.”

Edward accepted the farmer’s advice and kept to the fields, while occasionally casting his gaze towards the tall trees leading to the native camp. Late in the afternoon the native men returned and crossed deep within the top paddock but not once did they turn their eyes in the direction of the hut.

The second day was similar, with the natives keeping well to the edge of the farm and crossing over the branch creek, this time later in the afternoon but did not return with the setting of the sun, while on the following day none were seen at all.

The following morning came a visit from one of the loggers on his way to Parramatta. On seeing Sam and Edward working in their fields he approached.

“Henry Perkins,” he introduced, “Mr. Wilcox I believe,” he added somewhat sombrely.

“Tis so Mr. Perkins,”

“The black are at it again.”

The farmer leant on his hoe but remained silent. Edward kept to his work.

“Last night they speared my flaming hunting dogs, four of them stone flaming dead, along with my breeding bitch.”

The farmer grimaced but kept his calm, what he would have wished to say being it was the man’s own fault but doing so would only make one more against his leniency towards the natives.

“I’ll be getting the Chief Constable to do something about it, so expect a visit, in the meantime I would advise you to keep an eye, or it may be more than dogs next time, the flaming savages are a little too handy with them spears of theirs for my liking.”

“I’ll take your advice Mr. Perkins,” Sam cordially answered.

“You do that, I hear tell you mollycoddle them.”

“Not so much so, mostly only allow passage and smile somewhat.”

“You may regret so Mr. Wilcox.” Perkins turned his horses head and once again headed out.

On the following day while collecting bucket water for the vegetable patch Edward notice a skiff holding near on a dozen well armed men tacking upriver with the afternoon’s south-easterly but they were too distant to be recognised. His first thought was how they had managed the shallows and the sandbar downstream. Believing it was a light craft and with so many passengers it could be carried the short distance. As for their intention, he considered they might be relief workers for the timber getting but why would relief workers come with so much fire power.

Edward waved to the men and they returned the gesture without conversing across the distance. Leaving his buckets on the bank he returned to the hut and shared his sighting with Sam.

“Possibly it’s a revenge party for the killing of Perkins’ dogs.”

“What do you think they will do?” Edward asked.

“Couldn’t say but if their blood is up it could be a massacre, yet seeing there are only a hand full of constables and the native camp holds at least thirty capable men even more, I guess it will be a good talking and little else. It’s the timber workers one has to watch, if they think justice hasn’t been accomplished they may take the matter further.”

It was the safety of Bahloo that remained most concerning for Edward and that of the women who dug for murnong near the potato patch. Sometimes when heads were turned they would dig some spuds and laugh issuing much banter and now he was learning language he found them quite humorous. As for Bahloo’s slant on sexuality, it was never imposed and with passing time when with Edward it appeared to be absent from his nature.

“Will you take a woman?” Edward once asked of the lad.

“No woman,” a definite rejection.

“Then a man?”

“No Bahloo will be only Bahloo always.”

To Edward those words had been poignant, yet possibly they described his own situation, perhaps there would ever only be Edward Buckley and a memory of what was or could have been in a different world. He wished to tell his black friend of his love for James but could not. James was sacred to his thoughts and could not be shared in passing conversation like some trinket one holds to the shelf, only to bring it down for show or dusting when the mood dictated.

The skiff appeared to glide into the grassy bank beside the native camp, sending bare black arses of children to scatter and a number of spear carrying natives to gather at safe distance from the landing. Chief Constable O’Brien led his men ashore and called upon the natives. Grey bearded Deman stepped forward and waved a hand at the troop, “wara, wara, wara,” he shouted and defiantly turned his back towards his adversary.

“Hey you come here!” the constable shouted, demanding so with a gesture of hand. None moved while his men lifted their rifles.

“Ready to fire boss,” one eagerly declared, his finger trembling on the trigger.

“No lower your muskets if you value your balls, there are too many.” The muskets lowered but remained cocked and nervous. Again the constable waved his demand bringing Deman a step closer but remaining noncompliant. Others gathered close by the old man while loudly chattering in language and making repelling gestures.

“Mr. Perkins,” the constable called, bringing the timberman with musket ready to his side.

“Which one of these black savages killed your dogs?”

“Can’t rightly say, it was dark and the buggers all look alike.”

“Then you choose a couple and we’ll take them back for the army to deal with.”

“I guess the closest and less aggressive will suffice but I still reckon we should scatter them with a quick volley of shot,” the timberman anxiously suggested.

“Settle down Mr. Perkins that can be done at a later time when there are less of them and we aren’t so open to attack,” the chief constable quietly admitted.

As the constables held their ground a strange occurrence became evident, the natives disregarded the Gubba and went about their morning business as the women gathered the children and silently slipped into the scrub.

“I don’t like the look of this,” Perkins admitted.

“Settle Mr. Perkins, there’s nothing out of the usual yet, I’ll tell you when to worry.”

While going about their business two of the natives chanced to pass close by the constables giving O’Brien the confidence he wished for, “grab the black bastards!” he shouted and a number of his group quickly took the two under control and dragged them shouting all hell towards the skiff. Then the expected standoff begun, constables with muskets cocked lined the bank, natives with spears closing in but apparently reluctant to release their darts.

“Hold it! Hold it!” O’Brien shouted as the two natives were quickly bound and unceremoniously dumped into the skiff, “slowly retreat, no one fire and I mean that, any man who discharges his weapon will be put on a charge of insubordination, if any remain alive for me to do so.”

Cautiously one by one and in silence the constables returned to the boat, while the natives stood with spear arms tight and armed awaiting Deman’s command but such was not forthcoming as he knew well what would be the consequence if he were to speak.

As the skiff pulled away into midstream there came a volley of rocks, mostly from the women and younger lads, one hitting a constable with much force possibly breaking his arm, if not, giving enough pain for him to discharge his musket but missing all, the ball hissing through the branches of the nearby trees dropping a small amount of leaves. The firing did scatter the natives but only to a safe distance where they again gathered more projectiles.

Soon the skiff was far enough down the branch creek to be out of throwing range but a number of the braver natives did follow along the bank, now hurling abuse instead of stones. At a bend in the branch the scrub grew thick close to the water and it became too difficult for the natives to follow further and a safe distance was at last realised.

“That was easier than I inspired,” Perkins sighed in relief, “but to my mind we should have brought a few of the buggers down.”

“You get to know their ways, we didn’t catch these two, they were offered. It was their opinion better to sacrifice two than two dozen, even if they managed to spear most if not all of us. They will consider revenge on another day.”

“Is it your thought we could be attacked at the logging camp?” Perkins asked.

“More than likely, yet they are like children and may soon forget but I would mind your guard for a while.”

“That is easy for you to say, we have to go out into the bush for timber and can’t hold a musket and axe at the same time.”

“Cause and effect Mr. Perkins.”

“What does that mean?”

“You killed their tucker in sport and I believe stole their women, they killed your dogs, and we took prisoners – cause and effect.”

“That’s alright for you safe in Parramatta,” Perkins complained.

“We can’t be everywhere and it is you who wishes to live beyond the pale. I’ll speak with the army, possibly they will supply you protection for a while. There is one possibility.”

“What would that be?” Perkins became curious.

“The Hawkesbury incident;”

“Explain,”

“It wouldn’t be for me to say but as I recollect flour laced with rat poison was laid for vermin.”

“Are you suggesting I should use poisoned food Mr. O’Brien?”

“I’m not suggesting anything Mr. Perkins, only relating a tragedy that occurred on the Hawkesbury.”

It had been some time since the capture of the two natives from the camp and after returning to Parramatta they had been chained to a tree adjacent to the police station as an exhibit, while deciding what was to be their future. Perkins was still smarting from the loss of his hunting dogs and wanting further revenge, with the military more concerned in not starting a race war, so for the time there was an uneasy peace between the natives and timbermen.

It was a well known fact the natives were numerous around the Parramatta district but usually too fragmented to gather in large numbers, yet once they believed strongly enough in some issue they would gather and reap revenge by the spearing of a lone rider, or burning of corn fields and huts. Sometimes with the help of escaped convicts the natives became most adapt in guerrilla warfare but fortunately never learned to handle firearms, although a number of weapons had been stolen from remote farms.

At the farm, life went about its daily labour. Edward would often cast a caring glance towards the tall trees in the direction of the native camp, expecting to see the happy face of Bahloo coming from the scrub, his hands hight and waving, his voice in full tune with a loud cooee, much whooping and a variety of bird calls.

He will come when ready, was Sam’s guidance when Edward again suggested he should visit the camp delivering a supply of produce. Edward once more took Sam’s advice but still searched the scrub for signs of his friend while he worked the field.

“Those spuds are ready for lifting.” Sam suggested as he passed by the patch, he also noticed the lack of disturbance at the native yam patch. “So are the yams,” he affixed.

“I’ll get on to the potatoes this afternoon,” Edward agreed while unconsciously scanning the scrub.

“I’ll give you a hand – lunch time.”

“Righto, I’ll finish this section and be along soon.”

Sam was almost back to the hut when Edward’s attention was drawn towards the scrub and to his relief a number of the woman returned, with them was Bahloo. Edward called and waved without receiving acknowledgement. He called again. The women quickly walked to the yam patch and commenced digging. Eventually Bahloo broke away from his work and approached Edward, pausing some distance away.

“Are you alright Bahloo?” Edward quietly asked.

“Bahloo alright,”

“I heard what happened at your camp.”

“I’m not allowed to visit,” the lad admitted without referring to the abduction.

“Yet you are here.”

“Bahloo likes Gubba.”

“So it’s Gubba now. What has happened to Edwa?”

“Edwa still there but Deman say you Gubba.”

It was obvious the lad had been instructed in what he should converse, even so there appeared to be defiance in the lad’s tone and by the women’s expression, displeasure with his approach towards Edward.

“Is Deman angry with Edwa?”

“Deman angry with all Gubba.” Bahloo lowered his eyes away from Edward then turned his gaze back towards the women. They appeared busy with their digging allowing him to continue.

“Are Sam and I safe Bahloo?”

“Sam safe,”

“Is Edwa also safe?”

“Edwa safe.”

“You know we wouldn’t do anything to harm you or your lot.” Edward insisted.

“Deman say that but we must still call you Gubba.” As Bahloo spoke it was noticed the women appeared to be satisfied with their collection and called for Bahloo to return.

“Bahloo must go,” The lad spoke but remained stead to the ploughed earth beneath his feet.

“You will come again?” Edward asked as the women paused at the fence line, again they called for Bahloo to come away.

“When Deman says so,” Bahloo turned on his heals and quickly joined the women as they melted into the distant trees. Edward rejoined with Sam.

“How did that go?”

“Somewhat dispassionate I’m afraid and he said Deman has forbidden him to speak with us.”

“Yet he did,”

“He also said we were not in any danger.”

“That is pleasing but if it overheats the old man may not be capable of controlling the younger men. Come on lunch is ready.”

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,230 views