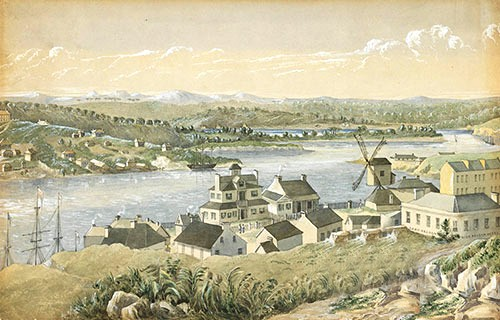

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 8 Apr 2019

Summer arrived with blistering heat but no rain and the crops had totally failed in the Parramatta district, while that on the Liverpool Plains and along the Hawkesbury struggled but survived and around Newcastle to the north there was light flooding. So be the anomalies with weather in this far southern land, one farm could be in drought while the neighbour well watered and then with the corn ears plump and golden, almost ready for plucking, comes storms with hale stones as big as one’s fist while flattening everything, or if the storms fail to take you out, plagues of locusts arrive in a green black swarm, leaving nothing behind but stalks of brown and bare parched earth.

The crossing of the Blue Mountains had given many fresh hope, while even without Government permission folk were heading west at an alarming rate but keeping close to the crossover not to become too isolated from the settled arrears. There was even reports gold had been discovered but such rumours were soon quashed. New South Wales remained in large a penal colony, with convicts still far outnumbering free settlers almost three to one and there was fear a gold rush may spark rebellion, or have those of usually sound reasoning drop tools in the frenzy and leave the colony without a work or defence force.

What gave further concern to Macquarie, there wasn’t any law beyond the mountains and each free selector became their own law, their own protection and provider. Within a very short time bushranging became the favoured pastime for escaped convicts as well as free men down on their luck, so it was deemed beyond the pale to be discovered there but like most viceregal decrees was mostly ignored.

Such moss-troopers would camp in ambush beside Blaxland’s rough track to relieve settlers of their wealth, food and sometimes lives. Often it was the bushranger who met with misfortune and their listless carcass would be either crudely buried or unceremoniously dumped beside the track as a warning to others. In some instances left swinging from some high tree branch while crows feverously fed from their decaying flesh.

With all such trials, natives should be added to the equation. As one would expect they were not willing to allow a flood of invaders to settle on their best hunting land but slowly guns out rated spears, clubs and boomerangs, with introduced disease also dwindling their numbers, so they soon succumb or were driven further west. As for native crossings of the mountain barrier, they knew every short cut, every ravine, stream and ridge and could come and go as they pleased while easily ambush any lone traveller or small unarmed group in surprise attacks, before melting back into the thick forest. Thus it became necessity to travel in number and always with at least one firearm as the natives had soon found respect for the gun’s ability.

During that summer there was much talk of a large track of good land some distance across the mountains to the northwest, an area that was named the Bathurst Plains. It had been suggested the governor wished to visit the new territory while building towards an expedition but that was arranged for the following year and too far advanced to warrant more than passing interest.

The news of Macquarie’s intention came via an old copy of the Sydney Gazette as wrapping around some fruit the farmer had purchased in Parramatta. Smoothing the pages of print across their breakfast table with the flat of his hand, he read aloud the article on Macquarie’s intention and once done asked Edward for opinion. “So Edward my boy what do you think of the governor’s expedition? Would you like to join him?”

“I don’t believe so,”

“Such work may pay well;” the farmer suggested and passed the newsprint to the lad.

Edward accepted the print, “I have heard government work pays little and often naught but keep.”

“Read that last column,” it was that item Sam found more of interest than the Governor’s intentions.

With his increasing skills the lad slowly read the article referring to a ticket of leave convict setting up a blacksmith shop in the new settlement of Richmond, on reading further he discovered the blacksmith to be his old adversary, Thomas Ingles.

“The bugger’s getting closer, Richmond would be less than ten miles as the crow flies,” the farmer suggested.

“True,” Edward answered with a wrinkling of brow and a deep dismissive sigh.

“I wouldn’t concern, it has been time now, most likely he will have forgotten you, or be too busy to bother,”

“One can hope Sam but as I said before, I think I can handle the situation now I am my own man,” Edward spoke with a measure of confidence but in truth would rather have the blacksmith further away than Richmond.

Edward unconsciously folded the page of print in half, then quarters and once again opened it to full and returned it to Sam, “what was it like for you on your passage out?” he asked.

“On the Prince Regent?” Sam answered and folded his arms across his chest.

“Was that your ship’s name?”

“As far as the cape it was but it came to grief and we were transferred to some Dutch merchant ship – The Rotterdam, if I recollect correctly.”

“Did the Prince Regent sink?”

“Not sink but was leaking badly; it was an old naval tub and couldn’t take the southern swells.”

“You were therefore lucky to have advanced no further on the Prince Regent.”

“The Rotterdam wasn’t much better, it was a good fifty years old, full of worms and sunk on its return from New South Wales back to Batavia, it came to grief while travelling the north coast of New South Wales – why do you ask?”

“I was thinking of the blacksmith.” Edward appeared distant.

“No lad nothing like that but it did occur,” a light chuckle and continuation, “the Dutch captain was most religious and took a dim view to sexual activity especially between men and his crew was instructed to report suspicion. Anyone caught doing so; even self pollution was discouraged and if discovered there was the gloves or truss to prevent fiddling.”

“Fiddling?”

“Yes Edward fiddling, choking the chicken, lapping the lizard, you should know you do enough of it.” The farmer laughed as realisation drew across the lad’s face, replaced with the expression of a kid caught with his hand in the biscuit barrel.

“Oh,”

“It still went on. Men locked together for such a long time without women have to vent their frustrations somehow.”

“Sorry Sam I shouldn’t be so personal. I was thinking of the blacksmith,” Edward took a deep breath and stood from the table, “the work won’t do itself, I’ll be feeding the pigs.”

“That was a most unfortunate situation, I feel for you.” Sam refolded the newsprint and placed it in the wood box for the next morning’s kindling.

“Oh well, I guess Richmond is far enough away and as you suggested he has most probably forgotten me by now,” Edward concluded and departed for his morning’s work.

Mid morning there was a commotion in the top field and as the farmer poked his head beyond the hut door he called to Edward, “your mate is back with his women friends; they are singing and dancing about up paddock like one’s possessed.”

Edward came to the door as the women carrying sharpened sticks commenced to dig about in the ground at the edge of the corn field.

“It is always in the same spot, what are they up to?”

“Yams of some description I should think.”

“I’ve never seen anything growing there.”

“I keep that piece of ground free of crop for their purpose.”

“What are yams?”

“They are tubers like potatoes and ready at this time of the year, I’ve tried them but I guess you have to be native to appreciate the flavour.”

Edward left the hut and stood, hands on hips, watching the digging and singing. Bahloo paused from his work and waved, “Edwa,” he loudly called while the woman roused him for being lazy. Edward advanced towards the digging.

“What you got there?”

“Murnong,”

“Murnong, what is that?” Edward asked.

“Them our spuds but better eh,” the black lad offered one to Edward.

“Don’t think so but your English is improving.”

“Bahloo speak good eh Edwa?”

“Yes Bahloo you speak good;” As Edward spoke one of the native women stood and yabbered on to Bahloo in language before recommencing her digging, still complaining as she worked.

“What did she say?” Edward asked.

“Say me to keep digging or no dinner.”

“Would you like some of our spuds Bahloo?”

“Na no good, better Murnong.”

“Hey Bahloo where are all your young men? I only see the old folk around of late.”

“Up mountains looking for their women.”

“Wives?” Edward asked but the lad hadn’t understanding of the word. Edward once again asked with a different approach.

“They go for their women yes,” Bahloo repeated showing a measure of annoyance that his reasoning had not been understood.

“Why doesn’t Bahloo also go for a woman?”

The lad laughed and again spoke in language to the women, who lifted from their work and joined in the comedy.

“Bahloo is like Edwa and don’t like women. Bahloo is woman.”

“Bahloo Edwa no Sistergirl,” Edward protested.

The lad cast his gaze beyond Edward and gave a gentle nod towards the farmer as he stood close by the hut watching the procedure.

“Na you’ve got it all wrong, Edwa no Sistergirl, Mr. Wilcox no Sistergirl – Mr. Wilcox is my boss.”

“Mr. Wilcox Sisterboss?”

“No I work for Sam.” Still the black lad appeared confused, two men living so close had to be as he but out of courtesy Bahloo accepted Edward’s explanation. “Sam boss like your women here with you, they are your boss.”

The lad once again shook his head as his brow crinkled and the smile dissolved from his face.

“Women-boss?” the black lad suggested.

“No maybe not, let me put it another way, “Mr. Wilcox like soldiers he tells me what to do.”

“Mr. Wilcox soldier?”

“Something like that, it doesn’t matter.”

Even with his explanation Edward felt somewhat fraudulent. His general persona was strongly male; he thought male thoughts, liked male deeds and felt he could place his masculinity against any heterosexual man. The difference being he was sexually attracted to men and not women and remained deeply in love with James. A love that appeared to grow deeper as the months progressed, while pining for James’ company and closeness of his body. The smell of James remained deep in his nostrils, a musky sweet smell that he experienced nowhere else, on no other person and with the thought he almost choked with tears.

The women brought Edward back to present as they collected their yams and digging sticks, calling on Bahloo to follow they moved out. On reaching the tree line Bahloo turned and waved high. Edward returned the wave.

“What was that all about?” the farmer asked as Edward returned to the hut.

“Bahloo thinks we are Sistergirls.”

“I guess in their thinking two men living in such close proximity and without women must be so.”

“I set him straight,” Edward assured.

“What did you say?”

“I told him you were my boss.”

“Did that work with his limited English?”

“Nope, he now thinks you are my Sisterboss.”

The farmer laughed loudly, “come on in it’s almost lunch time and we have ploughing to do this afternoon after the heat goes from the day and don’t forget out little trip into Sydney tomorrow. Sisterboss what will they come up with next.”

Late afternoon and the breeze had turned bringing relief from the usual humidity. Although still some distance from Sydney Town they encountered many new dwellings and the dusty road had become a virtual highway, with traffic from country to town becoming continuous throughout daylight hours.

Often natives would gather in groups by the roadside and wonder at the passing traffic and the cart loads of strange equipment the invaders brought with them, while it was objects such as axes that most held their interested. A metal axe could fell the tallest tree in minutes while the stone-age implement used by the blacks would take most of the day, if at all and when it was necessary to bring down the biggest tree, fire would be used.

Travellers would merrily wave, using the native’s cooee call and the natives would call back and laugh and shout untranslated obscenities while offering strange hand gestures. Begging for grog and tobacco was common and if a lone traveller appeared to be vulnerable he may find himself robbed, often being stripped and left to travel naked but a lone traveller with a musket would be reasonably safe, two guns would be more advisable as the blacks were beginning to understand that once a musket fired it took some time to reload.

“What do you think?” the farmer asked as they passed a gang of convicts working to make the Parramatta road more stable during the wet. The convict road gang taking any opportunity to slacken from their toil, lent lazily upon picks and shovels as the cart passed by, while beside the road a group of four natives with hunting spears paused while pointing at the chains around the road gang’s ankles. The blacks never understood why so many able men were restricted, believing if they were warriors from some other tribe they should be killed not enslaved.

The farmer nodded and gave greeting but only received vacant expression from the gangers.

“Think about what?” Edward eventually answered as they passed through the worked area.

“Sydney and how it is growing, even since our last visit. One day this town will be a city and one proud of the Empire”

“Don’t care much for Empire Sam.”

“You still hold to your past prejudice, best to forget the past and look to the future.”

“I am still bound over for another five years or so,” the lad grumbled.

“True but we travel where we wish and enjoy most of the freedoms of a new arrival.”

“Except that of returning to England.”

“Forget England that time in our lives is done,”

“That I cannot, it isn’t the country but those who live there, family and -”

Edward paused, his thoughts were once more with James and how his friend faired. Had James received his correspondence, had he returned to his family, or what represented a family as his father and brother were naught but bullies, or was he working for some pittance that hardly sustained life itself. He released a long sigh.

“It is James isn’t it?” the farmer asked as they neared a selection of land set aside for race meetings and entertainment that had been named Hyde Park.

“That is so Sam.”

“Cheer up, I am sure some day you will once again meet with your James.”

Edward shrugged away from the conversation as a light gust of wind blew a printed page of the Sydney Gazette under the hooves of their cart horse, it shied and side stepped.

“Jump down and retrieve it and let’s see what’s going on around town.”

Edward straightened the page, “go on then read me some,” the farmer suggested as an excuse to take the lad’s mind from his remorse. Edward laughed and commenced to read, “Gunpowder tea sixteen shillings per pound.”

“It will be the cheep China tea for us;”

“Cheese three and six pence per do,”

“What’s a do?” Sam asked.

“Dunno’ possibly a misprint.”

“Than a do will do eh. What else?”

“Lamp oil two shillings a bottle.”

“That’s expensive, who is offering?” Sam asked.

“Tis Frasier’s Emporium down on the quay side,”

“So it won’t be Frasier’s Emporium for our shopping.”

“Emporium, that is a fancy name for a warehouse; hey it reads here there’s an American schooner in port, the Charles and the Governor is in a quandary.”

“Why,”

“It says England is at war with America and France but seeing that was a year previously he is undecided if the Charles should be impounded or not.”

“America is a republic.”

“What’s that?”

“No King George.”

“Is that a good thing?” the lad asked.

“Dunno’ I guess there will always be someone who wishes to be the top dog, besides for what I’ve heard the American President is but an elected king and what I understand of their motto, being all men are created equal, doesn’t extend to black slaves or their native Indians, at least we British don’t enslave the local natives.”

“That is because you couldn’t get a full day’s work out of one of them, no matter how hard you pushed.” Edward laughed.

“Too true then again I guess they have never had to work in thousand’s of years so you can’t blame them.” Sam protested.

“There is also a French expedition ship in port The Amities,” Edward moved away from Sam’s history lesson.

“I suppose being on expedition it has been given free passage.”

“I don’t like the French, my da fought against them in Ninety-three.”

“As you once said, yet he survived didn’t he?” Sam reasoned.

“I was born the year after he returned.”

“I’ve never knowingly met a Frenchman,” the farmer admitted.

“Nor I but I don’t like them,” the lad repeated.

“How can you say you don’t like someone you’ve never met?”

“Cos da said they were real mean.”

“War brings out the worse in both sides and I should think our boys were as mean to the French.”

“What makes you so forgiving of everything Sam?” Edward asked.

Sam thought for a moment and laughed; “do you think I’m soft?”

“Not as much soft but you have been through as much as I and you shrug it away as if it were but an itch.”

“There’s nothing gained by holding a grudge towards the past, it has gone and can’t be mended.”

“Possibly so but -”

“No Edward what is left after revenge?”

“Satisfaction,” Edward forcefully inclined.

“And what have you after satisfaction.”

“I don’t know what you mean?”

“You take revenge, you think you have satisfaction but the wrong done to you is still there. It is best to move on or the only person you are hurting is yourself.” Sam slowed the cart as they approached a second road gang.

“Afternoon gentlemen,” Sam greeted, giving a slight nod of the head, “hot work.”

The closest navy spat on the ground as his overseer took to his back with his birch stick. The man grumbled and continued his digging as Sam passed through the section.

“It’s a travesty,” Sam spoke in a rare growl once on their way.

“Travesty, I don’t understand the word.”

“A parody, the free settlers won’t accept us emancipated folk, nor will the convicts, we are boot scrapings to both.”

“Ah so you do know how to get your dander up.” Edward smirked believing at last found a chink in the farmer’s perfect armour.

“It’s settled down now and it was more an observation than dander.”

“I do agree, I’ve noticed the difference myself,” Edward concurred.

“I suppose I see both their reasoning.” Sam sighed and hurried their pony forward.

“Sam do you think transportation will ever stop?”

“Good question, when there is no one left in England to transport, or the free folk here demand its ending.”

“The first will never happen,” Edward answered.

“Yes but the second will and then the gentle folk of breeding back in the old country will need to rethink their opinion and value of the common man.”

“Boot scrapings – I like that,” Edward humorously admitted remembering Sam’s previous comment.

“You may use it I won’t make you pay a fee.”

“I imagine a large cowpat and splat all across the boot and I’ve had that enough times,” Edward admitted.

“Dog shit is worse, it won’t wash off and you need a sharp stick to dislodge it and it stinks for days,” Sam continued on the subject of excreta.

“There is nothing as mean as cat shit and we had a whole tribe of them on the farm, pissing and shitting everywhere, even in the house.”

“Enough of excreta we are almost there,” Sam concluded as the outskirts of Sydney proper became apparent.

At the docks the two ships, American and French were berthed quite close and both ships had armed colonial soldiers nervously guarding their gangway while there appeared to be an unusual representation of the 73rd. Regiment roaming the streets and well applied.

The American schooner, Charles, had been away from Boston, its home port, for quite some time while sealing in Bass Strait and selling the oil and skins on the China run, therefore had not heard of the war between their country and Britain. The French ship under the captaincy of Jacques Hamelin had special disposition to explore New Holland as Hamelin was a personal friend of Sir Joseph Banks and agreement, even with war raging, came directly from King George, being a man of science and farming during a rational period of his disposition.

The French captain had quickly presented to Macquarie with his papers, while the American captain, William Billing took chance and begged the governor’s grace, which was given but only as long as his stay was to gain fresh supplies.

One other consideration was taken; the Charles had more fire power that Sydney, as most of the town’s defence was aging cannon taken from old ships that were to be decommissioned and positioned away from the waterfront. By the time the cannon could be re-employed the Charles could have already played merry havoc with the town.

Once the farmer had purchased his supplies it was off to quench a thirst, so the two lead towards Hunter Street and Rosie Craddock’s, whose tavern was the closest with any class to the docks. On arrival they discovered it to be congested with colonial sealers, Americans and French sailors and divided into three distinct factions. An air of hostility prevailed and it would only take one spark of nationalism to set the establishment ablaze.

It was the local sealers who appeared most displeased as they had been in Bass Strait, a stretch of water between the main land and Van Diemen’s Land, where there had been almost war with the Americans. Each blamed the other and after a death on both sides a simple truce was obtained with the American ship, being the first to reach Flinders Island, claiming the best sealing grounds.

While displeasure was building between the American and Colonial sealers, a nervous peace prevailed within the tavern, with the French chatting in language at a discreet distance. Sam and Edward entered into the electrified atmosphere and found a quiet corner away from all three opponents.

Who threw the first fist was unclear, some blamed the Colonial’s other assured it was the Americans but a scrap commenced between two burly seamen from opposing sides, most were prepared to allow it to continue as entertainment, even taking bets from the sideline but as often in a tavern brawl, if one obtains the upper hand another joins the affray to defend the looser.

What started an all in brawl was a line in French from one of the Amities crew, “Vive la Republique Francaise!” It was enough, the Americans loved it, the Colonialists didn’t understand it but knew well its connotation and came at the French with whatever was at hand, then on the third side came the Americans, all three groups going it at each other regardless of who they attacked, French against Americans, Americans against Colonialists, all regardless of country, creed or nationality. Soon three nations of blood commenced to discolour the tavern floor.

As a French sailor shouted, “Vive la Francaise,” it became too much for Edward and was prepared to defend the honour of his father. His muscles tensed with fists clenched and soon out of his chair to join the affray. His arse had barely left his seat before Sam grabbed him by the arm. “No!” he shouted close by the lad’s ear and pulled him back, “best we be gone from here, if they catch you in a mêlée your ticket of leave will be cancelled and you will be back on the road gangs, or worse.”

“But!”

“But nothing,” the farmer growled and dragged the lad from the bar. At that very moment a troop of soldiers hastily entered.

Towards evening both captains were called before Macquarie, who with much deliberation decided to send them back to their ships, issuing fines for affray, knowing only too well once back on the high sea nothing would be done about it and seeing both countries, America and France, were supposedly at war with England, nothing could be done there either. Macquarie did give the captains escort to their vessels making sure all of Sydney knew of their failings, being marched within the ranks of the regiment down Loftus Street to the docks. As they travelled they were jeered by the gathering crowd, with both the farmer and Edward silently in attendance.

“I believe I should thank you for stopping me,” Edward expressed as the soldiers passed with the sea captains en route to Government House and news came of the many arrests of colonials involved in the fracas.

“Think nothing of it, more for me than you,” the farmer gave reason, “with you back in irons then who’s complaining would I have to contend with.”

“Do I really complain so much?”

“Na you’re alright kid but how about returning for that second drink we didn’t get to finish.”

“Not Rosie Craddock’s,”

“Most definitely not at Rosie’s, I know her too well and she would have us working on the mess.”

“And Sam, I still don’t like the French.”

“What about the American’s?”

“I guess in some way they are cousins of sorts.”

“Possibly one day there will be peace, with both England and America realising that very sentiment,” the farmer concluded.

Later that evening with the changing tide, firstly the Charles slipped its moorings and was quickly down harbour and through the heads before anyone had realised it had gone. A short time later the Amities also departed and without lights burning soon passed through the heads in a southern direction, for exploration in Bass Straight to the south of New Holland.

Sam and Edward with their supplies were homeward bound with intention to bed down at their usual halfway inn at Liberty Plains. Arriving sometime after sundown found the inn to be somewhat full.

“Sorry we only have one room vacant but I could bring you a cot for young Edward,” Martha Smithing, the licensee apologised.

“That would be fine,” the farmer agreed as they entered into their room. Martha departed to find the cot.

“We could use the same bed,” Edward suggested.

“That we could but what would folk think?”

“We’ve done so before,”

“True but we are in company,” the farmer released a nervous and uncharacteristic chortle.

“Guilt’s a funny thing,” Edward humorously suggested, his blue eyes flashing mischief.

“I don’t feel guilt, besides there is nothing to be guilty of.”

“Except our thoughts Sam?”

“Not even those.”

“I’m afraid I’m not so innocent, I imagine James in my bed most nights and often when you and I share the bed.”

“For warmth,” the farmer lightly interjected.

“Yes for warmth but I often fear I will dream you are he.”

The farmer laughed; “maybe I should be James for a night so you can clear your frustration.”

Martha returned with her husband carrying the cot, setting it in one corner he departed for the bar.

“There you go lad, should be comfy enough.” Martha suggested while adding bedding to the cot.

“I’m sure it will be and thank you.”

“Well look at you and now a freed man,” she approached Edward, remembering that first night she had seen him chained like some wild animal to the farmer’s cart.

“True in part Martha.”

“I remember your first night here and it seems only like it was yesterday.”

“And I your kindness,” Edward answered in appreciation.

“Rubbish it was mostly Sam’s doing, he was concerned if he removed your bonds you would attempt something silly.” Martha finished making Edward’s bed.

“It was on my mind but as Sam said there wasn’t anywhere to go.”

“There you are, nice and comfortable, I’ll wish you a goodnight; will you be wanting an early breakfast?”

“That would be fine thank you Martha,” Sam agreed.

Martha left the room and closed the door.

“Did you mean what you suggested?” Edward asked.

“What suggestion would that be?”

“Don’t act dumb Sam it’s not becoming of you.”

“Anytime lad but I will never make the first move, I promise you that and even if you were to do so, I would first have to warn you on what you were entering into.”

Edward bounced up and down on the cot, “comfy enough.”

“You can have the bed and I’ll have the cot,” the farmer offered.

“Na an old bloke like you needs his comfort.”

“Old!”

“Well old compared with me.”

“Nine years you cheeky little imp.”

“No really Sam you are taller than I, you wouldn’t fit into the cot.”

“Do you really think I’m old, sometimes I feel so.”

“You’re fine Sam but are you fishing for complements?”

“Of course not!”

Edward stood by and cast his eyes over the farmer.

“You’ve got all your teeth.”

“That I have,”

“Good head of hair almost blond, dirty blond I’d call it.”

“What colour is James’ hair?” the farmer asked.

“Henna, yes most definitely red.” Again the lad cast his eyes over the farmer’s form.

“Some wrinkles; crow’s feet around the eyes.”

“It’s this wicked sun down here, dries everything out.”

“I’m getting them as well,” the lad admitted.

“Ocean blue eyes,”

“A good straight, strong physique,”

“Broad shoulders, strong arms, good legs.”

“I’m not a flaming horse to be bought you know,” the farmer growled while attempting to further impress his pose.

“If you were Sam, I would certainly buy you and put you to work.”

“Doing what?”

“Ploughing fields,” Edward gave a cheeky grin.

“Ploughing whose field?”

“Ah that would be telling.”

“Are there any other complements on offer?” the farmer asked.

“Well maybe but something that big should be kept to one’s self.”

“Ya cheeky young pup;”

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,222 views