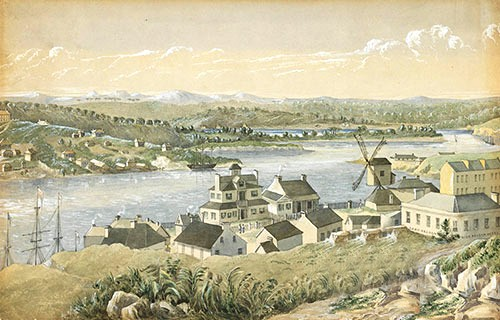

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 1 Apr 2019

It was a freed man who returned to Parramatta but Edward felt little different. He attempted to come to terms with it all, often retrieving his ticket of leave from its keeping on the over-mantle, neatly folded into a leather pouch smelling of leather oil and tobacco leaf.

Slowly he would read each word aloud, stumbling over the more technical terminology and words with more syllables that appeared warranted but his ability was improving with each lesion from the farmer, while Sam listened to his rendition with pride, sometimes humoured as he stumbled over pronunciation and teasing his correction.

Once Edward had completed he would read the deed of grant for a thousand acres of his selection and wonder what he would, or could, make of such a gift. Supposing it to be more a trinket that something of use, reasoning being he owned a thousand acres he wasn’t technically permitted to visit or farm.

What Edward knew of farming in New South Wales was limited to working on Sam’s patch, even less of animal husbandry. Back home it was simple, summer and spring the stock were in the paddock, winter they were inside. Locally it was a matter of letting the animals roam free with hope they could be found come time to muster, while trusting not too many fell to native spears, or duffing, as some bolters and less honest landholders were most apt at altering brands or running off with clean skin cattle to wear their own branding. As for wool that was a complete unknown field except for the few sheep Sam kept for the slaughter and how did one brand one’s ownership onto sheep. Asking the question from one working for Macarthur he felt somewhat silly with the reply. Ear marks of course, why you didn’t think they were marked with a branding iron like cattle did you?

During the lazy days when work had sapped his strength Edward would ponder on his journey across the mountains and what he had encountered, remembering the excitement displayed by the explorers as they discovered and named their prize and the disappointment Lawson had comically exhibited on missing naming rights. Yet it was Lawson who named Mount Banks, also he who penned name to Mount York, giving understanding Lawson was a modest man without feeling necessary to cover the ever developing map of the colony with his title or non-de-plume.

Spring was developing at its usual moderate pace with warm days and cool nights. Still cold enough to build a fire in the hearth and sit around its comforting glow until the early hours. Such was this night with Edward close to the fire’s comfort and the farmer close by, his eyes and thoughts on the lad. Edward lifted his head and noted the man’s interest.

“What?” Edward curiously enquired.

“What are you thinking as you appear to be far away.”

“I was thinking of James.”

“You really miss him true?” there was soft concern in the farmers tone.

“That is the truth of it Sam and I was trying to envisage where my correspondence would be and what James may be doing.”

“You letter would not yet be in England, that is a certainty.”

“I realise so,”

“It could be halfway around the Cape, or the Horn depending which route it takes, or if it comes to it, the ship could be trading with the Orient before heading home, that could expand some months to its progress.”

“Or at the bottom of the ocean,” Edward offered a depressing thought.

“Ships are improving by the year and have better charts; your letter will reach England I am sure of it, actually finding James that could be a different matter to consider.”

“You know what I really miss.” Edward gave a light sigh as a spark of wood fired across the earthen floor; he pushed the log towards the back with the toe of his boot.

“Go on,”

“Snow, I miss the cold crisp mornings when the snow is thick on the ground and the sky clear with only a slight warming as the sun clings low to the horizon.”

“Where I came from we didn’t have snow every year,” Sam admitted.

“We did in Devon and back then I thought nothing of it, now I pine for it.”

“I guess like most things we don’t miss them until they are no longer there.”

“I suppose so. Did you know it sometimes snows up in the mountains at Katoomba?” Edward alleged.

“Go on – did you see it?”

“No it was our native guide, he told me, at a place they call Katoomba close to three monoliths and Wentworth’s so named falls.”

“I think I would like to see this Katoomba.”

“It is rugged but most spectacular.”

“Yes I believe it would be a wonderful sight.”

The fire died down and Edward strategically placed another log towards the back. “Have you ever been in love Sam?” he asked without lifting his gaze from the dancing devils along the burning log, they appeared to chase each other along the wood in quick succession, flaring and dying flaring and dying until eventually they turned into one single flame throwing out more heat than was needed. Edward shielded his face and moved away.

“It has taken you a long time to ask me that question young fellow.” The farmer incidentally answered.

“Sorry it was rude of me to do so,” Edward apologised.

“No don’t be, the question is fair and as my servant I would not have answered but as a friend and colleague, yes I have been smitten on a number of occasions but never had the opportunity to do anything about it,” the farmer paused, “in truth I am in love now and with you,” for a moment there was an uneasy silence as the question hung in the air while searching for someone to answer. It came from the farmer, “don’t be concerned it isn’t the love you have for your James and could never be that, although it was your look that drew me to choosing you when you come from the ship but I suppose that was more lust than any other emotion. It is for your company, your fellowship I now value.”

“Oh I don’t know how to answer.”

“Then don’t and forget I even mentioned so, as it was wrong of me to place such a burden on your young mind.”

“Sam I would couple with you and enjoy doing so but it could never be the same as I feel for James.”

“Nor I Edward and I really pray one day you will find your James.”

“Thank you Sam and I appreciate your honesty and believe it or not, I know it has brought our souls closer together.

“I had a close friend once.” Sam admitted and now it was the farmer’s turn to drift away into his past.

“Who was that?”

“His name was Rowan, nothing like what you feel for James as we didn’t have the opportunity to develop that way.”

“What happened?”

“He was drunk one afternoon and took the king’s shilling.”

“He joined the navy?” Edward asked.

“Joined is somewhat of an anachronism, more like press-ganged and after only three days at sea he was killed by shot from Spanish cannon.”

“I shouldn’t have asked.”

“No really, I’m alright with it all. It’s a long time now, besides I was arrested but a short time later, so nothing would have come of it,” Sam weakly smiled, “unlike yourself, I don’t have to wonder if someone is doing fine back home.

“I suppose we all have our grief.”

“Well lad I’ll leave you with your fire, I’m off to bed.”

“Sam,”

“Yes Edward,”

“Can I sleep with you tonight?”

“Any time it pleases you to do so.”

While working in the top paddock removing large stones to the fence line in preparation for ploughing, Edward lifted his head to spy a small group of aboriginal woman digging close to the edge of the farm proper. There were at least six women and one young man, possibly in his mid teenage years, possibly younger. As Edward was unfamiliar with the look of the natives, he could not be positive but the black youth did appear to be of jolly mood.

The group was close enough for Edward to hear their conversation but being in language none meant anything to his ears. Out of courtesy Edward waved. The women ignored him, yet the young lad, with much animation returned the gesture, bringing the women to point and laugh at him, while giving what appeared to be mockery. One of the women called out to Edward and pointed to the black lad, Edward, not understanding their meaning, again waved back.

The women having found what they were digging for gathered their dilly baskets and departed. As they did so Sam came upon the scene, “what’s the commotion?” he asked. Edward explained what he had seen, “they are often there and I keep it free for their purpose.

“There was a lad with the women; you don’t usually see young men with the women while they are gathering,” Edward explained.

“True there is men’s work and there is women’s work and they are very traditional about that.”

“So why would this fellow be with the women, he is almost an adult.”

“Sistergirl I expect,” the farmer simply answered with some humour.

“Sistergirl, what is that?”

“Men who believe they are women trapped in a man’s body and there are also Brotherboys, being the opposite.”

“Oh,”

“Even the blacks have gender problems, did you believe us whites have all the fun.”

“I’ve never meet the such before black or white,” Edward appeared shocked, finding it difficult to comprehend gender confusion.”

“And I was watching from a distance, by the lad’s actions I believe he fancies you, so you better watch yourself.”

“Do they also have sodomites?” Edward asked.

“Couldn’t say but people are the same the world over black, white yellow. If you find a thief in one race you will also in another, so if people like, well yourself and me are as we are, I guess so be it with them.”

“Sam that is the first time you have admitted your sexuality.” Edward appeared most surprised.

“I thought I had been saying so without using words for yonks.”

“I guess so and I believe I’ve always known even before our little talk but with the blacks – well I suppose you are correct.”

“They are a happy lot,” Sam spoke of the native women.

“I don’t know much about them,” Edward admitted.

“Before you arrived I had a good rapport with the local mob but of late they have been somewhat absent – possibly gone walkabout, or some farmer or another has done them bad.”

“Is it possible my presence has frightened them away?”

“If that were to be true the women wouldn’t be digging and your boyfriend wouldn’t have acknowledged your wave.”

“Boyfriend Sam, I don’t think so.”

“I dunno’ Edward, by the way he was looking at you and his pleasure in returning your wave, I believe you have found a friend for life.”

“Shudder Sam, don’t even suggest such a thing.”

Spring had two weeks remaining and the weather was as if summer has long commenced. The usual spring rain had failed, although there had been the odd shower but little more. The crop in the field was struggling and each time there was a sprinkling it bolted on but without follow up rain it was starting to go straight to seed without properly cobbing.

It was a lazy afternoon and Edward had completed carting water for the vegetable garden when the farmer called him to cast his eyes towards the road and that of a traveller coming their way. Eventually the traveller could be recognized as Scruff Langford being one of Edward’s associates when they crossed the mountains and one who was once bound over to the Blaxland property.

The man arrived and was offered refreshments. As Edward obliged him with a meal he realised he had no idea of the man’s proper name. Scruff was fine within the ranks of convict servants as it mattered not if you had a name or not, like some animal any name would suffice being so to depict one poor wretch from some other.

“Why young Edward, ‘tis Tibias Robinson Langford but Toby will do and I’m so accustomed to Scruff it would also be accepted.”

“I can’t keep calling you Scruff,” Edward admitted.

“Then Toby will suffice.” And Toby it became.

After freshly baked bread and a plate of mutton stew, washed down with hot black tea Scruff appeared satisfied and admitted so, declaring it was the finest meal he had enjoyed since leaving home.

“Where was home?” Edward enquired realising while travelling with the man, very little had been exchanged about their past.

“Christchurch, it is on the Solent in Dorset.”

“I have no knowledge of the place,” Edward admitted.

“Never mind, it was another lifetime and almost forgotten, I came out the third fleet and it was a right rotter, best left at that.”

“What are you doing out this way, the last I heard you were over Liverpool working for some fellow carting hay.”

“Was my boy but I have been offered a grand position more suited to my learning. Lady Macquarie wishes to develop a public garden and seeing I was once on the gardening staff at Marlborough House in London, the Governor suggested me.”

“Nice work if you can get it,” the farmer appeared most impressed.

“Yes I’m looking forward to the opportunity but that isn’t the reason I detoured this way to visit you.”

“Whatever the reason you are always welcome,” Edward genuinely admitted.

“Maybe not so when I explain, as our friend the Blacksmith has left Newcastle and is back in Liverpool and asking after you. It is only time before someone supplies your position.”

“Oh,” Edward exclaimed as past fears returned to haunt him. He took a deep breath and cast his gaze towards the farmer but there was little Sam could do except offer support if the occasion should arise.

“Still I wouldn’t be too concerned, he is mostly drunk but all the same I thought you should know, as for some strange and unknown reason he is eaten up with some unrelenting hatred.”

“I thank you Toby at least I will know to watch my guard. Would you like to stay the night?”

“Appreciated you fella’ but I should be going, there is a boat down river from Parramatta late this afternoon, a brisk walk back to town should give me time to meet it.”

“Would you like me to ready the cart and run you into town?” the farmer offered.

“Again thank you but no, I am apt in walking and enjoy searching through the scrub as I go for new species, can’t do so from a cart or horseback.”

With their visitor departed the farmer became concerned towards Edward’s state of mind, after receiving such information on the blacksmith. Oddly the lad appeared to settle into the situation with an amount of devil may care. He was no longer under the control of Government regulations as a convict and no longer felt the stain of his crime, as for the blacksmith, he was a big man and violent but had a small mind, bringing Edward to consider brain could and would succumb brawn.

“It appears this fellow has developed a most unhealthy attitude towards you as it isn’t natural for a normal person to continue on for such an extended period,” the farmer concerned.

“That was partially my own doing.” Edward gave a nervous laugh.

“How so?”

“After being raped by the blacksmith I became protected by an even larger man who threatened the blacksmith with more violence than he could render,” Edward gave a shudder and continued, “it appeared the guards knew of my crime with hope I would suffer in the same way and turned their eyes, or encouraged my treatment as their entertainment, even as far as forming a circle and clapping it on.

“What of your benefactor?”

“I wouldn’t call him so; he also raped me but was less violent and lacked the sexual urges of the blacksmith, so the invasions were less frequent but from then on the blacksmith threatened to have his revenge.”

“So for almost a month while with him crossing the mountains the man failed to recognise you?” Sam asked finding it difficult understanding how that could be so.

“That was most fortunate, I can only think he is so dim-witted he lacked the ability to do so and the lighting below deck was poor, while my body was in such disarray again seeing me clean and fit I think he had difficulty in doing so, also few words passed between us, mostly him grunting his pleasure and me silently wishing him away. Another fortune, with my new protector I was to go above deck at different intervals than Ingles and was assigned to a different section of the ship.”

It was more than obvious over the following days after the visit from Scruff, Edward was carrying anxiety born from the information. Slowly he settled and the frail crop became a more immediate concern. Much of his daylight hours involved in water cartage for the vegetable garden and what little they could carry to the field but without real rain that was destined to fail.

Fortunately with the warm spring weather and the creek water the vegetable garden was flourishing and with ample produce there were many visits to the Parramatta market, even times when some of the surplus was transported down river to Sydney Town, so the poor crop became secondary.

While weeding amongst a number of cabbage rows the farmer was found standing while shading his eyes from the midday glare and quietly gazing towards the cloudless south east sky. Edward called and Sam lowered his arm, “I thought I saw the signs of clouds on the horizon,” he hopefully suggested.

“A nice thought Sam but I don’t think it will ever rain again.”

“You therefore wouldn’t know about the summer of 0’nine?”

“True I wasn’t here – what happened?”

“There was a dry like this then the rain came, almost a disaster.” The farmer once again stood and pointed towards the tree line at the edge of his ploughed field, “the women are back.”

“What about the rain in 0’nine?”

“It almost destroyed everything along the Nepean.”

Edward interrupted his work and watched as the women commenced to travel towards the crop but on a line that would take them beyond the creek.

“Your boyfriend is with them,” The farmer teased. Edward gave an ironic chortle and came to the farmer’s side.

“Do you think he’s -” The lad failed to complete his question.

“Is what Edward,” the farmer was still teasing.

“You know,”

“Edward I don’t know but am guessing you mean attracted to men. What I’ve heard from others is the Sistergirl is a woman trapped in a man’s body. I don’t believe they are as you are inferring but if they think they are female then it is reasonable to suppose they would fancy men.”

As the women came close to where the two were working, one bent down and helped herself to a large full cabbage and quickly tucked it under her arm, “that’s right girls, you take the best,” the farmer pleasantly called.

“Should I stop them?” Edward suggested although appearing little interested in doing so.

“No there is plenty for all and I hear they are doing it badly this year and we have taking their best land.”

“But they don’t farm,” Edward complained taking on one of the aspirations that made up Terra Nullius.

“Not like we farm but they do in their own way, they encourage their tubers to grow and look after medicine plants, also burn of the late summer grass to encourage new growth for kangaroos.”

“I suppose that could be considered moderate farming,” Edward half heartedly agreed.

“Either it is or not, and they do fish farming.”

“What they round them up with dogfish,” Edward laughed.

“No they make fish traps and keep their catch alive in pools until needed,” the farmer stressed as another large cabbage left the soil. On doing so the women looked back and laughed while the young lad, the so named Sistergirl, approached towards Edward and once within an accepted distance spoke in language.

“I don’t understand.” Edward complained as the women commenced to laugh and point at the lad.

“Bahloo like Gubba.” The youth spoke in broken English, he then pointed at Edward and without further word returned to join with the women who were now crossing towards the creek.

“What was that all about?” Edward confusingly asked Sam.

The farmer laughed.

“What?”

“It’s obvious isn’t it?” Sam remained humoured by the transaction.

“To you possibly,”

“He is saying he likes you.”

“How do you know that?”

“Obviously his name is Bahloo and like is like in any language and you are Gubba.”

“Gubba – what in hell’s name is Gubba?”

More humour from the farmer.

“You’re enjoying this aren’t you Mr. Wilcox?”

“Slightly,”

“Again what in the name of damnation is a Gubba?” Edward repeated with a frustrated growl.

“The word Gubba is Government but they can’t say it and over the years it has become their word for all white men.”

“Smarty, how do you know that?”

“I’ve been here a good ten years more than you Edward and I make it my business to learn things.”

“I think I’ll keep away from that fellow, likely to end up with a spear in my back; or something unwanted elsewhere,” Edward gave a shudder and returned to his weeding.

“If you were to touch the women more than likely that could be the outcome but your friend Bahloo would be fair game.”

“I don’t think so and I’m not that desperate, besides it wouldn’t be right.”

“Why not Edward,” the farmer remained enjoying his friend’s discomfort.

“It would be hypocritical of me to take advantage of a savage.”

“Edward get one thing straight, they aren’t savages.”

“I digress, it wouldn’t be right to take advantage of a native.”

“I thought god was colour-blind,” Sam remained mused.

“I’m not religious,”

“No but I think you are a little anti-black.”

For a time Edward fell silent as Sam’s perception of his character filtered through to his subconscious and he weighed the reality of it all. He wasn’t against the blacks he was positive of that but he was still somewhat frightened by them. Eventually he answered.

“I do hate the French.”

“What brought this on?”

“What you said about me being against the blacks,” Edward said.

“You do appear that way.”

“To be honest Sam more frightened of them than against them.”

“At least you are honest. Tell you what, it appears this young fellow wishes to get to know you. Do so and you could be surprised.”

“What take him to the cot?”

“No Edward you can befriend him without all that.”

“Umm,”

“At least talk to him, it may make it easier for both of us living so close to their camp,” Sam suggested.

“Again umm,”

At dusk that evening a neighbour Jeremiah Sneddon arrived at the farmer’s door, complaining of the thieving blacks. They had not only stole vegetables and after shooting at them without the desired result, he had obtained two savage dogs to patrol his garden but that very morning as he visited his fields he found the dogs, both dead with spear wounds and much damage to his crop.

“Humour them Mr. Sneddon, they are like children and if you allow them to have some of the crop, in general they will leave you be.” The farmer advised while attempting to remove the angry sting from the man’s tone.”

“Given half a chance I’ll do more than that. What is needed is for local farmers along the branch to gather our strength and move them from the area, shoot them if necessary like the vermin they are, I believe poisoned flour worked on the Hawkesbury.”

“I am sorry Mr. Sneddon I cannot be party to that,” the farmer warned as Sneddon turned to Edward for support.

“Nor I Mr. Sneddon, as Mr. Wilcox has stated, let them have some and they will leave the rest, we find it works.”

With Edward’s refusal the man stormed from the hut and could be heard cursing all hell from as far as the gate.

“I think we are heading for an all out war with that man’s intention,” the farmer gravely warned.

“Should we do something, possibly warn the constable in Parramatta?”

“Doing so would be useless; it was Constable O’Brien’s exploit with the poison flour on the Hawkesbury and now he is Chief Constable at Parramatta and I don’t think he has improved his interracial stance since being promoted.”

The next evening at dusk shots were heard from the Sneddon property, moments later a group of five natives came running across the farmer’s land, one appeared to be favouring an injured leg but still had enough in him to keep up with the others, while carrying what appeared to be a small axe.

On this occasion the natives passed close to the hut and it was obvious the injured man was bleeding profusely from his upper thigh. Wilcox called for Edward and they went inside closing the door, believing it wise not to be seen as party to their neighbour’s activity, while Edward remained vigilant from the window.

All was quiet until early morning and again shooting was heard and on observation a fire was noticed coming from the direction of Sneddon’s farm. The natives had set fire to the crop and by all accounts had spread and Sneddon’s hut was in flames, again the natives came at speed across the farmer’s land to disappear into the tall timber towards the branch creek.

Early afternoon Sneddon arrived with his cart loaded with what possessions he had saved. “That’s it,” the man shouted from his cart without alighting, “I’ve had it, they have burned me out, I’m returning to Sydney.”

“I am sorry Mr. Sneddon but it was too late to help by the time we noticed the fire,” the farmer weakly apologised.

“The bloody drought and blacks, this flaming country isn’t worth a pinch of shit,” Sneddon shouted as he guided his cart away.

During the following day the native women returned and although making their way through the vegetable garden towards the creek, they didn’t pilfer any of the vegetables. It appeared to be the women’s way of saying they did not hold either Edward of Sam responsible for the actions of their neighbour.

With the woman came Bahloo, in passing he broke away from the women coming to stand before Edward.

“It not Bahloo – whoosh,” he spoke apologetically while raising his hand in a lifting gesture.

“Whoosh Bahloo?” Edward asked not understanding the lad’s meaning.

“Bahloo is telling you he had nothing to do with the fire,” the farmer explained. Edward smiled and nodded his head.

“Bahloo like little Gubba, no hurt Gubba,” the lad promised and quickly departed to rejoin with the women.

“I will say one thing Edward, it is better to have them on side than against, even if the lad wants it away with you,” the farmer advocated, displaying a lighter side to the situation.

“That I can do without, where do you think he learnt some English?”

“There’s a church school along the way towards Parramatta, he may have picked it up there as the reverend likes to teach the natives, wants to make little black Christians of them,” Sam suggested.

“So they can learn other languages?” Edward had not yet come to fully understand they were only people and not two headed monsters.

“Edward you are again showing your ignorance.” Sam admonished his friend’s shallow conviction.

“Point taken but as a boy my da told me about cannibals and I’m having trouble dislodging it all.”

“Inside one’s head is the little boy, the youth, the young man the adult and they are all there waiting for their opportunity to surface and display their own opinion.”

“What does that mean?” Edward asked.

“It means you are a man now and should be capable of sifting through the opinions of the past and make rational decisions.”

Towards the end of the week the women, with Bahloo close at heel, returned from somewhere down the branch creek and the direction of the burnt out Sneddon farm. This time Sam met them and gave a good supply of produce. As the women departed towards the tall eucalypts Bahloo about turned and came to stand close to where Edward was working. The lad didn’t speak, instead appeared satisfied in watching Edward as he weeded the patch.

“I notice your friend’s back,” the farmer called.

“And don’t you dare leave me alone with him,” Edward growled as the black lad came close and pointed at the weeds.”

“They are weeds Bahloo,” Edward explained.

“Wedz,” the black lad answered, “No weeds.”

“Weeds,” the lad parroted, elongating the vowels.

“That’s right weeds,” with Edward’s word the lad bent and commenced to pull out a carrot. Edward quickly prevented him from doing so, “no that is a carrot,” Edward again pointed to the weeds, “that’s a weed that is a carrot,” and with that he plucked the carrot from the ground, whipped away the dirt, he took a bite, “carrot food not weed.”

The lad appeared to understand and said; “arrot,”

“Carrot,” Edward corrected and the lad mimicked the word with perfection.

“You Bahloo,” Edward pointed at the black lad’s uninitiated chest while keeping his eyes from the rest of his naked body, Edward then place the same finger on his own chest, “Me Edward.”

“Edwa,”

“Edward,”

“Edwa,”

“Alright then Edwa – that will do, I rather like that.”

“Bahloo like Edwa,” the lad broke into a cheeky grin.

“Maybe Bahloo does like Edwa but not like the way you wish.”

“Wish?’

“Never mind, let us try something else. Edward commenced to point at things and relate their names, the lad repeated the words and where possible gave the native equivalent for the same object. It was obvious he was a quick learner and retained the words freely surprising Edward. While teaching Bahloo English another thought came, that being it wouldn’t hurt Edward to learn his language at the same time.

Over the following week Bahloo arrived like clockwork. He would stand at distance until Edward waved him on, then like an excited child would quickly come to his side and resite the words he had learned the previous day. Often the women while crossing the farm and seeing Bahloo talking with Edward would point and laugh, calling in language which made Bahloo laugh even louder but as for their menfolk they kept to the grassland towards the hills where the game was more plentiful but with the drying they needed to go further afield and remain away for longer periods.

Towards the end of that month the farm received a visit from the Parramatta police in the person of Chief Constable Pat O’Brien asking questions on the destruction of the Sneddon property.

Sam met the man at the door with Edward working in the field. On noticing the policeman’s visit, Edward slowly approached.

“Mr. Wilcox, would it be?” the Constable roughly greeted as Edward reached the hut, the policeman suspiciously eyeing the lad as he came to the farmer’s side.

“It is Mr. O’Brien and what brings you out this way?” the farmer enquired knowing well the policeman’s intent.

“The Sneddon property, I believe the blacks burned him out?”

“I think not Mr. O’Brien I believe it was a bushfire, to my knowledge there’s been no problem with the blacks this way.”

“Mr. Sneddon has reported they came at night, killed his dogs and stole from him, that he shot and wounded one of the buggers and they returned the following night and set fire to his crop.” The Constable appeared somewhat indifferent needing to refer to written note he kept in his pocket and even then was troubled in reading what he had penned.

“True there was some shooting but I believed it was aimed at wild dogs,” the farmer then addressed Edward, “wild dogs wasn’t it Edward?”

“I believe so Mr. Wilcox.”

“In my opinion the lot should be done away with, like along the Hawkesbury,” O’Brien suggested.

“Poison, wasn’t it Mr. O’Brien?” the farmer calmly reiterated his belief.

“Rat poison I believe Mr. Wilcox, can’t help it if they are so stupid they took what was laid for vermin.”

“And a nasty way to die, I’ve seen the agony it causes in animals that have innocently taken it.”

“Possibly so but one can’t help stupidity, one more item of interest Mr. Wilcox,” the constable spoke, his eyes resting on Edward but seeing only the lad’s past conviction.

“Yes,”

“No possibly two, firstly that servant of yours,” still the man’s eyes remained on Edward, while speaking as if Edward wasn’t present, “he appears to act a little too cocky for one bound over.”

“Edward has been given a ticket of leave and in person by the governor himself. Do you wish to see his papers?”

“I think not, still he has his term to serve, of that I am certain.”

“Edward knows what is expected of him Mr. O’Brien.”

The constable’s eyes dropped from the lad and burnt deeply into those of the farmer, “second point Mr. Wilcox I believe you have been giving the savages free range across your plot?”

“That I do as the Government Gazette demands.”

“Possibly it does but it’s the likes of you who are making it difficult for us all – putting that aside for the present, do you know your west divide neighbours?”

“Only by sight he isn’t a sociable character.”

“Finally have you had word of an illegal still?”

The farmer was growing tied of the constable’s questioning, with his his down-putting attitude and although he had heard of such a still, also the approximation of its whereabouts, he refused to say so.

“No, Mr. O’Brian and it was only last week your superiors in the military came by asking that very question and as I informed them, I have no knowledge of the still.”

“What about you lad?”

“No sir, I don’t leave the farm without Mr. Wilcox’s knowledge.”

“You do realise distilling is a capital offence?”

“That I do,”

“Umm,”

The constable stood for some time without speaking, his eyes past the farmer into the interior of the hut, then around the immediate vicinity of the hut but could not find anything of interest. Eventually he spoke, “once again I warn you of your leniency towards the blacks, the establishment holds a dim view of handouts, there’s not enough food for us as it is.”

The farmer gave a slight nondescript nod but remained reticent.

“Very well I will be on my way, there are others I need to interview on the matter but if you have trouble, be sure to let me know.” The Constable put away his notes, gave a final nod to the farmer, another suspicious glance towards Edward and remounting his horse was gone.

“You should warn your mate to let the others know not to accept flour or food from anyone for a time,”

“Yes I will do that,”

“So what do you think of our Chief Constable, Edward?” Sam asked.

“Like you, I would have also withheld certain knowledge of that illegal still.

“Ah you are learning how to survive, best to know nothing about nothing and say the same.”

“Do you think there will be any repercussion over Sneddon’s farm?” Edward asked.

“I don’t believe so, he was recent to the area, it is my opinion he hadn’t time to gather support from any of the neighbours but O’Brien is another matter, he may try his little trick from the Hawkesbury on the local natives that is why I suggested letting your mate Bahloo know about not accepting food from anyone.”

“Was the poisoning at the Hawkesbury bad?”

“It depends on what you interpretation of bad happens to be. If you consider a dozen or more dead and left to rot beside the river as bad, then that it was.” Sam drew a long breath, “there were repercussions and a number of innocent settlers, women and children succumb to retaliation a short time after and there Edward lays the dilemma, it is always the innocent who suffer in a time of strife.”

Edward found no difficulty explaining to Bahloo about the chance of poisoned food as the lad had, as Sam once suggested, received some schooling when he was a boy at the church school near Parramatta and there learned of the poisoned flour. His clan also had knowledge of it and although they believed safe to steal from a farmer’s patch, would not accept hand outs from strangers.

Often Edward would spy Bahloo fishing on the branch creek in his bark canoe, observing how simple it appeared with his two ply line from the bark of Cabbage and Kurrajong trees, its stone gna’mmul sinkers and hooks from the turban shell. With ease the lad would catch a fish, almost as if willing it onto his line, while feeling even a brush past of a fish’s wake and with a quick tug it was caught and into the canoe.

This morning Bahloo had much success with his fishing and brought a large specimen as a gift for Edward but wouldn’t come to the hut, instead calling from some distance.

“Edwa,” he called while Edward was having his breakfast.

“Your mate is calling for you,” Sam smiled while serving porridge, sweetened with a little wild honey that Bahloo had brought as a gift some time earlier.

“Well aren’t you going to see what he wants?”

“I guess so.”

Once outside Edward noticed the fish, “what have you there?”

“It fish for Edwa,” the lad answered in his broken English, holding it high for observation.

“And a very nice one at that, Edwa could never catch a fish as grand as that one.”

“Bahloo show you.”

“Would you Bahloo, would you show Edwa how to fish?”

“I show you blackfella’ way.”

“I would like that.”

Two mornings later the lad was back shouting Edward’s name from his stand amongst the cabbages. Edward answered and approached.

“Edwa come with Bahloo, I show you how to fish blackfella’ way.”

“Later, I have watering to do,” Edward answered as the lad’s expression turned from light-hearted to disappointment.

“Go on Edward, I’ll finish up here, you may catch us some supper,” Sam enforced.

“Are you sure?”

“Go on, don’t disappoint the lad.”

Once at the water Bahloo sprung into his canoe with ease while Edward almost toppled it and them both into the water. Quickly Bahloo demonstrated the correct procedure and Edward again attempted with moderate success.

Away from the bank Bahloo soon produced his line and loaded the shell hook with some large white grub he had extracted from beneath tree bark. “Now Bahloo show Edwa,” quickly he dropped his line over the canoe’s side and almost as quickly it came up with a fair size river fish. The lad rebaited the hook and passed it to Edward, “now Edwa catch fish.” Edward followed the lad’s casting and moments later a tug and the bait was gone. Again the line was baited and again the bait became a fish’s meal.

“You fish Bahloo, Edwa watch,” Edward forcefully handed the line back to the lad.

“Edwa no want to fish?”

“Edwa no blackfella’ eh Bahloo, I watch you fish.”

“I catch Edwa plenty fish.”

Soon the lad had the fish biting as much as the mosquitos were enjoying Edward’s blood and within half an hour Bahloo gave up the fishing. “Best leave some for next time eh,” He said and wound in his line.

Back at the bank the lad offered Edward half his catch but Edward took only two and thanked Bahloo for the fish and experience.

“Edwa go fishing again tomorrow.” Bahloo offered.

“Yes soon Bahloo but not tomorrow.”

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,223 views