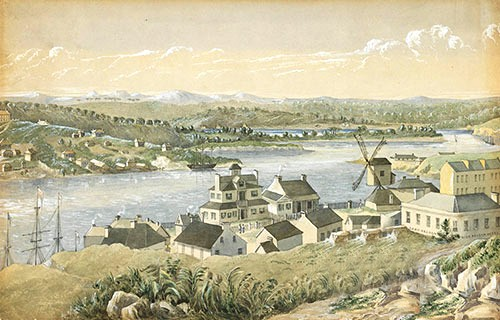

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 25 Mar 2019

On returning to the Wilcox farm Edward was much surprised to discover how quickly the spring weather brought on the new crop but his surprise was weakened by his experience and quietness was forthcoming as he reflected on a most unwelcomed reunion with the blacksmith.

After the third day without sign of his usual exuberance, the farmer found it necessary to enquire on the lad’s wellbeing.

“Nothing I can’t handle Mr. Wilcox,” the lad answered from somewhere deep in his troubled thoughts.

“Not true Edward I know you well enough to realise when you are worried, didn’t it go well on your journey?”

“Yes Mr. Blaxland was most admirable, as were Mr’s Wentworth and Lawson.”

“Then where did this quiet come from?”

Edward returned to his thoughts and at first was reluctant to answer as being robbed of one’s dignity becomes most personal, beyond that it holds a great measure of embarrassment to think he was so weak he could not protect against such an attack. Besides was he not guilty and proven of being so by the law of his land, did a small portion of his psyche cry out for such treatment? If it had been James he would have pleasurably surrendered his person, possibly even with the farmer but such an ugly animal of a man was not and would not be canvassed for.

Eventually he reluctantly conceded. “I suppose I should confide in you Mr. Wilcox.”

“Suppose Edward, I find that somewhat discourteous, after all this time you should know you can confide in me on any matter.”

“It was one of the servants, Tom Ingles,” Edward paused.

“Go on,”

“He was on the Duchess of Devonshire and remembered me; he was also one of the prisoners who forced me into having sex with them on the ship.”

Edward drew in a deep breath, “he raped me again on the last day of the crossing and forced me further on our return or he would do me harm and tell the others of my guilt.”

“Did he do so?”

“I believe not as he threatened there would be more treatment if and when we met again. I guess it is his way to have his hold over me.”

“Edward such men should not be privileged to live, is he from the Parramatta area?”

“No he belongs on the Blaxland estate down Liverpool way and some distance thereafter.”

“Are you hurt?” the farmer enquired while displaying a high degree of concern.

“No only my pride and dignity.”

The farmer gave a wry smile, “we who are, or were convicts aren’t allowed the luxury of pride or dignity – but I guess it still remains just below the skin and sometimes even more strongly than a freed man.”

“I suppose but like I did after the passage on the Duchess, I will survive.”

It was then the farmer diverted from character, crossing the room he took the lad into arms and held him tight. It was a friendly hug without overtone, as one would convey when meeting family or close friend after a period of absence. “Edward I have come to love you like a brother. No more than that a soul mate and even more but that can never be. I hurt for your harm.”

Edward allowed the display without a flinch and sinking deeply into the emotion he cried. It was the first time since he was a child he had done so but his fears, his mistreatment his loss of all since taken from his home fell from him like autumn leaves, leaving the bare branches of reality for all to see, “I’ve sorry Mr. Wilcox,” he apologised, “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be lad and never call me mister again, or Samuel. To you it is Sam and in my mind and thoughts you are a free and honest man and that is to me worth much.”

Finding composure Edward sunk into his chair and gazed blankly at the evening’s fire. It was spring but still the nights held their coolness and the warmth of the fire made him feel alive. He in that moment had place disclosure on his past and oddly thought of his future and if Blaxland’s promise, given also by Macquarie, would eventuate. Would he receive a ticket of leave and become free?”

“May I enquire of what you found beyond the mountains?” the farmer cautiously enquired, giving the lad time to settle from his distress.

“Oh Sam it was most beautiful, wild and beautiful and dangerous, there were tall escarpments, waterfalls that tumbled a thousand feet into even deeper ravines and when at the western reach the land stretched forever into the sunset and beyond, green and flat with rivers ever flowing westward as far as the eye could see.” Edward then commenced to laugh.

“Why the humour young Edward?” the farmer asked.

“It was the explorers and their desires, all the while like excited children naming new discoveries, Wentworth named the tall falls with his own, Blaxland a mountain, then another mountain after Royal York and Mounts Boyce and Werong but poor begrudged Mister Lawson missed out and grumbled much about it.”

“While you were away I travelled into Parramatta and remembered to post your correspondence, there is an agent there now,” Edward displayed joy with the news, “don’t raise your hope too high, as I said it possibly could be over a year, even longer before you receive a reply, that is if the ship even makes it back to England at all, you have Napoleon annihilating Europe and trying his luck in the English Channel, even the Americans are at it with their attack on Canada.”

“I feel it will Sam, it must.”

“Then it must.”

It had been a dry autumn and crops suffered but the farm’s vegetable garden with water from the creek flourished and food was never scarce. During Edward’s absence the farmer had purchased a number of sheep so with the spring, lamb was served and as spring turned into summer it was mutton and salted meat.

Edward had been back at the farm for almost a month when a message arrived from Gregory Blaxland in the form of invitation from Government House, noting it would be the governor’s pleasure for Edward to travel to Sydney Town on the twenty-fifth of that month for audience with Governor Macquarie.

Fortunately the messenger from Blaxland was in the person of Scruff Langford and not the blacksmith, bringing a measure of relief to the lad but even so he found necessity to enquire after Ingles, while attempting to appear incidental in the asking.

“Mr. Blaxland got rid of him and a jolly job; sent him to Newcastle as they were in need of his trade there,” Scruff declared displaying a measure of relief. Edward thus let the matter lie, Newcastle was well distanced and nothing more than a coal mine and a prison for habitual criminals but soon the blacksmith, like Edward and Scruff, would have tickets of leave and chance to travel at will.

“You must wear good clothes to meet with the governor,” the farmer proudly suggested.

“Would it be proper as a convict to wear anything but what is issued?”

“Point taken but at least wear the new issue I was supplied for you at the government store in Parramatta.” The farmer quickly opened a large wooden chest at the corner of the room and extracted the convict uniform. This maybe the last time you need to wear these.”

“I have nothing else,” Edward realised as on arrival he had been stripped of his civilian clothing, by then but rags and was quickly dressed in the mustard strips of one bound over.

“If all goes to plan we will see what can be purchased in Sydney Town after visiting the governor, I have a little put aside for such occasions.”

“You should spend on yourself Sam.”

“I’m beyond trying to look presentable and little reason to do so.”

Edward released a happy laugh.

“That is the first time I’ve heard you laugh since your return.”

“I was thinking of home and Christmas presents.”

“You got presents?” there was surprise in the farmer’s tone.

“Not as such, there would be a new shirt and trousers for my older brother and he would hand his old clothes down to me, then I to William.”

“That is also the first time you have mentioned your brothers.”

“William was a year younger than I and Arthur almost two years older, so you can imagine how his clothes were ill-fitting on me; also a sister Margaret but she got new clothes and was married by the time I was deported.”

“You say your brother was and not is?”

“Is – but as I said once before about my father, it is best to consider them gone.”

It was the farmer’s decision as Edward had his appointment at Government House, they would made short holiday of the visit, staying overnight in Sydney Town, possibly an extra day and with the Governor’s grant of emancipation it would be celebrated with a few ales at Rosie’s tavern, even a slap-up meal, as Rosie was a grand cook and if the grant was not forthcoming then at least some enjoyment would be gained from the travel.

Wilcox had arranged for a neighbour to keep an eye out for bolters looking for easy pickings or a place to hide; besides there was little to be done, the crop was up and waiting for rain and the vegetable patch in preparation for the next planting, as for the few ewes, they had already lambed and measured for their chops.

The trip would also give the farmer opportunity to purchase more seed and if possible seed potatoes as there was great demand in the district for the product, although on the damper lowlands towards the sea they never amounted to much but in patches the ground was suitable for the planting.

Some distance out of Parramatta, where the Sydney road met with the river at a wide sweeping bend, they chanced upon a group of young men, or to be more accurate boys in their late teenage years swimming in the river and as naked as their birth, even with nude bathing being punishable by a number of strokes from the lash.

Carefree the lads were, shouting, splashing giving banter to one another in an accent that would be most strange to the ears of any visitor from the old country, with their g’day, how ya’ going and strange words like crikey and struth, being a mild forms of oath or surprise. Some were of local persuasion, others came from the visiting ships and previously unknown to the isolated colony.

“Currency,” the farmer simply announced with a pleasing smile as they passed, bringing Edward to enquire of his meaning.

“Such lads are called Currency, the word was coined; no jest intended, by the paymaster of the 73rd. regiment. They born to this land being Currency and a newcomer being Sterling, as the local money’s worth being less than that of England.”

“They appear a healthy lot and taller than those from home,” Edward gave a cheeky grin, “and quite naked.”

“Quite so,” with a quick flick of the reins the cart moved on, “the name Currency was supposed to be a slant against those born from convict parentage but instead it is worn as a badge of honour.”

Away from the river the farmer continued, “yes Edward I do acknowledge they are a handsome lot, strong and tall and most naked.”

“I notice their accents have also changed.” Edward admitted.

“As has yours lad, possibly even mine but we don’t hear the subtlety in our own voice. I guess distance and time changes all, yet no matter what you and I think, to them we will always be considered but Sterling and foreigners in their land, they are the future now and like the country watch them grow. This could advance to be the lucky country away from Europe and its wars.”

“You are somewhat a philosopher Sam.”

“No only representing what I see and feel, if you stand still long enough and listen, you can almost hear the colony bursting at its seams and wanting to break out, soon freemen will outnumber convicts and in doing so will demand the halt to transportation.”

“If I stand still too long, I think too much of home.”

“Only home my friend?”

“And more – always more;”

Late afternoon and close on Sydney Town brought about one extra comment from the farmer, being how quickly the settlement had grown and how many fine houses had been erected. The farmer had come to Port Jackson in his late teenage years and Sydney Town was but a scattering of bark huts and leaky tents, now ten years hence or little more, there were ordered streets, brick and stone houses, some with three floors and shops selling every conceivable product from every corner of the world but what surprised many a newcomer was the number of jewellery establishments with such fine silver, gold and gems and to a town with nowhere to wear such fine product.

It was often asked, why so many jewellery stores and simply answered, Sydney had become the fence for England’s burglaries. A gold and diamond necklace could be stolen in Mayfair, only to be found in the window of a Sydney shop. It maybe the best part of a year before surfacing but there it would be in all its valued glory and soon purchased by some good woman of the colony, who possibly only a year previous may have been a convict washerwomen, now well married to some free settler.

There was one such story of a much to do about town lady of quality, on leaving her entertainment at the London opera house, had a golden hair comb lifted from her well appointed head of hair. On visiting Sydney some years later, the very woman chanced upon her missing comb in a jewellery shop window. Her husband gave the proprietor two choices; supply the name of the fence or return the item. The store holder quickly, and without argument, returned the item.

Now at any given time there would be at least a dozen ships in harbour, many loaded with convicts from the old country, others brought strange accents and language from the Pacific Islands, China and Europe while it wasn’t rare to find a group of New Zealand Maori sailors, their faces heavily tattooed while performing some terrifying war dance down Pitt street towards grog stalls and taverns. In twenty years, as long as it took Currency to come of age, the convict dumping ground had advanced to become an international village of some developing importance towards South Pacific trading, an outpost of England with all its fears and prejudice.

It was decided as Edward’s appointment at Government House wasn’t until mid afternoon, they would take a room and refresh from their dusty journey before attending the appointment, besides the hot gritty day did dry out the throat of the most hardened traveller.

Once there were only rum joints scattered across the town, brought about by the rum trade of the Hunter, King and Bligh government years but Macquarie’s arrival changed that and banned the use of rum to pay for labour and goods, as too many drank their wages before purchasing food, then fell back on handouts from the government store. Now there were a healthy number of taverns with legal trade, soft beds and fair meals, as well as boisterous conversation for the weary traveller.

For convenience it would be Rosie Craddock’s but the farmer had his favourite tavern when he came to town, The Sailor’s Arms, possibly it was the secret smirk given whenever he entered, a thought kept close and never shared even with Edward but the farmer had once known a sailor. That was long ago, he was killed onboard the Repulse during a fight with the Spanish. Rowan Spinner and a cobbler’s son, press-ganged into the navy by accepting the king’s shilling. He sailed out of Sam’s life without even a farewell and into the channel with the sun at its zenith and a fair wind in the sail, when from a blind side came the single cannon shot that ended a short but building friendship.

Wilcox had become friendly with the publican, Maisie Bradshaw, known to most as Maz, originally from Sam’s own county and most bawdy without the simplest inkling of femininity. The women possessed a temper to match and strength of any man, being most necessary to keep the roughness of the dock area in check.

Maisie was married, her husband Lenny, a stick insect without character and much advanced in years in comparison, with a taste for cheap grog and younger women but seldom chanced his fondness for the latter but wasn’t slow in pinching the bottom of some barmaid when Maisie wasn’t about and if sanctioned oblige a little further.

Maisie had been transported as a young woman, with the mindset to make something out of her misfortune. She jumped at the chance of marriage to a freeman and no sooner had Lenny’s ring encircled her finger, than a metaphoric ring went through his nose. Now Lenny mostly kept to the back rooms cleaning and lifting barrels, while conducting himself in the manner expected of a well behaved husband.

At the gate of the Governor’s residence Edward walked boldly ahead of the farmer but was abruptly halted as he attempted to continue by a most officious guard who address his demands to Wilcox without a second glance towards the lad.

“I have a meeting with the Governor,” Edward protested.

The guard held his resistance with a well aimed bayonet pointed at the lad’s belly, “mind your manners convict.”

Wilcox stepped forward, “it is true sir the lad has been instructed by letter to have audience with the governor.” Wilcox withdrew the invitation and passed it to the guard. A quick glance and it was returned.

“To the main door and wait, there you will be instructed further.” The guard withdrew his bayonet’s threat and returned to his post, mumbling all the while of convicts and flaming emancipists giving more airs and graces than the landed gentry.

At the open door to the residence the two paused, “what now? No one appears to be around,” Edward nervously spoke, his head cranked beyond the recess of the open door.

“Manners Edward,”

Edward recoiled from the inner space.

“Knock I suppose,” Sam suggested.

“Suppose? You worked for the governor, don’t you know the protocol?”

“Not this governor, not this house.”

“I should think it would be the same with any governor,” Edward surmised.

“Then it is your invite so off you go, give a sharp confident knock but no more.”

Edward did so, giving three loud rapes upon the woodwork. He quietly waited for response but none was offered.

“Should I knock again?”

“Don’t be impatient someone will answer.” Sam assured.

“I don’t know,”

Edward lifted his hand making a fist and as it commenced its journey towards the door a woman in smart summer dress arrived within the entrance hall. “Good morning,” she greeted; her voice soft and cheerful, “Such a fine day I thought I would air the house but the dust gets into everything,” the woman approached the silent pair; eventually she asked their business. The farmer offered up Edward’s invitation.

“Oh I thought you came from Mr. Greenway, he has designs for a lighthouse to be built on South Head you know,” the woman paused without stating her position, then advanced them to a small chamber adjacent to the entrance hall, please wait in there, the Governor will see you soon.” She smiled and closed the door behind as she departed company.

“What do you think?” Edward asked of the ambience of the room.

“It is a little swank for sure and much improvement on Mr. King’s residence.”

“I feel we shouldn’t be seated or may soil the chairs.” Edward nervously admitted.

“Best be quiet and wait.”

“I’ll stand,” Edward elected and folded his arms while keeping a close eye on the closed door that was obviously the Governor’s office.

“No sit you make the room appear untidy.”

From inside an adjoining room there was the scraping of chair legs over bare floorboards, followed by a loud voice, almost shouting. Silence followed then more loud voices.

“That sounds like our Mr. Macarthur and at it again, he’s managed to depose two Governors who wouldn’t do his bidding but this time I think in Macquarie he may have met his match.” The farmer whispered as they retired to the seating.

A further silence then more raised voices and like an enraged bull Macarthur left the room slamming the door behind. Noticing the two waiting he calmed a measure but still held his fury, his face red, his eyes burning into those he met. Macarthur almost spoke, he opened his mouth, made a guttural sound and perceiving who was waiting refrained from doing so, he would never disclose his business to a convict even on who had been emancipated. Holding his fury Macarthur left the outer chamber also slamming that door on his retreat and could still be heard complaining once beyond.

“You do know it is said the man is losing his mind,” the farmer shared and with a shushing sound suggested they remain quiet and wait their turn, while trusting Macarthur’s visit had not stirred the Governor into such a state, he may renege on his promise to those who travelled with the explorers.

The wait was long; half an hour passed and still the door to office remained closed. Eventually the entrance to the antechamber from the hall opened and the woman who gave them passage entered. She smiled and without speaking continued to the Governor’s office. A short time elapsed before she returned and spoke. “The Governor will be with you shortly, she then departed back the way she came.

“Pleasant lady,” Edward envisaged somewhat louder than he had intended.

“Shush she will hear you, one doesn’t speak unless invited to do so.” The farmer warned as memories of his earlier tenure and protocol commenced to resurface.

It was still some time before the door to the office opened and an elderly gentleman in a clean but scruffy waistcoat came through. “The governor will see you now,” he quietly announced in his best cockney accent. Showing them in the official moved aside while waiting the governor’s pleasure, standing as upright as his lean frame could hold, eyes lowered to the silky oak flooring beneath his well worn shoes.

The room was small and officious, lacking any comforts of the private man, with one small bare open window through which came the distant sound of soldiers drilling and the developing heat of the afternoon.

“That will be all Williams,” Macquarie quietly spoke without lifting his eyes from his desk. Although he had come from heated debate with Macarthur, the man appeared quite calm with an air of unflappable control.

“Thank you sir,” The servant departed and both the farmer and Edward were left standing close to where they entered and somewhat perplexed to what they should do next.

The Governor gave a slight clearing of the throat and addressed his question to the farmer. “Mr. Wilcox I believe?”

“Yes sir,” the farmer answered and lowered his gaze to his gently shuffling feet.

“How many acres have you under crop now Mr. Wilcox?”

“Only seven but I am growing a good deal of produce for market.”

“Fine what we need in this colony is crops not more cattle and sheep, they can come later but food for the ever increasing population, that is our must.” Macquarie crossed the floor and took the farmer’s hand, “So this would be Edward Buckley, would it not?” he asked while still in clench with the farmer’s hand.

“Yes sir,” Edward answered out of turn, bringing a stern glance from the farmer and a smile from Macquarie.

“Would it be possible to interview Mr. Buckley alone Mr. Wilcox?”

“Yes sir,” the farmer quickly agreed as the extended hand shake broke. The farmer departed, leaving the lad nervous with his expectations somewhat unpredicted.

“Please Edward, may I call you Edward?” the lad quietly agreed, “be seated.”

Macquarie returned to his position behind the large oak desk. He was a man now in his fifties, greying hair receding and combed gently forward to disguise the fact, with piercing deep set eyes that obviously had seen much throughout his long years in military service. As a young man he served in the British army to protect Canada from attack from now Independent America and later in Jamaica before returning home on half pay to Scotland but was soon recalled and after service in Egypt and India rose to the rank of Major General.

Silently Macquarie commenced to scrutinise a set of papers on the desk before him. Once finished he placed them aside. “How did you enjoy your expedition across the mountains?” he quietly asked.

“Fine sir and never a more rugged and beautiful land could there ever be and waterfalls so high and powerful you -”

Macquarie cut the lad short with a rare smile, “Never mind the travelogue, Mr. Blaxland has already done that but what is your opinion of the land beyond?”

“Why sir it seemed to stretch forever and good grazing land at that.” Edward excitedly explained forgetting for a moment who he was addressing.

“That in itself is good news,” Macquarie once again retrieved the papers he had placed aside. “Sodomy,” he spoke without showing an inkling of surprise or abhorrence, “are you certain Mr. Buckley you were not in the navy?”

“No sir, why do you ask?”

“Never mind and Mr. Blaxland speaks highly of you, as do Mr. Wentworth and Lawson.”

“Thank you sir, they are all fine gentlemen,” Edward felt chuffed to be regarded and that in itself was a great reward.

“Fine gentlemen, as is Mr. Macarthur and others,” the Governor digressed with a slight residue of sarcasm before realising his station, “yes fine gentlemen and a task well performed.”

Macquarie set aside the lad’s papers before collecting two more documents from another pile. He continued, “I am therefore by grant from his Majesties government empowered to give you ticket of leave,” he paused and passed the document to the lad, “you do understand what that entitles Mr. Buckley?”

“I believe so sir.”

“Possibly not entirely. This grant gives you right to be your own man and travel as you will a fee man within the colony of New South Wales but does not give you right to return to England. Is that clear?”

“Yes sir,” Edward gladly received the document.

“Possibly you don’t understand the full severity of what I have spoken,”

Macquarie paused as the lad remained silent, “it means if you reoffend you will be placed back in irons and given hard labour, if you return to England then the original sentencing shall be invoked. Do you understand and agree?”

“Yes I do sir.” As Edward agreed the woman who gave him entry returned and spoke, “Mr. Greenway is here to see you regarding the plans for the lighthouse; have you yet considered them?”

“Not yet dear but I will go over them with Mr. Greenway presently, I am almost finished here.”

“Will you be taking tea with Mr. Greenway?”

“That would be nice thank you and some of that lovely maderia cake cook made yesterday.”

“What about your present gentleman?” the woman offered.

Macquarie turned to Edward, “would you like refreshments?”

“No sir,” Edward answered but would have appreciated a beer, his mouth was so dry through nerves he could hardly swallow but was most surprised that such an offer was to be made. With a gentle smile the woman left the room.

“That is Mrs. Macquarie and a finer woman there never was and now Mr. Buckley you are considered to be a free and honest man from this moment in the colony of New South Wales,” thus spoken the Governor collect a second document from his correspondence and continued, “this is for a grant of a parcel of land of no more than one thousand acres but must be selected west of the mountains as suggested by Mr. Blaxland,” passing the document to Edward he stood from his desk to show the lad out, “one last suggestion son.”

“What would that be sir?”

“Regarding your conviction, be more thoughtful where you put it in the future, or join the navy.”

Elizabeth Macquarie showed the farmer and Edward from the premises and wished them well. Once at the gate they were again met by the surly guard who glared directly into the lad’s eyes, “convict,” the man grunted, while Edward simply smiled and passed but not before waving his ticket of leave in front of the man’s face.

“No convict sir but a freeman,” Edward provoked.

“That doesn’t change anything, the stain remains and like a glob of tobacco spit between the eyes, it’s still there,” the guard sneered while allowing passage and once they had passed spat violently onto the ground.

“Let it be Edward keep moving,” the farmer advised taking the lad’s arm encouraged him on, “you wouldn’t wish to lose what has been granted within minutes of receiving it.”

“I’m not concerned, not with the likes of him.”

“So what now?” the farmer sighed in happy relief as they walked towards town, dodging arrogant convicts and children at play, “how do you feel – how does it feel to be a free man?”

“In some ways cheated,” Edward answered as he passed his papers to the farmer for keeping, “best you take charge of those as I’ll only misplace or soil them.

“Cheated, in what way?”

“Here I stand a freeman without freedom to return home, I don’t call that freedom.”

“Be patient lad, give it time, firstly let us get you some new clothing and release you from that stain the guard accused; come on lad I know just the place to get your new threads.”

Not too distant from the main harbour and Circular Quay, was an area known as the Rocks where a market could be found from sunup to sundown on each day except for Sunday, selling almost everything available elsewhere in the Empire but at unrealistic Sydney Town prices, which could fluctuate up or down at any given time during the single day, to take advantage of passing trade.

The Rocks was also a place to find inexpensive housing, with row upon row of small terrace houses, all co-joined with dividing walls so thin, every argument and conversation could be shared with their neighbours and back yards so minute it was unlikely enough greens could be grown to feed a sparrow, or so shaded by construction only minutes of the midday sun reached the ground, while the place for night waste was naught but a narrow lane to the rear, which eventually, when it rained, was washed to the sea and the port.

For folk born to poverty they were a virtual palace and proudly did they decorated their doors and window frames in varying colours from deep blue to red and green. Often using more than one colour on the same door or window frame, never considering the old precept of blue and green should never be seen. Otherwise the dwellings remained as drab as a London Smog, while most entertainment was conducted in the bijou of their front courtyard, with its single tree or shrub and border of seasonal flowers, or with the procession of simple folk on their way to market.

The farmer soon guided Edward to the cheap clothing stalls, where in no time he had been fitted out like the free man about town he had become, even taking on the appearance of Currency with his worker’s suntan and developing colonial attitude towards his superiors.

“So now that you have truly changed from convict to emancipist what is it like to be that freed man?” the farmer again asked as they slowly strolled through the streets towards their tavern.

“With gratitude Sam, yet you have always treated me so.”

“What are your future intentions?”

“The Governor has granted me a thousand acres but it has to be selected west over the mountains and not around the settled areas. In some ways I expect it is done with intent.”

“What is your meaning?” the farmer asked.

“According to what Mr. Blaxland proclaimed, it is a grant given with the knowledge it will not be taken as there is a caveat on settling there.”

“True for the present but I believe it is given more for a time when order can be established in the wilderness.”

“Mr. Blaxland also suggested so,” Edward agreed.

“Will you take up this grant?”

“Possibly some day but in truth I’m not yet experienced to run my own property,”” Edward paused and with a measure of modesty continued, “If you will have me, I would like to remain with you at Parramatta.”

“I cannot pay you a freed man’s wages but you are more than welcome to stay and share my meagre pittance for as long as you wish.”

“Even less would suffice Sam, I have never been paid a wage and at home there wasn’t money to pay such a large family, only our keep and the occasional treat at birthdays and Christmas.”

On reaching the tavern Sam allowed the newly freed citizen first step through the door with a bow and a smile, “what I could offer is partnership,” Sam suggested and followed into the dimly lit, smoke filled tavern.

“For now what I have is enough but I will let you shout me a beer.

“Good idea, come on.”

The beer became a number with a visit to their table from Maisie, the tavern’s publican, enquiring of Sam why his servant had discarded the mustard stripes of a convicted man. The farmer explained and enquired of her new help, a young girl who appeared to be making merry cheek with a group of merchant marines. With a slap to her rear and a squeal the girl departed their company and on passing Maisie questioned their conversation.

“But the usual Mrs. Bradshaw but Lizzie is a good girl.”

“Yes Lizzie you are all good girls, now do some work and get these fine gentlemen their drinks.” Maisie departed to have words with a rowdy drinker who was about to throw his weight in anger. A word from the publican and he settled.

Lizzie returned with the drinks, “are you from the ships,” she asked, as there were a number of free settlers arriving with coin in their pockets and hope in their hearts to develop their fortune.

“No Lizzie we are from near Parramatta.”

“Parramatta, isn’t that on the way to the mountains?”

“It is on the way but well short.”

“Did you know Mr. Blaxland has only last month crossed the mountains? I read it in the Sydney Gazette,” the girl shared, being more proud of her limited reading skills than news of the crossing.

“Hey girl where’s our drinks!” A voice interrupted from across the room. She ignored the call, a second demand brought her to turn and give some rude suggestion with her hand as she had become more interested in the young man from Parramatta than the ruffians from the sea.

“Yes that we know and Edward here was with Mr. Blaxland during the crossing,” the farmer proudly related his friend achievement, sending Edward to blush.

“All those savages and cannibals,” the girl quivered, “and I believe there are other countries there and a large inland sea and -” the girl cut short, she had heard so many untruths about what was to be found across those mountains she could not retain them all, or explain them in a single sentence.

“None of that Lizzie, only more land but you should ask young Edward here he’s seen beyond the mountains.”

Again the lad blushed, “there is only land and lots of it, stretching ever westward but I assure you no settlements and no cannibals.”

“What of China?”

“No Lizzie, no China, no towns, only vacant land waiting settlement.”

“What about the savages?” the thought sent a quiver through the girl, she had heard of cannibals from those who made trade with the Pacific islands, even how Lieutenant James Cook, the then captain of the Resolution had been eaten in Hawaii on his final voyage.

“I would say plenty of natives but they aren’t cannibals, they are much the same as you see around Sydney Town.” Edward admitted. Once more a voice demanded service but still Lizzie held her conversation.

“I think you should see what they want or you will have Maisie after you,” Edward warned as he was growing tired of the girl’s fantasies.

“Are you from England Lizzie?” the farmer enquired, noticing her lack of accent.

“No sir I was born here in Sydney Town but my parents were from some town called London I think.”

“Would you like to go to England?” the farmer asked.

“Heavens no sir, that country is full of thieves,”

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,221 views