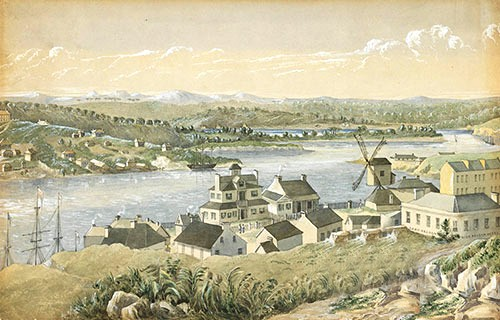

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 12 Aug 2019

William’s intention was a few days but soon settled into his brother’s company and that of the others. Often he would sit through the darker hours talking with one or the other, Sam being his favourite as he gleaned knowledge for his need when he set up his own property.

Bahloo soon found interest in the newcomer and William would often walk the countryside with the lad, who by all accounts was now an adult, explaining his ways and the names of this and that and how Bahloo would laugh as William, unlike his brother, stumbled over native language, or soon forgot what had to be told. William blamed his age, declaring it much easier to learn as a child, as now his mind was set and his tongue tied to English.

A short while after Williams arrival there was a visit from the police who had been chasing the renegade convicts, discovering them encamped some thirty miles to the west beside the actual Macquarie River, near where Fish River entered. The four were taken with such surprise they didn’t have time to aim their weapons and without injury to any of the police, all were brought down in the first volley and buried where they fell.

One, a lad of unknown name lived long enough to ask if the locket held by the man with the scar could be returned to Elsie and to tell Edward, he would never have done what Jock had suggested. The policeman relayed the dying lad’s cryptic message and Edward accepted it without further explanation but there was a choke in his voice as he remembered Malcolm and his innocence and how he became influenced by such an evil man.

Elsie was now showing signs of carrying child and Hamish was beside himself, displaying his pride as often as possible and dogmatic on the child’s name, his father was Hamish, he was Hamish so would be the child, bearing a Scottish name but never a Scot. It was then Elsie corrected her husband – “but Hamish my grandparents on my mother’s side were from Glasgow, that will make the child partly so.” Hamish there after held his peace on the flow of Scottish blood.

“What if it is a girl?” Sam asked as they held their monthly meeting beside the river’s cooling water. Elsie had arranged her usual hamper and spread blankets in Coolabah shade.

“I never thought of it being so,” Hamish admitted with the arrogance of a father to be.

“So what if it’s a girl,” Edward resounded Sam’s words.

“It will be Elsie’s choice,” Hamish magnanimously declared. They all turned to Elsie.

“If it is a girl it will be Elizabeth, after my mother.” Elsie quickly declared before Hamish could have second thought and supply a name of his own.

“I thought you mother was Rose,” Hamish appeared confused.

“Yes Rose but it is Elizabeth Rose and she preferred her middle name.

“Elizabeth, yes a nice name,” Sam agreed.

“That’s a Devon thing,” Edward admitted.

“True, I am George William Buckley but known as William.” William declared.

“And I am Lewis Edward but always Edward and our da also that way known.” Edward turned to Sam.

“Sorry to disappoint you, just Samuel no middle name.”

Edward then turned to Hamish.

“Just Hamish, we were a poor family,” he laughed.

“What about you Piers, sitting there very quiet as if you are hoping we would pass you by,” Sam asked.

“That I was,”

“So out with it,”

“You won’t tell anyone or laugh?” Piers blushed crimson.

“Like who?” Hamish asked.

“It’s Trafalgar, Piers Trafalgar Bradley. Now you know.”

“How in hell’s bells did you get the name Trafalgar?” Hamish’s voice lifted towards mirth but on seeing the lad’s embarrassment lowered towards interest.

“My grandfather was killed on the Victory with Lord Nelson in some sea battle.” Hamish commenced to laugh. The others followed.

“I told you not to laugh,” Piers became quite hurt.

“No Piers it’s a fine name, we are surprised that is all,” Sam apologised as the attention was once again on Elsie.

“I guess she would be Elizabeth Rose as I also lack a middle name.” Elsie admitted.

“Why not Elizabeth Rose Elsie,” Hamish suggested.

“A little ahead of time there Hamish, besides I have the feeling it will be a boy,” Elsie recommended.

For a time the conversation died then Hamish put across that there was a break in the south paddock fence and sheep were on the road.

“Fixed,” Piers corrected, “Sam and I fixed the fence yesterday.”

“Good,” Edward appreciated, “but can you fix the weather.”

“Bahloo said there is rain on the way,” Sam offered.

“When it comes to nature what doesn’t Bahloo know,” William shook his head with the thought.

“I suppose they have been here for thousands of years and there isn’t much else but weather to talk about.” Edward stood and walked to the river bank, “the river’s down.”

“So are the two waterholes.” Hamish added.

“When is Bahloo’s rain coming?”

“You know the blacks soon could be six months.”

“Better not be.” Edward returned to the group, William what are you going to do with your land?”

“Like you, sheep I guess but not so grand.”

“If it is right by the others, we can give you a number to start your flock.”

The western horizon had a long brown beige wall of unknown substance stretching fully from north to south and had been visible since early morning. The late summer days were hot without the slightest cooling breeze, while the nights hung still and uncomfortable.

“What can that be,” Hamish asked, removing his hat and wiping the sweat from his forehead before it had the opportunity to run and tickle along his nose, “can’t be another flaming volcano.”

“Dunno’ haven’t seen it before,” Edward answered as Bahloo arrived from fishing.

“Catch anything?” Edward called. Bahloo held aloft a stick with three fish attached, “what kind are they?”

Bahloo answered Edward’s question in language.

“What did he say?” Hamish asked.

“He said fish. Obviously the word covers all types.”

“Hey Bahloo what is that out on the western horizon?” Hamish asked and again Bahloo answered in language. “What did he say?” Hamish impatiently demanded.

“He said big wind but couldn’t place it in English, “he said dirt wind.”

“Cyclone?” Hamish questioned, “I thought they came out of the sea?”

Early afternoon and the horizon’s brown smudge appeared much closer but still no wind. On the occasion one or another would look towards the smudge in wonder and hope it wasn’t Hamish’s predicted cyclone. Edward concerned for the stock and if the wind was strong the chickens would be somewhat exposed. Elsie thought it wise to bring in the washing although not yet dry, while Sam with Piers paced the yard to be sure there wasn’t anything that could become airborne and cause damage.

As the afternoon sun lowered into the west it shone through the haze, giving a sepia tone to the atmosphere, taking away the blue of the sky and the green of the trees, dissolving into the brown grass that stood straight and still. Hamish looked out across the field and spoke a single word, “Bushfire.”

“It doesn’t appear to be smoke,” Edward contradicted.

“No but the grass is so dry, we should burn off.”

“Good suggestion but first this dirty wind of Bahloo’s,”

“I don’t think it is wind,” as Hamish spoke the first of the haze reached the top paddock. It was dust and as thick as soup while moving slowly across the fields in a wall reaching high into the cloudless vault. “I should go and see if Elsie is alright.”

“It’s a flaming dust storm,” Edward cursed and ran to close windows as the late afternoon turned into a sepia night and sent all choking indoors, even so the dust followed, seeping through every crack and gap.

“Where’s Bahloo?” Edward panicked as the cold front from the south west picked up strength sending even more dust in scatter.

“He’s over with Elsie,” Sam answered while placing bedding at the bottom of doors.

With the first of the dark, the wind increased with gusts that rattled the windows and made the new sheet iron roofing, brought at great expense from America, to screech and timbers to creak, resembling the growling of a ship’s hull against a heavy swell. With each gust and creak eyes were drawn upwards bringing Piers to question their building skills but Edward assured both houses were sound, with Hamish’s overseeing of their structure and his fastidiousness, they could be nothing else.

Morning came with an eerie stillness while everything was covered in red dust, with drifts a foot deep along the side of the houses and completely covering the vegetable garden. Quickly James went to the chicken coupe and to dismay found them all dead, choked by the dust and partially covered. Returning he related his find. “What about the sheep?”

Both Edward with Hamish disquietly progressed to the first paddock and were relieved to find to an animal they had headed into the thick scrub along the river bank and were fine. During the day they rode out to inspect other paddocks, determining sheep had more sense than credited and not one single animal appeared to have circum to the choking dust.

A number of the dead chickens being freshly demised were soon plucked and readied for the pot, others had their meat salt cured and hung but that was the end of fresh eggs for the while, although when cooked it was said they did have a gritty texture. It was suggested with the restocking of the pen, a better shelter should be created as it faced the west and the full force of any weather that often came from that direction.

That was the week Bahloo went walkabout and had not returned by the month’s end. Usually he would only be gone a matter of days, once a week but never longer and there was much concern for his wellbeing. During the first days of the following month a lone native was seen crossing the top paddock towards the river. Edward quickly approached from his work on the new vegetable garden and spoke using language but conversation was limited because of dialect.

Edward did manage to have the man understand he was enquiring about Bahloo but the native shrugged his shoulders, saying he didn’t know Bahloo, he then moved on without speaking further.

“No luck eh?” James suggested coming up from behind Edward.

“Luck?”

“I did hear you using Bahloo’s name, did he know of him?”

“He said he didn’t know him and was somewhat rude about it.”

“Don’t worry; I’m sure Bahloo knows what he’s doing.”

“Where’s William?”

“Down at the sheds Hamish is teaching him and Piers how to shear a sheep.”

“Knowing Piers disinterest in sheep that could be fun,” Edward nodded towards the bottom water hole, “almost empty, had a ewe stuck in the mud yesterday, she was so waterlogged I had to use the horse to drag her out.”

“Does the dry weather usually last this long?” James asked being somewhat new to the country and its changeable weather.

“I’m told it can last for months, even years.”

“I guess you are fortunate to back onto the River.”

“Yes but even that is low and now I see smoke about and all we need with the grass so dry is bushfire.”

Hamish arrived from giving his shearing lesions, “what’s the topic?” he asked.

“The dry, bushfires and you teaching Piers how to shear.”

“Tried, would be more accurate but he isn’t concentrating, more interested in the daughter of the tavern keeper across the river.”

“He’s a little young for that?” Edward suggested.

“Almost seventeen now, I guess his nuts are swelling,” Hamish crudely laughed, “and by his conversation he isn’t one of your lot.”

“That has been more than obvious from the start.”

“By the way, Sam is feeling poorly again, his lethargy is back and his bones ache, Elsie is smothering him with sympathy,” Hamish related.

“Swamp fever,” Edward surmised.

“I guess that will do for a title,”

“I’m worried about Sam,” Edward empathised.

“Yes we both own him much.”

“I will call on him in a little while.”

“You mentioned bushfire, have you had word?” Hamish asked.

“No only smoke here and there.”

“Possibly we should start burning firebreaks around the property now that the weather’s calm and rain is on the way.” Hamish suggested.

“Wise move Hamish and soon.”

The following few days were too windy to set the firebreak but the continuing dry did have a reverse of folk leaving to the south, wagons piled high with belongings and desperate faces that had obviously seen hard times and had not bargained for drought. Many taking up their selection in a good season while overstocking in belief they had found god’s country, which it could be once one learned to roll with the weather.

“Do you think we will come to that?” Hamish solemnly asked while he and Edward stood by the fence line and gave sympathetic courtesy to those who passed, often supplying food to help along their way.

“I shouldn’t think so, the dry can’t last much longer and as Bahloo said it would rain soon.”

“Yea but the rain as well as Bahloo are both conspicuous by their absence.”

“True I hope he is alright I would go search for him but he never gave directions or mentioned his travelling when he last returned.”

“Don’t fret Edward, he’ll be jake.”

“Another one of your colonial expressions Hamish?”

“I heard the coach driver use it.”

“I also concern for William, he remains interested in taking up land on the Bathurst Plains.”

“Edward you can’t be everyone’s keeper,”

Week’s end and still no rain. The previous day did show promise with black clouds gathering to the north east. “Rain,” Hamish said with hope, his eyes cast eastward to the mountains.

“The wrong direction for this time of the year but I guess Sydney is getting its share.”

“Then it’s back to the bucket brigade for the vegies,” Hamish said remembering how they had to do so while living with Sam, “come on grab a couple of buckets and best we start.”

On reaching the river they notice a native canoe. “Visitors,” Hamish supposed, noticing a single black man slowly paddling in their direction.

“It looks like,”

“It is Bahloo,”

Bahloo slowly paddled towards where they waited and by his action appeared to be carrying a wound, while his body was somewhat emaciated. As he reached the bank the last of his energy was spent and he collapsed into the canoe. Quickly and with little effort he was carried up to the house. Elsie met them on the step.

“Is that Bahloo?” she asked hardly recognising his thin arms and legs that appeared to dangle about without control.

“It is and hurt, as well as almost starved,” Edward admitted.

“Bring him onto the verandah and let me have a look at him.” Elsie said while preparing a bed of sorts out of a pile of hessian bags used for bailing wool clip.

“It looks like a spear wound,” Edward presumed.

“It doesn’t look too deep and he’s put some gunk on it, I’ll clean it away and disinfect it.” Elsie went for a bottle she kept for such a purpose.”

“What is it?” Edward asked.

“Tea tree oil, dad learned it from an old bushy who learned it from the blacks.”

“Does it work?” Edward asked showing a measure of doubt.

“It does ask Hamish, when he had that infected wound from the sheers.”

“It doesn’t smell very nice,” Edward turned his nose away as Elsie applied it to the wound.

“Has to smell like crap to work,” Hamish said.

Obviously the tea tree oil had some useful properties, as with a good feed, a day’s rest Bahloo was back to his usual cheeky persona but wouldn’t divulge how he received the wound.

“Have you been chasing the Sistergirl’s out west Bahloo?” Edward asked believing a little levity would bring Bahloo to recall his travelling.

“No Sistergirl, Bahloo no chase Sistergirl.”

“How did you get the wound?”

“No chase Sistergirl.” Bahloo enforced displaying a rare measure of annoyance; as quickly it subsided.

“Alright then Bahloo, but you should rest up for a while before you go off again.”

“Bahloo ready to work for Edwa,”

“Don’t you think we worry about you going off like that without saying?” Edward scalded but all he received for his concern was a cheeky grin, “you will let us know where you’re going in future,” Edward demanded and a promise was given but it was obvious one the lad would not keep.

“Anyway Bahloo where is this rain you promised?” Hamish asked.

“Up along what Gubba call Quarrie River, plenty rain.” Bahloo let slip.

“Ah so that is where you’ve been, out west.”

“Maybe Bahloo go west, maybe he didn’t, maybe Bahloo only heard about the rain.”

“Maybe Bahloo tell bullshit eh?” Hamish supposed.

The first calm day was firebreak day and nervously all advanced to where they thought it best placed. It was Bahloo who had the best notion what to do, as his mob had been burning off country for millennia.

“Ya’ burn a bit then bash it out,” was his suggestion as he commenced to make fire in his traditional way, ignoring Hamish and his flint and tinder box.

“Some Frenchy Frog has invented a better fire lighter,” Sam commented from the sideline as both Hamish and Bahloo raced to produce the first flame. Hamish won with ease but most attention was given to Bahloo’s method.

“Have you a supply of these new firelighters?” Piers asked.

“No I only read about them, I’ve never actually seen any. They are called allumettes,” Sam explained.

“What’s that in English?” Piers demanded.

“I couldn’t say possibly there isn’t an English word for them yet.”

Eventually Bahloo’s attempt burst into flame and Hamish extinguished his own to give Bahloo his due.

Elsie came down in the early noon with a hamper for their lunch, finding a substantial width of burnt grass and a measure of satisfaction with their work. Would it prevent fire spreading? That was a good question and none could be sure, even Bahloo could not say as his reason for burning country was to encourage new growth with the rain and flush out little animals for food and not to protect other parts, although native burning did protect even if not their intention.

That afternoon clouds were forming on the northern horizon, bringing many fingers to point and hope.

“That no rain,” Bahloo assured and pointed to the south east, that way for rain.”

“I told you,” Edward agreed.

“When?” Hamish growled.

“Maybe to morrow maybe many days.” Bahloo answered.

“Many Bahloo?”

“It will rain.”

“Maybe Bahloo should do a rain dance.” Hamish grumbled.

“Bahloo no dance, it will rain. Dance for rain that silly.”

“Don’t black men dance for rain?” Hamish was leading his black friend, who simply walked away complaining about Hamish’s silly suggestion.

Washing day, firstly water was drawn from the river and a large copper container filled above a well stoked fire. Hamish had purchased what was called a washing copper from a traveller and installed it in the back yard well away from the house.

At its first usage all gathered around with keen interest, taking turns to prod the bubbling soup of clothing and soap with the washing dolly, now it was left to Elsie to swelter in the day’s heat her face even more ruddy from the fire and steam.

“Women’s work,” was the general consensus and to help Elsie with such work a mangle was purchased to extract most of the water from the finished washing.

“What if I wasn’t here?” Elsie’s protested as they gathered around watching the procedure as a pair of Hamish’s long-johns went through the large wooden rollers of the mangle to become as flat as a slice of bread and ready for the line.

“Piers, he is the youngest;” but Piers soon suggested otherwise, declaring if it were left to him they could wear their clothes until they rotted and fell from their bodies.

The clothes line was a thin rope strung between a tree and the house and propped at centre with a long pole. Sam had made the pegs and fine they were. While pegging out a selection of shirts and badly stained long -johns, finding it almost impossible to remove the crotch stains from Piers underwear, something caught Elsie’s eye. It was to the North West and at first glance she believed it to be clouds, a second glance brought concern, it was smoke and appeared to be beyond the river. “Fire!” she cried and hurried to the field, pointing towards the smoke.

“It’s across the river,” Sam suggested.

“Bert Hannaford’s place is about there,” Hamish inferred as Edward and James came from gathering wood for the kitchen.

“Should we go over and lend a hand,” James offered.

“Wouldn’t be much use, by the time we arrived the fire would have moved on and it’s travelling with the wind towards the town.” Hamish observed.

“Come on they may need us in town.” Edward hurried the others to depart at haste. Bridge Town wasn’t what one would imagine as a town to be. Consisting of a dozen or so dwellings, the tavern where Piers spent much of his spare time chatting with Sarah the innkeeper’s daughter, a coaching station with stables and a store that stocked hardly anything useable.

As the cart loaded with everyone except Elsie and Bahloo crossed over the bridge the fire came from the west and caught the forest of eucalyptus trees west of the road. Soon it was roaring through the high canopy at an alarming speed, being fed by the tree’s oil and increasing in heat and villosity as the wind drove it on.

Beside the small eucalyptus forest was a stretch of pasture, now dry and beckoning for burning and stretching towards the river. With the radiated heat from the eucalyptus oil and flying embers the long grass exploded, scattering startled sheep to panic, some with their wool smouldering, causing the fire to spread as they ran in fright.”

“We should do something?” James cried as the flames leapt from forest canopy ahead by half a mile to the grass towards the town.

“Can’t help the sheep but we can the town.” Hamish turned towards the east and town, while the fire rushed up a slight incline and down at greater speed.

On reaching town they found the entire population out, men, women and children all waiting with fear on their brow as the fire edge closer by the minute. If there wasn’t any change of wind direction, the first to meet the flames would be a number of adobe and canvas temporary dwellings on the outskirts of the town, situated under a stand of trees for shading. The owners cleared out their belongings to safer ground and stood close by in hope they could stamp out flames with length of leafy branches.

Within feet of the simple structures the fire intensified, leaping up into the canopy above and raining cinders down on the canvas roofing of the temporary dwellings, within seconds they erupted into flame, there was nothing that could be done except stand back and wait. Moments later it commenced its rush towards the first house with all ready with their branches and the occasional bucket of water, useless as the heat evaporated the water before it reached the seat of the fire.

The first house went with a loud whoosh and then the wind changed, sending the fire back on itself and down the slope towards the river.

“It’s heading for the narrows; it could easily jump the river there.” Hamish hollowed over the crackle and roar of flames in the burning tree tops.

The town was saved but the boys knew if it crossed the creek at the narrowing it was only a short distance up the slope to their firebreak and the fist paddock and their flock.

“Is Ben Hannaford here?” Edward shouted above the noise.

“I’ve over here,” the man answered from close to the destruction that was once a house.

“Has you property suffered?”

“If total is suffering, than yes,” yet the man came to the rescue of others while knowing he had become destitute.

“Once you have settled come and visit, with some luck we can help you restock.”

“Appreciated,”

Quickly they started back and on crossing the bridge the wind carried the fire over the narrowest part of the river and in a flash caught the grass on the south bank. In the distance they saw Elsie and Bahloo beating out the spot fires started by cinders carried on the strengthening breeze. What the failed to notice was the sky above, now black and promising.

As the front met the firebreak it stopped and headed along its length in a southerly direction following the paddock and missing the fence.

“It’s raining!” Edward cried loudly as the first heavy droplets splashed to the parched earth sending up miniature clouds of dust. Then the heavens opened.

“It’s a bloody miracle!” Edward shouted and commenced to whoop and dance around within the downpour.

Arriving home and soaked they all rejoiced, not only did the back burning work but at last the rain had come. Bahloo came up with Elsie, her with sooted face, he with scorched parts to his frizzy black hair. Bahloo quickly approached Hamish, “I said it would rain,” he spoke in language knowing it would irritate Hamish to do so.

“What did the cheeky bugger say?”

“He said he told you it would rain.” Edward translated.

“Crikey Bahloo, it would have to rain eventually but you didn’t say when.”

The rain continued through the night, the following day and for two days after, swelling the river to such an extent they no longer had to save their flock from fire but now it was flood and as had occurred with Sam on the Branch Creek at Parramatta, they lost their vegetable garden, plants, soil and fencing all gone with the torrent on its way west to the Macquarie River. Now Hamish had another question for Bahloo, “when will it stop raining?”

Bahloo laughed and shook his head, “soon,”

On the third day the sun came out and its warmth gave a feeling of wellbeing even if the river was now only metres from the first house yard but like all rivers eventually the level dropped and praise was given to their decision to build high.

By week’s end Fish River returned to its natural banks and life for most returned to a kind of weird normality, others loosing too much to start again, simply packed their few belongings and moved on to find that greener pasture.

With the better weather there was another improvement within the colony, being the further development of a banking system and the naming of the Bank of New South Wales with an agency in Bridge Town, now when there was gold to be delivered to their agent in Sydney, it could be sent by mail and payment deposited.

There was still gold to be found in the washout and occasionally, when the mood suited one or the other would fossick about, finding small nuggets and in pockets granules, placing it aside until there was enough to send to their Sydney agent, who after consideration would deposit its value in the estate account.

It was a strange arrangement but worked, neither George Roberts nor the fossickers became greedy, realising it would be their loss if word would out and Edward’s promise to Macquarie held firm. As for William, no one had told him about the find but after he had been at the farm for sometime and still undecided what he should do about moving on, it became obvious to both Hamish and Edward an offer could be made.

It was during their monthly meeting picnic by the river with Elsie’s hamper placed under the shade of Coolabah on grass mown short by grazing sheep, that Hamish brought forth an idea. Firstly he spoke to Sam, again being well enough to do light work about the house and garden, yet not over his blight which could come from a perfect day leading into a miserable night.

“Sam, Edward and I were thinking we should be offering you a full partnership in the Estate.” The proffer came from Hamish during the passing around of chicken sandwiches and Elsie’s fresh lemonade and home brewed beer. Sam gave a light smile but didn’t immediately answer.

“Yes you have been good to us and we would not have a partnership to offer if it wasn’t for you,” Edward gladly placed with Hamish’s suggestion.

“Most kind of you but I must decline.”

“Why?” Hamish insisted.

“Yes why?” Edward replicated.

“I’m past all that, I would rather watch the two of you scheming about what to do next, it’s better than a novel and now Piers has found his niche it leaves me free to do so.”

“Yes he would never make a farmer, best he become an innkeeper and chase his little filly. It is your choice but you will always be part of our little family,” Edward insisted and turned to William, “are you still interested in heading out on your own?”

That notion much concerned William, finding this new country irreparably alien to what he knew to be farming, with its broad skies, spasmodic rainfall and changeable weather, bringing him to realise he knew little and on his own would more than likely fail.

“I would love to do so but I am not yet ready and possibly never will be,” he honestly gave answer.

“Hamish and I have had thought we could also offer you a partnership.”

“Most kind brother but is there enough profit in the wool clip to take on another.”

“That is growing yearly and back in England the demand is increasing to such a degree there can never be enough grown in New South Wales, besides there is more than wool attached to the offer,” Edward answered while throwing a quick glance towards Hamish for support.

“Yes it comes with a promise of silence.” Hamish attached.

“I don’t understand,”

“You must have realise we all live a little better than most of our contemporaries?”

“I guess it may have crossed my mind.”

“We have a little gold mining concern.” Edward explained their situation, his promise to Macquarie, their fear of creating a rush and the need for concealment.

“What of you Sam and Elsie, what would think of me joining your little,” William smiled, “family and what of you James, what do you think?”

“William you are already family.” Elsie agreed. The others likewise agreed.

“Then I would love to,” William answered while appearing uncertain with his agreement.

“Good, we will have the papers drawn up,” Hamish proposed.

“Word would be more that enough.”

“No William, it must be legal, there are too many twists in law in this country to trust otherwise,” Edward insisted.

“What of this gold you speak of?”

“We found it down in the washout by the Pepper Corn tree, well the tree that was there until uprooted during the flood and have been selling it on through an agent in Sydney for some time,” Edward explained.

“What is the need for secrecy?” James asked.

“Simply the colony isn’t ready for gold mania; it would mean ships arriving from every corner of the world, with sailors jumping ship, folk leaving their work in the towns and worst of all convicts out of control.” With his and Hamish’s convict past and present restriction on travel quickly brought him to chuckle as he waited his brother’s final confirmation.

“But if there is gold in your creek, there must be more elsewhere?” James added to Edward’s worrying list.

“True but one can only hope that by the time it is found the colony will be in a better state to cope with it.

“Then I would love to join with you all.” William reiterated.

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,207 views