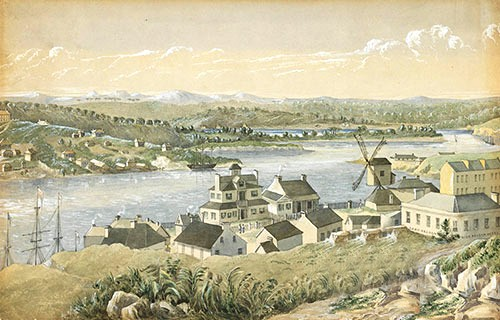

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 29 Jul 2019

Departure day found Bahloo sleeping at the door curled like a puppy in a basket, with only a covering of kangaroo hide to keep away the elements. Edward all but tripped over the lad while going to the long drop for his morning ablutions.

“Why don’t you sleep inside the house, or in the hut we built for you?” Edward asked on his way back but a lifetime of open spaces could not persuade the lad to become that domesticated, no more than he would use the outhouse to dispose of bodily waste but Edward did manage to have him travel further into the scrub than close to the house paddock fence line.

James prepared breakfast and served Bahloo a portion at the door, the lad quickly consumed his meal and hurried to the horse yard. “You have to give it to him – he’s keen,” James admitted while collecting Bahloo’s empty plate from the step.

“Suppose I should be going.” Edward collected his hat and saddlebags.

“Have you got everything?”

“Yes I think so, I have some of the gold; I’ll show it to Mr. Macquarie and ask for his opinion.”

“Good Morning,” Hamish called as he cross the yard carrying an old pair of canvas trousers which he passed to Bahloo, “try these on for size they’ll fit where they touch.” Without hesitation or a miniscule showing of modesty the lad withdrew his platted grass lap-lap and drew on the trousers. “They are on backwards,” Hamish shook his head in mirth as Bahloo removed the trousers and reversed their wearing. “That’s better; you now look like a Gubba.”

“Righto I guess I’ll be going,” Edward turned to James, “are you sure you don’t wish to come?”

“I’ve had enough of civilization for a while.”

Edward turned to Bahloo who had already climbed onto his mount but couldn’t work out how to stirrup his bare feet. “No bare feet Bahloo, if they slip through the stirrup irons and you come off it will be the end of you.”

“Hang on,” Hamish called from half way back to the house. A short time later he returned with an old pair of boots, “put these on.”

The lad may have yielded to the trousers but wasn’t in the best of design about the boots. With persuasion he relented, “how about a shirt?” James offered but the lad had come to the terminus of what he would wear.

“Righto, we’re away,” Edward loudly sounded and led out of the yard with the black lad behind happy and laughing and lacking the slightest design of fear or style. Yet he remained aloft and was still balanced like a black head on a carbuncle as the two reached the road.

“You alright back there?” Edward called as they commenced their journey.

“Bahloo alright, Bahloo ride good.”

“Yes you ride good Bahloo but no silly stuff – alright?”

“No silly stuff Edwa,”

On progressing towards the uplands they met with much traffic travelling west, mostly small groups with their sheep but now business was developing, travelling salesmen of all persuasions, peddling their wares to the small landholders.

With the salesmen came those prepared to set up business in the developing communities now sprouting like mushrooms after the spring rain, while offering support for the newly named squattocracy, a title coined to describe those who illegally took up land. Passing to the west were carpenters, cooks, wheelwrights and a host of others, even to Edward’s surprise he chanced upon a man selling books.

“Do you know books?” Edward asked of his black friend once the merchant had passed.

“What are books?” Bahloo asked.

“They contain words and you read them.”

“Read?”

“Yes you read the words with your eyes like you hear the words with your ears.” Now Edward was in completely new territory and Bahloo appeared more confused than ever.

“It’s like your songlines Bahloo but instead of being in you head they are in books, you make pictures on rocks and you read them, well we make –, Edward paused, “never mind I’ll show you when we return home.”

“These books talk to Edwa?” Bahloo continued his tone more confused than before.

“It’s too difficult to explain Bahloo.”

Not long after meeting the travelling bookseller, two men of dubious conviction came by giving more than a second glance as they approached.

“You can smell a sheep shagger from a hundred yards.” One turned in his saddle and called back as they passed. The other laughed and made a remark about Bahloo being Edward’s comfort for the night and with loud voice placed a further insult, “what do you call a savage with a horse?” was comically asked of his companion.

“Dunno’,” his mate answered in equal strength.

“A horse duffer,” soon they were out of hearing and only their laughter carried back.

“What is horse duffer?” Bahloo asked.

“Someone who steals horses,”

“Oh,” It was most obvious the lad remained thinking. Eventually he continued, “Edwa what is a sheep shagger?”

“It is a man who fucks sheep,” Edward honestly answered with more than a measure of muse, while considering how the lad would envisage such an expression.

“Oh,” again it was clear the lad’s mind was active, “do Gubba fuck sheep,” he asked in language not knowing how to express his question in English.

“No Bahloo they do not, the man was being insulting.”

“I don’t think I would like fucking sheep.” Bahloo shook his head and pointed ahead to a small flock of sheep being driven along the road, “plenty sheep there for Gubba to fuck.”

“Where are you headed?” Edward called to the closest mounted drover who came to meet him.

“Some ways past the Macquarie River, I hear there is plenty of good land there.”

“True, I’m this side but you may run into cattlemen across the river and they don’t like sheep farmers.”

“Thank you for the warning. Did you have trouble with them?”

“Only verbal but they did kill most of the natives in a local camp under the pretext they had been attacked by them.”

“Are the local blacks hostile?” The drover asked while his eyes rested cautiously on Bahloo.

“Wouldn’t you be if half your lot were killed?”

The drover removed a pouch of tobacco from his waistcoat pocket and commenced to fill his pipe. “Don’t know about that but best be aware, there are a couple of bolters back along the Katoomba stretch and they are bushranging, the bailed up the mailman last week and stole his horse, left him to walk back in his underwear.”

“Warning appreciated; best we were on our way.”

“I don’t think Gubba like Bahloo riding a horse,” Bahloo observed.

“Some Gubba’s don’t like blacks doing anything best to ignore them.”

Late afternoon and it was decided to rest the horses with the climb into the west of the Blue Mountains but a short distance ahead. As Edward was setting up camp Bahloo, after removing Hamish’s heavy boots, disappeared into the scrub returning some time later with a small wallaby he had brought down with his boomerang. “Got tucker for Edwa,” he proudly announced holding the lifeless animal above his head.

“Good fella’ it was going to be salted mutton but you cook it, I wouldn’t know how to do so without preparation.”

“I show Edwa how to cook blackfella’ style,” pulling apart Edward’s camp fire the lad dug deep beneath the coals, then after singing the fur from the haunch and tail part of the animal he buried it beneath the coals and covered it.

“It is as easy as that eh Bahloo?” Edward amazed.

The lad laughed loudly as he built the coals back over the meat, while chanting some ancient songline.

As the sun sank into the western plains and the sky began to sparkle, Bahloo served his meal. Edward was most impressed at the simpleness of the lad’s cooking and told him so.

Before bedding down Bahloo commenced to sing. “What are you singing Bahloo?” Edward asked.

“It is the old way to travel from the big water to the flat lands out there.” Bahloo pointed back towards the west. “What I sing was how to get from what you call Quarrie River to Katoomba.”

“It is the Macquarie River and Mr. Macquarie is our governor and now also yours.”

“Mr. Quarrie he is Gubba not black fella’.”

“Yes I suppose you are correct but I’m afraid month by month, year by year more Gubba come and soon there will be so many, there will not be room left for your people.”

Bahloo ignored Edward’s warning, instead he pointed to the sky, explaining the constellations and how they came about but in general it was the darker patches between the sets of stars that held the most meaning for him. Then Edward realised there was so many similarities between their races, black and white and in general both wished for much the same. A simple life and the right to exist without obstruction.

As their camp fire died to embers, it was obvious Bahloo was to animated for sleep, so until the early hours he explained every sound made by every night caller and with his explanation he imitated their call and so exactly he would instantly be answered by the caller.

“What is your family totem?” Edward asked.

“It is the Coolbardie.” Bahloo proudly answered.

“I don’t know that name.” Edward admitted and Bahloo commenced to whistle a sweet tune.

“Ah it is the magpie.”

“No it is coolbardie – Bahloo don’t know magpie.”

“Magpie is what white fella’ call your coolbardie.”

“I don’t like white fella’ word.”

“I agree Coolbardie is much nicer and I guess that is why you are so talkative,” Edward laughed.

Bahloo continued with his dreamtime story, “coolbardie sings in the morning to let everyone know their important roll in creation.”

“I like that but I think we should get some sleep.”

Bahloo appeared puzzled, “what is Edwa’s totem,” he asked.

“White fella’ don’t have totem, could have a long ago but now they have their gods, something like your spirits.”

“That’s not good you must have totem or people marry wrong.”

“Possibly that is why we have family names, I guess your people’s totem is like our family names. My name Edward means prosperous and protector but I haven’t any idea where my family name being Buckley comes from.”

“Funny name,” Bahloo laughed.

“Goodnight Bahloo.”

Mid morning they were approaching the area the natives called Katoomba and were surprised to find in such a short period of time a small settlement had been established, with its back against the escarpment and its backyard viewing the Three Sister monument.

Edward quickly moved on as he wished to arrive in Parramatta within that week as he felt an urgency he could not explain, Bahloo picked up on Edward’s urgency.

“What’s matter with Edwa?” he asked as the descended down towards the coastal lowlands.

“Why do you suggest so Bahloo?”

“Bahloo know Edwa, something wrong, we blackfella’s say someone is walking with our ancestors.”

“There isn’t anything wrong but we have a similar saying, being walking on one’s grave.”

“How do Gubba walk in the trees?”

“No Bahloo we bury our dead in the ground.”

“Don’t bad spirits get them in the ground? In the trees the wind spirit looks after them.”

“Maybe there are good ground spirits that look after our dead.” Edward mused.

“Bahloo still say something is wrong with Edwa.”

“Only a feeling I have that something is wrong, I can’t explain it so,” Edward drew a deep breath, “I guess it’s nothing.”

“Edwa should ask the wind spirit,” Bahloo suggested.

“I have no spirits Bahloo, not even a white man’s spirit, so best you ask for me.”

Bahloo twisted around in his saddle and cast his gaze into the tall trees on either side of the road, “wind spirit not around.”

“Then later my friend, I’m sure it will pass.”

Once at Parramatta Edward discovered Macquarie was in town at his country residence, therefore he decided to attend to business before travelling to visit Sam. For once it was simple as there wasn’t any guard preventing his entry. Approaching he dismounted and had Bahloo mind the horses, at the door he knocked and to his surprise, no servant but Elizabeth Macquarie answered the door, recognising Edward immediately she inviting him to enter.

“Have you come from across the mountains?” She asked.

“I have but rested before Katoomba overnight.”

Lady Macquarie noticed the black lad perched high on his mount, she smiled but didn’t comment. “Mr. Macquarie has heard good reports about your farm,” she offered as a maid scurried across the hall and apologetically took responsibility for not being present to attend to the door. “That’s alright Joyce you keep doing the rooms.” Once again the maid scurried away like some tiny timid marsupial mouse while mumbling her incompetence, more out of avoiding an ill wind that may rise from her oversight of duty than true remorse.

“Would you like refreshments, I can have the cook prepare something.”

“Not necessary Mrs. Macquarie, my fiend Bahloo gathered some bush tucker earlier.”

“Bahloo,” she said while giving the black lad a second glance.

“Yes he is from the local lot near Mr. Wilcox’s farm.”

“I should think it isn’t a social visit Mr. Buckley.”

“No I have come to register a further claim and ask the governor for a little advice.”

“You do realise you can now register selections at the office in Katoomba.”

“Yes but it is the advice that is most paramount and possibly in the Governor’s interest.”

“One moment, I will see if he is busy.” Elizabeth left Edward in the hall and passed into another room. She closed the door behind. Some time later she returned, yes Mr. Macquarie will see you now but can only give you a little time as he had been invited out to visit the Macarthur’s at Elizabeth Farm.”

“That could be interesting,” the words slipped past Edward’s guard and to his surprise the woman agreed, releasing a slight titter but soon returned to her insouciant persona.

“Edward waited a moment before softly knocking.

“Enter,”

The door squeaked open and Edward stood silently awaiting response. This time there wasn’t any secretary to hover over his entry but as usual Macquarie sat pondering over reams of viceregal papers, with relief for a moment’s break from colonial business he forced a rare smile.

“Well if it isn’t the budding sheep farmer in person and by accounts doing quite well.”

“Quite well sir,”

“What can I assist you with?”

“A claim to an adjoining selection of land, I have the design and measurements with me.” Edward withdrew the intended claim from an inside pocket and passed it to Macquarie who took his time examining the document.

“It seems in order, do you have a copy?”

“That is the only copy sir.”

“So leave it with me, I will have my secretary process it when I’m back in Sydney but you will have to wait,” the governor paused then continued; “there is a mail service to Bathurst now so I will post it to you.”

“That would be most kind of you sir.”

“What this country needs is more men who are willing but Elizabeth tells me you have need of some advice.

“That I do sir,” Edward lowered the saddlebag from his shoulder and with permission placed it on Macquarie’s desk, the man leant forward as Edward lifted the leather strap and produced a number of gold nuggets which he carefully placed on the desk. “We have found gold on the selection but haven’t told anyone, I wished to ask your advice and if possible how we can sell it without starting a stampede.

“Wise lad, a gold rush is the last thing this colony needs at this point in time, especially with more convicts that free settlers.”

“That was my thought sir,”

“Will you promise me not to do anything or tell anyone?”

“If that is your wish Mr. Macquarie,” Edward agreed.

“It is more than a wish Mr. Buckley, it is a command but I can help you with another matter.”

“What would that be sir?”

“If you wish to sell your gold, I can put you onto a colleague who I can trust to remain discreet but it will have to be a little at a time and at a much lower exchange than the London market.”

“I would agree to that,”

“What about you partner will he agree?”

“Yes most certainly he will.”

“Also to say nothing?” Macquarie continued.

“Again I guarantee Hamish is well trusted.”

Macquarie retrieved a small note of paper from a draw and wrote some words. He passed it to Edward, “you give this to Mr. George Rogers at that address in Pottinger Street and he will put you right. But now time is pressing and I must be away.”

“I believe pressing business with Mr. Macarthur?” Edward gave a knowing smile.

“Business is appropriate but I shall leave it at such.”

Bahloo appeared most animated as they approached the elbow along the branch creek, describing his memories as if they were dancing there before his eyes like brolga cranes dancing on some floodplain. As they approached the farm the animation diminished as the memories of that day, when many of his family had been taken from him by a callous attack on his camp, crept greedily over happier thoughts of being with Edward as he worked Sam’s field.

Approaching the gate the figure of a young man close by the house could be seen but not Sam. The time was nudging past midday meal so it was expected Sam could be inside preparing lunch. Through the gateway Edward called and waved. The young man approached down the path. “Piers you’ve grown, I can hardly recognise you.”

“Edward and who is that with you?”

“You remember I spoke of my friend Bahloo?’

“I do and you did most often,” Piers gave a gentle nod.

“Where’s Sam?”

“Taken to his bed with some illness,” Piers held to the reins as Edward dismounted.

“How bad is he?” Edward followed Piers into the house.

“One day fine, another he can’t get out of bed, today it is the latter. Sam said it is swamp fever.”

Edward had heard of such but knew it to be a general terminology for who knows what to call it but I feel terrible.

Sam lifted his head and smiled as Edward came to his bed, “well I’ll be buggered at last a visit,” he weakly spoke, lifted his hand but strength failed and it fell back to the bed.

“What have you done with yourself?”

“Swamp fever, I came down with it a couple of weeks back but give me a day or two and I’ll be fine.”

Piers cut across Sam’s assurance, “I wanted to take him into Parramatta to the doctor but he won’t have it.”

“That’s Sam, independent to his boot straps.”

“I can’t run the farm on my own and wild dogs got into the chickens and went amuck, killed most of them,” Piers answer displayed a high measure of distress.

“Sam it is about time you gave up this useless plot of land and come out with Hamish and me,” Edward turned to Piers, “you as well young fellow, we have more than doubled our run and could do with an extra pair of hands.”

“I would like to do so but I won’t leave Sam,” Piers answered.

“I would expect you to say that, so Sam what do you think? If you won’t think about yourself, than do so for Piers sake.”

It was some time before Sam answered, he looked towards Pies and could see pleading in his eyes, turning back to Edward he came to realise he would never make a go of it at the farm. “I guess nature has the better of me, both with the land and my body.”

“Than you agree?”

“I guess so,”

“I’ll have Piers take you into Parramatta in the cart and you can make arrangements about what to do with the farm – and see a doctor but before I can return back across the mountains, there is a little business I need to attend to in Sydney,” Edward turned to the lad, “Can you manage that?”

“I would have already done so before if Sam had been agreeable.”

“Righto I will collect you both in Parramatta in a few days.” Edward removed a money pouch from his pocket, “take rooms at the Cock and Hen and I’ll see you in a couple of days.”

Once outside Edward called to Bahloo, “do you want to visit your mob?”

Bahloo brought the horses up to the door, “na you lot are my mob now.”

“Do you want to wait with Sam or come into Sydney with me?”

“Bahloo no see Syney, I go Syney.”

Edward laughed but didn’t correct the lad, “then Syney it is.”

The road to Sydney was busy with business conveyed to the new settlements. Parramatta, Windsor, Richmond and Liverpool were all expanding at an alarming rate and in demand for produce and luxury products. Edward smiled on seeing a cart with a single item, a piano, while others had furnishings fit for middle class English houses, often to be displayed on dirt floors against canvas walls among the dust, bush rats and termites, without mentioning dryrot and rising damp.

Along the way there were many fine houses, often set back from the road with leading avenues of European trees, their upper floors displaying pane glass windows, surrounded by English gardens, with English flowers struggling in the change of climate as convict servants attending to their growth, while folk with little breeding than that of a pig farmer or maidservant sat on shady verandahs, sipping cheap claret as if it was the finest French wine.

“What do you think of all this?” Edward asked Bahloo as they past one such estate and waved to the folk in the field and those at the house. Those bonded to the field favoured the distraction and waved back, those at the house remained ridged as marble statues.

“Bahloo don’t like houses.”

“I guess not and I should think it would be the same to ask me to live in a humpy. We know what we know eh Bahloo.”

Once in Sydney Edward took a room at his usual tavern but was quickly informed that the blackfella’ could sleep in the stable with the horses.

“He is a free man like the rest of us,” Edward protested.

“Then show me his ticket of leave,” the inn keeper demanded.

“Is Rosie around?” Edward thought if he spoke to Rose she would be more sympathetic, allowing Bahloo to bed down in his room.

“Rose has gone I’m the innkeeper now and I’m not having some savage stinking out my rooms.”

“You will have to sleep in the stable,” Edward advised the lad in language.

“Bahloo sleep in stable, no like house, Bahloo look after horses.”

“What was all that clap about,” the innkeeper demanded not comprehending a word that was spoken between the two.

Edward answered with the proverbial tongue placed firmly in the proverbial cheek, “he said if it was good enough for baby Jesus to be born in a stable it would be so for him to sleep there.”

“It will be a shilling all the same and if there is anything missing, it will be added to your bill.”

Edward’s business in town was to visit a Mr. George Rogers Esq. a procurer of fine substance for the elite, also pawnbroker to the down and out and sometime fence but in the words of Macquarie a man in whom he could place his trust.

The establishment on Pottinger Street was nestled between a millinery business and what appeared to be a brothel and although it lacked quality on the outer, once inside was wall to wall finery and stunk of middle-eastern incense, the smoke slowly lifting from a jardiniere filled with sand besides the entrance.

Bahloo refused to enter believing the smoke was to ward off evil spirits lurking in the establishment. The shopkeeper met Edward before he could advance much further than the door.

“May I assist you young man?” the voice came from behind a large oak display case filled with moderately valued jewellery. Edward startled as a ruddy round face appeared out of the shadows.

“Mr. Rogers?” Edward enquired.

“Could be, if you are buying then it is so, if you are from the establishment then possibly not.”

Edward gave a wry smile, as knowing the Governor’s personality couldn’t believe he would associate with such a character. “I have an introduction from the Governor to your good self,” he offered up the letter.

“So you are servant to our fine Governor?”

“No sir, I have a sheep station across the mountains on the Bathurst Road.”

Rogers read the letter. “So you have gold for sale?”

“That I have,” Edward placed a saddlebag heavily on a counter top and withdrew some of the gold. The man quickly scrutinised the quality.

“This is alluvial, where did you get it?”

“On my property Mr. Rogers,”

“And you wish to sell it?”

“I do but Mr. Macquarie is concerned it will start a gold rush.”

“Quite so and neither he nor I would wish that, not with the balance of convicts to settlers as it is.” The man appeared most interested as he invited Edward to produce more of what he had in his saddlebag.

“On our kitchen scales there is three pound weight but that is with the quartz as well.”

“Do you know the price of gold young man?” Rogers asked and weighed the load for himself.

“No sir,”

“Fine gold is six pounds sterling an ounce, you have three pound seven ounces here I would surmise but I should think half a pound is quartz.”

“Our scales must be faulty,” Edward admitted.

“You do realise there isn’t anywhere here in Sydney to process ore and I would have to send it to my agent in London.”

“I thought as such by what the Governor said.”

“I couldn’t pay you six pound an ounce, only a fraction of that.”

“I’m not a greedy man, a fraction would do fine.” Edward was becoming quite excited.

“Another point, I wouldn’t be able to give you it all in cash, I would have to support a promissory note for the bulk of it, made out to the newly established bank of New South Wales.”

“Again sir that would be fine;”

“Is there more gold?”

“I should think so,”

“Then we will make a gentleman’s agreement, you supply what you can and I’ll have it sent to my agent in London all without a word to anyone, is that clear?”

“Quite clear Mr. Rogers as demanded by the Governor himself.”

“For this kind of dealing, you may call me George but again we must be silent on the arrangement.”

With business complete Edward turned his attention to the multitude of strange objects within the shop, finding it a world of unknown quality. Some items he knew but had never touched, others he was lacking even the slightest understanding of their usage. “Have you something a woman would like?” he asked.

“Most things lad, is it for your good woman?”

“No my partner’s wife, I should take something back for him to gift to her.”

“What is she like, a simple country woman or one with some social understanding?”

Edward laughed; “she has the touch of finer society but there is none where we come from and our closest neighbour is fifteen miles away.”

“Possibly this?” the dealer collected something appearing to be a small blanket and placed it on the shop counter.

“It appears to be a small blanket.” Edward clumsily described.

“It it obvious you don’t have the breeding of your partner’s good woman. It is a shawl made from the finest mohair from Afghanistan. I won’t attempt to educate you where the country is. Feel its softness.”

“It is soft as silk.” Edward admitted.

“Have you ever felt silk?’

“No sir it is but an expression – what is the price.”

“For you nothing but don’t forget out deal.”

Back in Parramatta Sam was improving but remained weak and tired, he had left the sale of his patch in the hands of a local agent and was more than ready to travel west with Edward. It had become obvious he could no longer run his land by himself and Piers, although growing stronger with the work at hand was not a farmer and would never be so.

The following day they returned to the farm and gathered Sam’s belongings and after giving the few remaining fowls to a neighbour, loaded Sam’s old cart and commenced their travel back across the mountains.

With one final glance while passing through the gate Sam spoke, “Do you remember the day you left to find a passage through the mountains with Mr. Blaxland and the others?”

“I do Sam but now it seems as if it were another life and I another person.”

“Yet it was no more than three years and now you are to be my master.”

“Almost four Sam but never master, you are more than that to both me and Hamish and we owe you more than you could realise.”

“Possibly so but I feel I will be a burden.”

“There will always be something you can do, make those wonderful stews you were so good at.”

“I wouldn’t say wonderful.”

“When a man was hungry Sam they were wonderful.”

The path west to Cox’s Road was quite damp and the cart slid somewhat, bogging down on the occasion but by the time they reached the main road it was dry enough to travel with ease.

“It has been extra wet since you left and we had the creeks up, they even got old Ben Dansard’s flat-bottom past the sandbank near the elbow without dragging it.”

“It’s been dry out west, there is a word coined for it, they call it drought, something we never heard of back in England eh Sam.”

Sam turned to Bahloo, “and look at you young man, all grown up and riding a horse.”

“Bahloo good horse rider.”

“He stays on Sam and that’s the most of it.”

“How many sheep have you now?” Sam asked as they reached Emu Crossing.

“Many hundreds I expect, I’ve never counted them but the wool clip is bringing a good price even if we have to wait months for payment.

“You will have to get Bahloo to count the sheep.” Sam suggested; “hey Bahloo are you any good at counting sheep?” he called, bringing the lad to ride closer to the cart.

“I count sheep for Sam,” the lad eagerly answered.

“No good asking Bahloo to count sheep,” Edward quickly interjected.

“Why is that?” Piers asked as he cautiously drove the cart along its way.

“Blackfella can only count to three then it is simply many. I suppose the only counting they need is how many kids they have and then many would probably be too many – but he is good at shearing sheep.”

“Bahloo shear sheep.” the lad quickly answered in English.

“Your English is improving as well.” Sam praised.

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,234 views