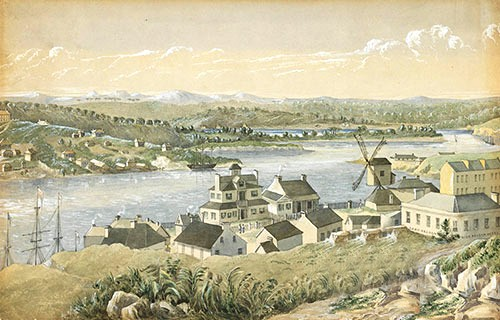

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 24 Jun 2019

The lumber for Sam’s new house arrived by bullock dray from Emu Crossing in the early afternoon, bringing the boys excitedly to help with the unloading. The delivery men stood looking towards the creek and the flood damage then the washout at the corner of the bunk house. The bullocky scratched at his grey stubbled chin and shook his head then removed his smoking pipe and plugged it with tobacco, “got a light?”

“From the coals in the hut if you wouldn’t mind Hamish,” Sam requested. Hamish soon returned with a glowing ember.

“I hope you don’t intend to build in the same spot.” The bullocky soon lit his pipe and drilled the ember into the damp earth with the heel of his boot, “can’t go about starting bushfires,” he ironically admitted as a foul smelling smoke wafted from his pipe.

“Not likely, Sam quickly related, “we are going to build further up the hill towards that stand of scrub.”

“Good idea, I’ve seen more destruction than you can imagine on the way over, all because people don’t think.”

“And I believe we have seen most of it floating down the river, what the hell are you smoking?” Sam demanded as he caught the acrid drift.

“Don’t rightly know; something I got from the blacks.”

“It smells rank, Edward go and get the man my supply.”

Edward returned with the small amount of tobacco in a leather pouch, the bullocky soon bumped out the native weed from his pipe. “Much obliged Mr. Wilcox as the government store holds most to bribe convicts to work and what they do sell to freemen is beyond my pocket – I’m not running you short am I?”

“No I don’t smoke but use it to barter at the market. You say there has been a number of drownings?” Sam asked.

“Four drowned at the Crossing you know and a few more below the milling camp and that young family with three girls they went, got them in their beds,” the bullocky refilled his pipe with Sam’s tobacco, while casting a dissatisfied eye towards his men, each turned away while pretending to work. Hamish returned with a second light.

“It was a wall of water, in some reckoning ten feet high, possibly more, they didn’t know what hit them; came out of the hills like an ocean. All much too flaming close to the river or built in a natural floodplain, can’t give marks for stupidity that’s all I can say.”

“True,” Sam agreed but in reality his previous choice was more luck than good management.

“Suppose I should be going,” the Bullocky said as he brought his three servants to order, “what are your lot like?” the man nodded towards Edward and Hamish.

“No they are both freed men.”

“It shows can’t get this flaming lot to work any faster than a slow walk, flaming useless, should give them back to the road gangs.” On hearing the complaint the three lowered their heads and shuffled their feet before falling in behind the dray. “Yea should be going, have to get back for another load for Robinson Flats.” The man cursed his bullocks and whipped the lead into motion. It slowly placed its weight to the yoke and drew forward. “With these flaming roads, won’t get there until tomorrow night.”

Once the delivery dray was on its way the three stood gazing at the lumber placed in separate stacks by size and design. By calculation it didn’t appear enough to build a shed never mind a house but the timber merchant promised it was enough to meet their desired plan.

“Hey you two as soon as the road is serviceable would you go into Parramatta, we need a number of things, Sam asked.

“It was alright last week?”

“It’s now closed over past the Watson’s, an entire section fell into the creek a couple of days back, was undermined during the flood and took its time giving away. Sam advised.

“Then I can find where Elsie has moved to.”

“I thought you already knew where she is?”

“Did, they have found a house of their own and are no longer with Henry’s brother.”

It was a warm early winter’s day. The nights were cold but with the morning sun the chill soon lifted. Sam was working in the top field while the boys busied with the foundations for the new house. The design was for four rooms, not large but sturdy with proper windows, even glass panels bought at expense on their last visit to Sydney Town and doors that kept out the draft and rain and with luck didn’t squeak on their hinges.

Occasionally Sam would raise his head and watch the boys at their work. Doing so filled him with pride and wonder how two men of totally diverse elements could work so close without conflict, one sober of thought and strongly leaning towards convention, the other embarrassingly open and obsessed with female parts and description of their usage.

Sam had once heard from an old Chinese market gardener of a belief called Yin-Yang, being for every positive there is a negative, from day there is night, from right there is wrong and opposing love there is hate. Hamish and Edward were as such yet fitted with each other as snug as gentle fingers in a fine leather glove, possibly their difference was the reason for fitting so.

With his thought on the two and his eyes on their working, Sam failed to notice a figure stumbling out of the forest close by the swamp. Eventually he caught movement and turned to find a young lad travelling towards him and seemingly without purpose. “Are you lost?” Sam called but the lad appeared not to hear while keeping his slow gait directed towards the hut. Sam approached, “are you lost son?” he repeated. As he spoke the lad collapsed to the ground in tears and exhaustion.

By his appearance the boy had recently waded through a swamp of mud that in the sun had dried to cake his skin and scant clothing. His shirt torn to tails and trousers holed so badly they scarcely held together or covered his vital person.

“What’s your name son?” Sam asked while attempting to comfort the lad.

“Piers Bradley,” the lad gave whimper.

“How old are you Piers?” Sam showed concern for one so young and apparently lost.

“Almost thirteen sir,”

“Where are you from?”

“Up-a-way beyond the timber camp:”

“And where are your family?”

“Gone sir in the flood, dad tried to save mother but both were swept away.”

“That was some time back, where have you been?”

“Travelling sir, I found some food from the farm before leaving but since then I have been mostly lost.”

“Have you other family?” Sam encouraged the lad to his feet and guided him down the hill towards the hut.

“None sir, dad and mother were sent from some place called Kent but I am from here.”

“Come on Piers you appeared starved; let’s get some tucker into you.”

It appeared the lad was Currency, born to convict parents in service and now he was alone in a harsh country without guidance or family. Being of convict parents gave him the status of a freeborn but unless a family was prepared to take him in, he would become another for the poorly run orphanage in Sydney, or farmed out to some settler who would work him hard and respect him little.

“What you got there?” Hamish called as Sam brought the lad to where he and Edward were working.

“His name is Piers; his family was lost in the flood.”

“And he’s been wandering for all this time?” Edward appeared surprised.

“It appears so, first things we should get him out of those rags, give him a wash and a feed.”

“He’s a little skinny I don’t think we have anything to fit him.” Hamish said while standing back to observe the lad and his long, mud caked obviously black hair, hanging like tails from his crown.

“I reckon we could cut the legs out of an old pair of pants and I have a shirt that – well will cover him at least.” Edward suggested being the smallest of the three.

“What are you going to do about him?” Hamish asked.

“He has no family and his parents were convicts,” Sam forlornly admitted as his mothering nature began to surface.

“Currency eh,” Edward smiled. He like the terminology, it set the newborn apart and gave ownership to this grand new land, breaking the ties to the mother country.

“Where were you headed?” Sam asked as Hamish brought water to wash away the mud while helping the rags from the lad’s undernourished body.

“Duno’.”

“Do you know where you are?”

“No sir somewhere along the creek,”

“I believe you should stay here, I’ll send word to the Chief Constable and see what he suggests. Would you like that, Piers?” Sam offered.

“Yes sir,”

Chief Constable O’Brien arrived some days later. He had placed no urgency on the lad’s plight, waiting until he had business along the branch in the form of hunting yet another bolter, as now with a way across the mountains discovered doing so was becoming most frequent.

Arriving at the Wilcox farm he soon noticed the construction of the new house. Riding up to where the boys were working he called.

“Pleased to see you have the good sense to be building away from the creek.”

Sam put down his hammer and approached the constable.

“Would you like tea Mr. O’Brien?”

“No thank you, I have pressing business, where is this kid you’ve found?” Sam encouraged Piers to come forward. Since the lad’s arrival a little colour had returned to his cheeks, even some meat on his ribs, yet he still appeared a pitiful site.

“What’s your name kid?” the constable asked.

“Piers sir,”

“Piers what?”

“Bradley sir.”

“And you don’t have family?”

“Not anymore sir.”

“What about back in the old country?”

“I don’t know sir, my parents never spoke so.”

The constable made a grunting sound and turned towards Sam, “I guess there isn’t much else that can be done except send him to the orphanage in Sydney and it is already at capacity; I’ll collect him on my return.” It was then Sam stated what had been in his thoughts since the lad’s arrival.

“I’ll take him on Mr. O’Brien, if it is lawful to do so, why with both Hamish and Edward soon moving on, the lad would be most welcome.”

“There is little law in that regard, the Governor creates what is necessary with each case and bases it on the poorhouses of home.” The constable released what could be mistaken to be a rare smile as he gazed down upon the unfortunate lad, “I can’t see any reason why not Mr. Wilcox,” the constable paused and addressed the lad, “that is if the kid is in agreement, what do you think Piers?”

“I would like to do so sir.”

“So it is settled, the kid stays here but I will expect the occasional report on his progress and if anyone comes to claim him, well you know how it works.”

It was therefore settled and by the simple mentioning of words, Piers was to become Sam’s ward and appeared contented with the situation. At Hamish’s suggestion for the present Edward should bring his cot into the bunk house and the lad could stay in the hut but with the completion of the new house there would be room for all. Again there was banter on snoring and smelly feet but both agreed it would be best.

Some weeks passed and the framework turned from clinker cover, to almost complete with little more to do than doors and windows. During that period Piers turned thirteen, he knew the month of his birth but not the day therefore one was supplied by Hamish. Not only had the lad become a teenager but he commenced to sprout, soon passing the nuggetty form of Hamish to almost as tall as Edward but he was a bean pole with gangly legs and arms, all topped with a black mop of hair that sat like some untidy bird’s nest upon a fence post. Piers had also settled into the farm as if he had been born to it, while his cheeky wit and eagerness to learn became most valued by Sam.

The week of Piers’ created birthday two objectives became imperative for Edward. Firstly he was ready to purchase his small flock of sheep, the more pressing being he knew very little about their care. Edward cursed himself for not thinking of the most important ingredient in becoming a sheep farmer earlier, realising his lack of knowledge was about to put back his plans, possibly even as late as the coming spring that would lead into the summer and not the best of time to be droving sheep over such a long distance.

Finally Edward’s concern turned to his friend Bahloo, he had often reflected on the boy’s brave action that had most likely saved his life. Now with the killing of the blacksmith well passed, Edward believed it time he visited his friend, as once he made the move across the mountains it may not be practicable to do so.

While discussing his journey with Sam, Piers entered into the conversation.

“I hear the savages kill people,” Piers nervously spoke his mindset on Edward’s safety.

“They can but in most cases it is we who kill them, I am known to the local lot and they have always treated me well,” Edward assured.

“What are they like?” the lad was growing curious but obvious his youthful head was crammed full of old world’s prejudice.

It was Sam who offered explanation. “They are like us in most instances Piers; they eat, laugh, enjoy life but on the whole are somewhat childlike.”

“Childish,” Piers stated resembling his parents using that word towards him.

“No childlike, simple living without the troubles we English folk seems to have,” Sam evoked.

“Childlike?” Pies repeated as if the word wasn’t sitting well with his understanding.

“I’ll put it another way, as a child you had dreams of dragons and castles and the likes.”

“Yes but I came to realise that they weren’t part of reality.”

“That is what I’m saying, reality destroys the dream, while with the natives and because of their primitive living they never reach that reality so remain childlike.”

“So they can’t think like us?”

“Of course they can but once reality arrives and takes away their dreaming there isn’t a great deal of difference between them and us,” Sam concluded somewhat assertively towards the invader’s behaviour.

Piers became bored with the conversation and turned to Edward, “can I come with you?”

“You can but it is up to Sam.”

It wasn’t difficult for Sam to agree to the lad tagging along as he trusted Edward’s judgement without question, also if Piers was to meet with the indigenous peoples he may divert from his growing distrust for them, possibly gained from listning to neighbouring farmers.

Setting out early the following morning Edward chose the route that passed by a neighbour Jim Claxton, a man who ran sheep. His intention being, if he were to approach Claxton, the man may allow him to learn as much as possible about the animal in a short period of time.

On reaching the Claxton farm his sheep were visible within a field of grass and scrub. It was then Piers spoke on the matter.

“Sheep don’t like scrub, they are pasture animals.”

“How do you know that, Piers?” Edward asked showing a measure of surprise as the lad had never mentions sheep before, possibly because Edward had never discussed the subject with the lad.

“My father was a shepherd for Mr. Reynolds before the flood and was a shepherd back in the old country.”

“What happened to Mr. Reynolds?

“All drowned; Mr. Reynolds his sheep and my mum and dad. I watched as the flood took them away and there was nothing I could do.”

“How did you survive?” Edward asked while realising it was a question not raised since the lad’s arrival.

“I climbed a tree; right to the top with the water at my feet and a big snake close by on a thin branch.”

“Weren’t you frightened?”

“What of the snake or the water?”

“Both,”

“I didn’t have time to be frightened and was much too choked to see my parents washed away, I heard mother scream for help and my dad attempt to swim to her but as he reached mother they were both dragged under and did not surface again.” Tears commenced to form but Piers fort them away.

“You shouldn’t have to witness such a catastrophe,” Edward sympathised as they spotted Jim Claxton working in his field. Edward called and on approach performed introduction.

“So young fella’ you want to run sheep?” Claxton was a weed of a man of advancing years, with a stooped back through a lifetime of shearing sheep. Edward admitted he did so and explained his position on the Wilcox farm.

“No good running sheep down there by the branch creek,” the man warned.

“Why is that so Mr. Claxton?”

“The land is much too wet, they will end up with footrot in no time at all, and the scrub is infested with ticks.”

“A neighbour has a few and we keep a couple.”

“A few possibly, but they would be kept close at hand not roaming the paddocks getting muck and burs in their fleece and my reckoning they don’t last further than the dinner table.”

“True,”

“When their fleece becomes infested with burs the clip is useless. If you’re gunna’ run sheep, it’s over the mountains where the land is more to pasture and dry. That’s where I’d go but I’m too old to do so.”

“That was my intention but I am still in need a few pointers.”

“A few pointers would be a start but as for learning, it’s taken me the best of forty years and I still know jack-shit. Tell you what lad you come by and I’ll do my best at giving you those pointers but my advice would be to try something else, ask Mr Blaxland, he’ll tell ya’ cattle is much easier.”

“That I have Mr. Claxton and he did.”

Later that morning the travellers reached the sacred grounds where Edward had previously attempted to climb a tree to find his bearings, this time out of courtesy he skirted the area. To go there once could be considered a mistake, twice may seen purposeful.

“Edward you appeared to take a long path to get somewhere you could have done so by crossing that cleared ground.” Piers observed as Edward made his detour.

“Native taboo only certain members of their group can go there.”

“Why?”

Edward thought for some time before supplying his answer; “are you religious Piers?”

“Yes, well sorta’,”

“What denomination are you Catholic of Church of England?”

“Church of England of course:”

“Would you go into a Roman Catholic Church?”

“No,” the lad was most affirmative.

“There is your answer, for you or I to cross that stretch of land would be like you going into a Roman Catholic Church. You wouldn’t do so and the priest would not wish you to.”

“Oh,”

“Where do the savages live?”

“Don’t call them that, blacks or natives, they are definitely not savages. It’s about half a day from here, should get there before dark.” Edward cast his eyes about the tall trees and undergrowth hoping to find a friendly face but this time they appeared to be alone, “if by chance some of the natives approach us out here, don’t panic and let me do the talking.”

“You know their language?”

“Enough to get by, there is one who speaks good English.”

“They can learn English? The lad appeared quite surprised.

“He’s a young fellow a Sistergirl but has a good ear for learning.

“What is a Sistergirl?” the lad asked. Leaving Edward nowhere to go except explain or change the subject, he decided to attempt explanation.

It took all of Edward’s powers to place the correct meaning into words but at length he believed the lad understood. The lad twisted his expression; half spoke then withdrew from doing so. Moments later the twisted expression returned, “Something like you and Hamish?”

Edward burst into laughter, “Like Hamish, heavens no he is much too crazy about girls to be considered so.”

“Oh I thought the two of you slept together.”

“In the same hut yes Piers but not together.”

“Sorry,”

“What would you think if it were so?”

“I wouldn’t care but my dad said men found beneath the blanket should have their nuts removed.”

“Is that your thought Piers?”

“Na they can keep their nuts, it wouldn’t concern me.” The lad thought for a time then it became obvious he wasn’t finished on the subject. “Edward have you been beneath the blanked with a girl?”

“I have,” Edward honestly answered, remembering his night with Nancy at the Cock and Hen.

“What was it like?”

“Aren’t you a little young to be thinking of that?” Edward asked.

“I heard Hamish talking about the ladies in Parramatta.”

“I think you should grow a little first, learn about things and listen to Sam, he will set you right.”

On dusk it became obvious they were coming close to the native camp as the light scent of burning eucalyptus leaves infused with the air within the forest.

“Not long now, are you nervous?” Edward asked, noticing the lad to be taking deeper breaths and holding for extended lengths of time, his eyes cautiously about.

“A little,”

“Don’t be,” Edward assured as they broke through the undergrowth into the clearing that was the native camp without notice, being an unusual occurrence knowing the native’s attention to environment and who was within it.

Their first encounter was with a number of the women, who on recognising Edward approached with smiles, “Edwa,” was spoken and repeated by the women.

“What is Edwa?” Piers nervously asked.

“That is their elocution of my name, now don’t you speak just remain by my side.” Shortly their arrival was noticed by an old man who quickly came to them and chased the women back to their work.

Edward recognised the native to be Manitjiman and a good friend of Deman and uncle to Bahloo. “Where is Deman?” Edward asked but Manitjiman turned his head without supplying an answer. Immediately Edward realised that Deman had obviously died as it was taboo to speak the name of those who passed. “What of Bahloo?” Edward enquired.

It appeared that after Bahloo had done away with the blacksmith and returned to camp with his story, they sent him across the mountains to be with others so the Gubba would not find him and the old man Deman had passed away around the time Bahloo crossed the mountains. As for Edward’s nemeses Balga, he had been killed in a raid on a homestead in the area beyond Emu Crossing. The more tolerant Wardan-noorn was now their elder, holding the opinion fighting against the invader was fruitless.

During the evening there was much conversation between Edward and Manitjiman and appreciation shown for the gifts he had brought but most of the attention was from the children towards Piers, as they attempted to pronounce his name, calling him Pas and laughing as they touched his mop of black hair, that untidy bird’s nest high on so fair a face, only to run and hide and peak at him from behind humpies.

“Are you still nervous?” Edward asked as Piers teased the children.

“Not any more,”

“The children seem to like you.”

“They seem real,” Piers commented as one boy stood before him, fixated with his fair skin. The boy reached across the short distance between, lightly touched his arm before running in laughter.

“They are real,” Edward enforced.

“No, what I was inferring, they are no different than white kids.”

During the early evening the two were invited to what could be described as a sing-song, which Edward found difficult to follow as it was mostly throaty sounds or words elongated well past meaning, becoming more the music than the verbal story, while the banging of clap or rhythm sticks, the gum tree leaf and sometimes the bullroarer, a length of wood on a cord swung above one’s head, were accompanying instruments. Although bullroarer was the European translation for the instrument, in English it translated to Secret-Sacred, meaning its name was not privy to the invader and mostly used in initiation and not general singing.

The singing lasted into the late evening when the men commenced to drift away to join their women and children within their crude bark shelters. As the last of the men left their night’s fire Wardan-noorn arrived and directed the visitors to a vacant humpy with Piers most amused with their sleeping arrangements.

The following day was allocated to the proud exhibit of new spears, nulla-nullas and boomerangs, explaining the family totems etched or painted onto each item, also the introduction to number of new members born to the clan, with Edward learning more language and teaching his. Edward also enquired on their intention to repopulate their old camp by the branch creek but to that there wasn’t answer, meaning to them that small section of their territory was now unspeakable.

Early on the following morning the visitors were ready to leave and were given guidance part of the way by two of the older boys, with the younger children running and skipping in the dust after Piers. Once past the initiation ground they were on their own and would reach home before the day’s end.

“How did Piers fair with the natives?” Sam had asked once alone with Edward.

“At first a little nervous but fine, the children loved him and he appeared happy enough with the attention,” Edward related.

“I was somewhat concerned about his developing bias against them being the reason for so quickly agreeing for him to go with you.”

“Ah, I guess that to be so. He did ask one difficult question.”

“Difficult Edward?”

“More a question I didn’t wish to answer.” Edward explained Piers’ suggestion that he and Hamish were, as Piers had said, found under the blanket and how he assured Hamish was most definitely a man for the ladies.

“Yes I think the lad is also developing along those lines, and I believe Hamish’s forwardness he guiding him along in that direction.”

“True and when I explained Bahloo’s disposition he did appear to enforce his preference,” Edward laughed, “it appears there isn’t much to teach him about the facts of life, or to point he knows the differences and where to put it but I much doubt he has ever seen a naked woman, although he did take notice of the bare breasted woman at the native camp.”

“You didn’t include yourself as such?” Sam asked.

“Nor you Sam, no I’ll leave that for his dad?”

“Dad?”

“That is how he perceives you now, so like it or not you have become his surrogate father.”

“Dad, oddly I don’t mind and truthfully feel quite proud of being thought as such but the suggestion does make me feel old.”

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,225 views