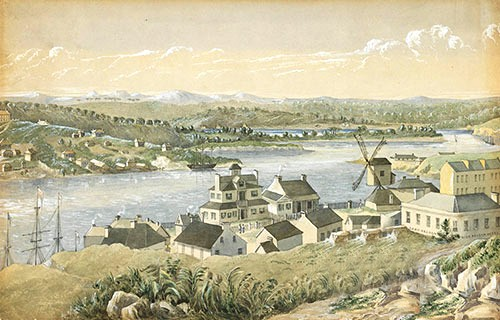

Sydney – Port Jackson – Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

Published: 29 Apr 2019

Life at the timber camp was harsh and harshest of all was Henry Perkins, not only was the man a drunkard but was endowed with a long sadistic streak that ran parallel to a yellow line of cowardice. He was a brave man with a whipping stick or musket in his hand but always stood back while allowing others to discharge the shot he had created.

Perkins had come to the colony as a free man but only one step ahead of the bailiffs for neglecting to pay his accounts and there was a suggestion of embezzlement from the family business.

In County Durham the Perkins family were famous in rare timber and cabinet making, with a royal warrant for their fine furnishings. It was this social standing that allowed Henry Perkins to escaped prosecution but after an affair with his brother’s wife he was quietly asked to leave the country, his fare paid but little more and if he were to return then all family ties would be forgotten.

During that very month there had been a death at the timber camp. A young prisoner fresh from the ship had come to Perkins with recommendations he had had timber experience back in his home county. Once at the camp it was discovered his experience was in fencing and had never taken an axe to a tree but was well skilled in digging the exact depth for a post hole and could wicker weave a holding fence like the best.

Perkins, instead of sending the lad back to barracks became most belligerent, forcing him to climb and trim a tree to be felled, an action that would normally be performed after felling but the timberman wished to view the newcomer’s ability to climb. The lad complained of dizziness but soon the birch sent him into the lower branches, after threatening even higher.

Plagued with inexperience and terror the young man fell and on hitting the ground was pierced through the abdomen by his trimming hook, he died on the spot. Perkins simply had his remains buried some distance past the latrine pit, while penning the report of negligence on the lad’s behalf to the authorities in Parramatta.

There had been no recurrence of trouble with the natives since the spearing of his dogs and hanging of the two captives by the military. Since that episode Perkins had obtained two more dogs but trained in bringing down a man and not game, while often bragging the next savage that came within cooee of the camp, would savour their bite. Spitefully that bite was trained towards a man’s most precious physical belonging and the animals would not release hold until those parts had become dislodged. Bring them on, he was heard say on many occasions, the next savage that comes near the camp will leave missing some vital parts.

Some time after the hanging of the two natives Perkins received a visit from a Sergeant Reynolds of the 73rd, who brought news to keep a sharp eye, as there was talk of continuing trouble with the natives. The timberman would have none of it, he had his dogs and a number of bush harden men, all trained in musket use. Nevertheless the sergeant repeated his warning while admitting he lacked men to billet any at the camp.

The soldiers returned back down the branch leaving Perkins in a state of euphoria thinking he could blood his hounds and add a few metaphorical black ears to his collection being the habit of some settlers when they encountered and shot natives considered to be pilfering or damaging crops. One such man had the notion to keep a plank outside his hut with the severed ears nailed tightly to its timber, his count was said to be eleven pairs.

It was past midsummer and the heat of day often brought both Edward and Hamish to the creek to cool after finishing their work. It had been some weeks since the manservant had his irons removed and he appeared quite content to remain at the farm, or at least held fear to do much else, so being difficult to read a man’s mind his satisfaction was taken as factual.

While immersed in the cooling water Hamish pointed to a sandbar up stream where the branch narrowed to half width and a passing skiff would need to pass in almost touching distance to the bank. “Look ahead!” he called to Edward, who had his back turned to the proceedings. He turned.

“What do you think?” Hamish asked.

“They aren’t local natives but they appear to be heading for the local camp, it’s a good mile up river.”

“Maybe one of those corroborees you mentioned.”

“Na wrong time of the year.”

“Then what?”

“Dunno’.”

Once the natives had crossed and melted into the tall timber the sighting was dismissed and Hamish appeared to have something on his mind.

“What do you do around here for women?” he coyly asked.

“Not a lot,”

“You know a man cannot live on bread alone.”

“We give you mutton,” Edward knew where the conversation was leading but chose to act dumb.

“What I mean is a man gets food for the belly but sometimes he needs to feed what hangs of it.”

“I do understand where you’re heading Hamish but it isn’t permitted for you to travel alone and I don’t think Sam will take you to town with that intention in mind.”

“You could take me into Parramatta sometime; I have heard there are a number of fancy women there.”

“They charge you for a ride.”

“I reckon I could sweet talk one into offering a sample.”

Edward laughed.

“What?”

“Just something I remembered.”

“Are you going to share it?”

“Nope,”

“Still I wouldn’t mind a night with one of those fancy women. An hour would do, no it’s been so long I should think it would be all over in seconds, probably spill my lot before entry.”

“That is too much information Hamish.”

“Surely you get toey and get sick of your hand.”

“You sure fire from the hip don’t you, have you ever heard of subtlety?”

“Nope, I’ve always thought it best to be direct and I’m getting a little frisky not to be so. If you not careful well you can guess where I’m heading.”

“Are you fair dinkum?”

“Fair dinkum what’s that?”

“Being real;”

“Na but I am getting a little toey, haven’t had sex since I left London.”

“I tell you what Hamish, next time we go in for supplies we’ll stay overnight and I’ll shout you one of your fancy women.”

“You mean that?”

“Wouldn’t say so if I didn’t.”

“What will Mr. Wilcox say?”

“Leave it with me but you’ll have to behave yourself.” Edward looked towards the sun. It was low and when it reached the crown of a large river gum it was feeding time for the pigs and chooks. He left the water, “come on pig feeding time.”

“Can’t,” Hamish remained neck deep in the creek water.

“Why not?”

“Just thinking of those fancy ladies has got me going.”

“I’ve seen it before come on.”

“Not like this you haven’t.”

“Right then you spank the monkey and I’ll meet you at the chook pen but don’t take all afternoon.”

Edward walked away laughing.

There was a nip in the morning air, somewhat rare for late summer and a light mist lowered into the timber at the logging camp. Henry Perkins was first up and stood at the edge of the clearing emptying his beer bladder onto the trampled bracken fern at the edge of the saw pit. He felt a presence behind, turning and with a long echoing fart acknowledged his foreman Bill Stubbs’ presence. “Tis the grog he offered as an excuse for fouling the air with his expulsions.

The camp commenced to rise and as the two continued their ablutions the smell of bacon filled the air.

“I love the smell of bacon in the morning,” Stubbs admitted and filled his nostrils with the aroma.

“Looks like rain Bill,” Perkins suggested and stood hands on hips, his pizzle still enjoying the cool air as the final drops descended. Perkins wasn’t a young man and was finding urinating most difficult as the years passed. Sometimes it came with a flow, others as if it banked up by some great earthen dam wall, and this was one such time.

“We have to get that last lot of timber ready for the bullock teams on Friday.”

“Shouldn’t be a problem if it doesn’t rain, if it does you won’t get the drays out for a weak.” Perkins supposed.

“If it rains the branch creek would be up and it would be quicker down river.”

“Hey Mr. Perkins your breakfast is ready.” The call came from cook who was already dishing out the meals. Both Perkins and Stubbs remained in conversation, neither appeared hurried to finish their urinating.

There was movement.

It was Stubbs who noticed first and reached to touch his bosses arm.

“What?”

“I thought I saw something.”

“Where?”

“Out there in the scrub,” the man pointed towards the shadows among the tall trees.

“I can’t see anything,”

“It’s there I saw something.”

“More than likely it was a kangaroo.”

Barely had the words been utter than a whooshing sound was heard and a massive dart pierced the air and with an almighty thud passed through Perkins large belly to stand at least a foot behind.

“Christ!” the man shouted and grabbed at the shaft of the spear with both hands as he fell to his knees, the force of the shaft hitting the ground pushed it further through his trembling body doing even more damage to the organs within.

Almost before he could realise what was amiss a second dart pierced the air, hitting Stubbs in the shoulder, a third ripped through his throat, rendering him speechless to cry a warning. As he fell to the ground a host of black savages came running hooting and hollowing murder from the undergrowth and within seconds fell upon the dozen or more workers as they settled for breakfast.

A number had time to collect their wits and reach for muskets, even get away some shot but mostly it was noise without much effect and within a matter of minutes the camp site was quiet, thirteen timbermen were dead or dying while only three of the natives had received wounds. As for Perkins dogs, much pleasure was taken in their despatch while still chained beside the man’s hut.

Friday’s bullock teamster came across the site and from distance he believed it quiet for a timber camp, usually the hollowing and chopping and sawing could be heard from the road as he reached the branch creek where the camp was situated. At first the bullocky though noting of the quiet, possibly it was meal time but his arrival was mid afternoon and all should be at their work.

At first glance all appeared normal but further in he discovered the workmen’s huts were burned, then he saw the bodies, dropped where they stood or sat eating their breakfast, while crows helped themselves to the carrion that were once the timbermen.

It took the better part of two days for Fed Hope to reach the military at Parramatta and another two for two squads of soldiers to reach the timber camp, coming across land instead of using the river, as on water they could be open to attack from the thick undergrowth along the branch creek. On reaching the site they found but destruction and decaying carcases of the timbermen and their animals.

Nothing had been spared dog, man or draft animal, all dead and decaying in the heat of late summer and the stench could be smelt almost a mile before coming onto the site.

“Righto’ down guns and let’s get this lot into the ground,” Lieutenant Brent Hemsworth called to his troop, while instructing vigilance and a placing a small guard on the ready against further attack.

There would be no reoccurrence the natives who enforced their displeasure had long gone, mostly to the man group some distance up the branch towards the foothills of the mountains. The few from the local camp had returned to their humpies and had all but forgotten their revenge. It had been done and they were satisfied their executed brothers had been atoned so it would be life as usual.

It was common among native tribes to inflict and eye for an eye, a wound for wound and life for life. Sometime within the heat of it all, more than equilibrium would be inflicted but if it were not too excessive was accepted.

True, two natives executed and game unnecessarily killed by dogs may not have equalled thirteen timbermen, seven dogs and six draft horses and oxen, not including the destruction of the huts and equipment but many of the tribe believed a few extra would attain for the many they had previously lost. For the indignation of sliced ears displayed as trophies and women held captive for backwoodsmen’s sexual pleasure and the sadistic castration of two of their youth by a vicious bolter with a lust for blood and depravity. They survived the menace but the bolter did not.

After attending to the timber camp Lieutenant Hemsworth lined his men and marched them down the branch towards the local native encampment. There must be retribution and he was the man and in the right mind to do so.

On reaching the native camp he found almost all of the men had either gone hunting or were visiting the main mob, while many of the women were foraging some distance away. Remaining at the camp was a number of children under care of the older women and some older men who no longer had the strength of body to join in with the hunt.

On reaching the edge of the clearing Hemsworth lined his men in single fire with muskets primed and cocked.

“Ready sir;” his corporal softly acknowledge, his heart beating a drum, his conscious against the call.

“Right on my order fire and remember none are to be spared, they must be taught a lesson.”

For a moment, an instant, there was silence but no order. Was there a miniscule measure of humanity within the man, could killing innocent women, children and men past their waring days be fair recompense for the slaughter at the timber camp. If there was a measure of compassion it wasn’t with Hemsworth or his troop on that day.

“Fire!” the man shouted, bringing attention to the camp and a state of panic. One reloading, a second reloading and few remained. Those still alive or wounded were soon dispatched at the point of a bayonet. And it was over.

“Did you hear musket fire?” Hamish came to the hut for lunch with that question. Sam thought so but Edward wasn’t certain, he looked to the heavens for storm but there was none. It was a clear day, the sky a gentle hazed blue from horizon to horizon while a light sea breeze took the sting of heat from the air.

“May have been from the timber camp,” Sam suggested.

“It appeared closer than the timber camp, besides I don’t think the sound would travel that far, especially with the wind from the east,” Hamish predicted.

“I couldn’t say, could be hunting and I did hear Jim Moss over at the bend was having problems with cockatoos eating his crop.”

“It wouldn’t be so Mr. Wilcox, if it were it would be single shots, what I heard was a number of volleys.”

‘A mystery then,” Sam concluded but it wasn’t done within his thoughts. Something was amiss. The land appeared quiet, like a funeral church choir without dirge.

During the afternoon the farmer visited his top paddock and listened for any sound from the native village as now that the wind had turned to the North West, their chanting and sounds of children at play should be clearly audible. He heard nothing. Back at the hut he approached the others.

“I agree, I don’t like it,” he said with a gentle shaking of the head.

“What don’t you like Sam?” Edward enquired from his lesson on reading while Hamish attempted to also follow his lessons, heavily placing his Geordie accent to the vowels.

“I’ve come from the top paddock and I can’t hear a sound from the camp.”

“Possibly they have gone to the main group,” Edward suggested.

“All – women children and old men?”

“Possibly,”

“I’ve never known them to do so before, besides they wouldn’t take the women and children.”

“I couldn’t say, it could be as Hamish suggested and they are having a sing song or at some other camp site.”

“What a sing song without singing or song, I don’t believe so, I think all three of us should take a wander over there before its dark. It doesn’t hurt to be sure.”

“We could go now if you like,” Edward agreed placing his reading aside.

As the three approached the camp they noticed a circling of crows above the humpies, riding high upon the thermals and all about remained the scent of spent gunpowder and sulphur and burning.

Breaking into the clearing that was the native camp the full extent became most obvious. There wasn’t a living sole; even the emaciated camp dogs were not spared. Women were felled still holding babies while others at their work. One old woman had been shot through the back, falling headlong into the camp fire burning away her body to the shoulders, while inside the security of humpies were the remains of infants, all suffering musket shot or gashed open by bayonet.

Edward went cold as he found the body of the one he called Polly. Polly and her happy face and childlike cheeky disposition, a woman who was harmless to anyone or anything that had a higher life force than a yam root. Beside Polly fell her friend he called Dot after his aunt back in Devon as she was quite rotund. Polly had a bayonet gash across her abdomen while Dot displayed a musket shot to the side of her head. Edward quickly gazed about, “Can anyone see Bahloo?” He shouted as the words choked in his dry throat, “or Deman?” They all searched about but neither could be found.

“What should we do?” Hamish asked not wishing to interfere with their dead ‘lest they be blamed.

“Who would have done this,” Edward asked.

“My guess it was the loggers.” Hamish gave reason.

“Has to be military, too much firepower for the loggers and the timbermen don’t use bayonets.”

“Why kill the children?”

“I couldn’t say,”

It was true, how could they know of the military’s reasoning, as the attack on the logging camp had not yet filtered down the branch creek and the military approached cross country to avoid ambush on the river.

“I think the main mob should be told,” the farmer suggested.

“Doing so may start a conflict that may wipe them all out.” Edward answered.

“If we tell them or not, there will be conflict but they have the right to know and bury their dead but I only know the direction of the others and not the location,” Sam took a deep breath as the reality of the situation choked in his throat.

“I do, I went there once with Bahloo,” Edward admitted, “I’ll go and find them,”

“It could be dangerous, I think you should not.”

“I’m sorry Sam I must.”

“Then take the horse,”

“I’ll go on foot as the terrain towards the camp is much too steep and the ground loose, I’ll leave with sunup.”

Early morning and with some trepidation Edward gathered a small supply into a bag and commenced to leave, making sure he included gifts to sweeten his message. Even by leaving early the journey would take most of the day and as he was somewhat unsure of the final section of the way, or what his reception may be and he didn’t wish to arrive in darkness.

On departing Sam grabbed his arm but neither spoke. Edward gave a slight nod of his head and was gone.

“Will Edward be alright?” Hamish asked once he had departed.

“I’m sure he will be as he is known to the local mob.”

“You should have sent me with him.” Hamish appeared to be genuine in his concern.

“They don’t know you and it may spook them.”

“Spook them? They don’t appear to be human enough to be so.”

“They are I promise you but haven’t the need for our so called modern ways. Given time they will become as us.”

The farmer gave a nervous smile as his thoughts remained with Edward and what his reception could be, especially after delivering his news. To break his disquiet Sam continued with the theme of Hamish’s interpretation of the blacks. “They make great horsemen you know.”

“Can they be house trained, we had a cat once and it shat wherever, had to keep it out of the house.”

“They aren’t animals, they are just like us but black and primitive but their minds work the same. The first governor, Arthur Phillip, had a young fella’ called Bennelong live with him in his house and had meals at his table. He even took Bennelong back to England with him to meet the King. Bennelong has now returned from his travelling and lives in the area.”

“King George must have been impressed,” Hamish laughed.

“Couldn’t say, have work to do the pigs won’t feed themselves.”

“I’m onto it boss.”

“I’ll give you a hand as it will take my mind off concern for Edward’s reception.”

The farmer’s unrest towards Edward’s safety remained as they walked towards the pen and continued through the feeding. Hamish wished to asked more but doing so was not his station. Although Sam had given him equal freedom as Edward enjoyed, Hamish still felt the chains around his ankles, his wrists and his heart. He had no wish to be returned to the barracks to be reallotted to one without humanity but his question was wearing away at his decorum.

“I do wish Edward will be alright,” the farmer sighed as his confidence waned while watching his breeding boar hog the bulk of the food.

“You really like Eddie?” Hamish bravely stated.

“Don’t ever call him Eddie he hates it so.”

“Alright then – Edward.”

“It comes from his home in Devon and someone he knew well called him Eddie so the name is reserved for that memory.”

“Someone he knew?” Hamish asked.

“Yes someone he knew. If you need to know more you speak to Edward.”

As they walked back to the hut the farmer spoke, “I’ll put you to ploughing this afternoon; have to get the top paddock prepared for planting.”

“Fine, I’ll harness Dobbin,”

“Dobbin?” the farmer queried.

“The new horse, you haven’t named it yet.”

“Oh I left it for Edward to do so,”

“He said it was for you to name it.”

“Oh well when he returns,” the farmer gave a long sigh as they entered into the hut, “Dobbin,” he smiled, I like that, it has a ring to it.”

“What will be planted in the top field?” Hamish asked.

“Again Indian corn, I should think as the ground is too harsh for wheat.”

“Back home we grew barley for the local brew house.”

“Don’t try that here with the maize, you’ll soon have the Johnnies after you,” Sam warned.

“Why would that be?”

“Because there isn’t enough grown for food as it is, if it is turned into booze people would starve.”

“If drunk at least they would starve happy.”

“What happened to your land?” Sam asked.

“We lost out to the landlord, he fenced all the allotments and threw us out, turned our small holdings into one large cattle run.” Hamish’s expression grew mean as he spoke.

“That was happening all over, even worse in Scotland I believe, in some arrears whole communities were evicted and immigrated to the Americas,” Sam agreed.

“What about here, do you think it will come to that?”

“I much doubt so Hamish, too much land not many farmers.”

That afternoon while drawing water for the vegetable patch, Sam noticed a small boat along the branch creek. He paused until it was close and waved. The single occupier brought his craft to the bank.

“Mr. Wilcox,”

“Mr. Wainwright what are you doing this distance up the branch?”

“Was delivering some supplies to the timber camp but it is no more.”

“No more what does that mean?”

“Gone – the flaming savages speared them all, there is a notice pinned by the military describing the fact.”

“When?”

“Dunno’ but ‘tis the same as I passed the black’s camp. Dead the lot of them.”

“I know that to be so,” the farmer was about to relate Edward’s journey but thought better.”

“Best I be on my way, you lot along the branch should be watchful once the main bunch get wind of it, you know what the blacks are like when they get their dander up.”

“Will do Mr Wainwright,”

That night Sam took a walk along the creek until he reached his favourite tree, a huge willow that drooped branches to kiss the water, while below was a dark tunnel where one could hide away from the world and on a summer’s day even a hot breeze appeared to cool under its shade.

Seated on the gently sloping bank he threw pebbles into the moonlit water and watched the rings spread ever out until they reached the far bank. ‘Life is a little like that,’ he sighed and thought of Edward. Past experience gave him confidence but their world was changing and who could say how natives may react. Moments later he heard something behind, he turned.

“It’s only me Sam, don’t panic.” Hamish softly spoke as he approached.

“Having a quiet thought Hamish,” Sam answered.

“Do you mind if I join you?”

“By all means pull up a seat.”

Hamish smiled and sat at Sam’s side, “you are still concerned about Edward?”

“A little, he’s gone through a lot.”

“Haven’t we all Sam and that I believe is what will make him strong.”

“A good point, tell me about home?”

From an English prison colony to one of the Great Nations of today. This how it started. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,211 views