Published: 25 Feb 2019

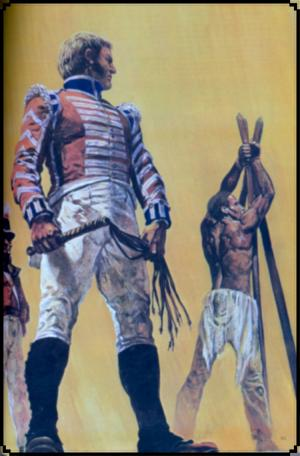

Picture from Australia’s Heritage Magazine 1969

“In the England of the Eighteenth Century being gay was a hanging offence but if one was fortunate, if it could be coined as fortune, transportation for life may become one’s redemption from the gallows.

“Port Jackson the out flung prison for the dregs of the British Isles may have made one shudder but if a felon had a measure of luck, good behaviour and working ethic, it could become an open sky far from the closed minds of British high society and without plan, or realisation from the planning fathers, New South Wales became the Social Experiment.”

The view of South Head shimmering in heat haze of a southern summer was a welcome relief for the crew of the Duchess of Devonshire, an aging twenty-four gun East Indiaman nine months out of Plymouth. It had been a rough passage, plagued with incident and accident but no worse than what many vessels experienced while travelling through those sparse, wild and mostly uncharted southern oceans, half a world away from the well travelled waters of Europe and the Americas.

Four of the Duchess’ crew were lost overboard during a ferocious southern gale, while losing part of the main mast less than two days out of Cape Town on its eastern run towards New Holland, with much of the supplies spoiled by salt as a hold cover came away allowing a great deal of seawater to enter below deck.

While returning to Cape Town a fight broke out among the ratings of the army relief for the Colony of New South Wales, over the winnings of some insignificant dice game. A knife was produced and one mortally wounded, ending with a ship deck court-martial and execution by rope.

Without further ceremony both aggressor and victim were given to the cold depth of the southern ocean, one either side of the ship so they would not have to rest perpetually together, being stitched into canvas with the last stitch through the septal cartilage of the nose to be sure there wasn’t life therein.

After a slow return to Cape Town and delay of some weeks the Duchess of Devonshire was once more at sea and once again hit by the rogue elements often associated with the Roaring Forties. Although this storm was not as devastating as the first, it did blow the ship off course and far to the south, to limp its way without the help of the prevailing winds that blew along the forty-ninth south parallel, leaving it to slowly progress through the northern reaches of Arctic ice and fog. Sometimes these conditions would last for days with visibility down to only yards, making it most difficult to see icebergs until almost on top of them.

Often a tower of ice would pass almost close enough to reach out and touch. It was such towers that concerned them the most, as it was well documented only a portion of ice was visible above the water, below could be a jagged shelf of waiting destruction and any sailor who may have survived such past catastrophe, would still hear the howling of timbers as they once again came into contact with these white-blue silent lifeless megaliths.

Scurvy and dysentery from bad hygiene and cramped space had also become apparent amongst the two hundred and seventeen prisoners stowed below deck, with the death of twenty four otherwise strong young men and seven convict women, one woman during child birth with the child stillborn.

Even the crew failed to escape the dreaded disease and three sailors were also given a sea burial with the deceased prisoners. The sailors only privilege being they were wrapped and weighted before given to the deep by a gathering of their compatriots with a prayer and collection for the widow while the convicts, stripped of their clothing were unceremoniously dumped over the side to float in the wake of the ship, becoming food for sharks and fish.

Not until sighting and passing of Whale Head and South East Cape at the southern tip of Van Diemen’s Land was their belief in survival or any chance in reaching their destination realised but with a thousand miles of open water yet to travel and the danger of the Furneaux Islands at the north east of Van Diemen’s Land all knew a keen eye, a good wind and a prayer against further storms was required.

Captain Albert Johnson was a pragmatic man and not one for prayer or humanity. It was his position to transport his lot of two hundred and seventeen men, women and a number of children born during the voyage, less those already given to the ocean, to New South Wales at one guinea a head. A high price for that time, offered with the hope paying a premium would encourage captains to take more care with their charge, being so for in the past, as with the Duchess of Devonshire, the toll had been extreme.

What those in Whitehall failed to realise being, Captains were paid on convicts loaded and not on delivery in New South Wales, there stood the flaw in their philosophy, as loss of life during the voyage became incidental and without influence on their profit. As for supplies, which was to be extracted for from the price per head, even less attention was taken towards the needs during such a long journey and what was loaded was often of lesser quality, spoilt by rat faeces and weevils or so poorly stored that one product tainted another. Much needed space for supplies was often taken with goods with high resale value once landed at Port Jackson.

The run around Van Diemen’s Land went without incident but on reaching Point Hicks, on the south of the New South Wales mainland the ship’s passage was interrupted by yet another storm, churning the guts of convict and crew alike, with the loss of three more poor wretches taken by dysentery while many others were barely alive, so with the sighting of South Head and entrance to Port Jackson a sigh of relief lifted from both convict and crew, then with the calm waters of the harbour and the smoke haze from Sydney Town not too far ahead, cheers and laughter developed, even from those poor wretches whose future was undefined.

Once within the calm waters of Port Jackson an eerie silence fell over those on board. During the crossing survival was foremost, now with the vision of Sydney Town carved out of the eucalyptus wilderness of the southern land there was time to reflect on an uncertain future, of slave labour and savages who to a man believed enjoyed human flesh. Almost a single redemption, being the fallacious belief beyond the blue hazed barrier some distance behind the settlement could be found China and the Orient.

“Ahoy there Duchess of Devonshire,” The cry came from over port bow, bringing Captain Johnson to hang precariously over the bulwark almost loosing his hat of rank but saved by a quick think rating.

Below he discovered a whaling boat carrying some mid-ranking officer of the Seventy-third Regiment of Foot, while bobbing up and down within the ship’s wash and having difficulty in keeping from falling into the churning sea about.

“You seem to have lost your sea legs my good fellow,” the captain censored, somewhat entertained by the man’s lack of balance.

“Too long on land I’m afraid.”

“What be your problem?” Johnson crudely enquired as the small craft closed in, hitting the ship’s hull with a loud wack, sending the visitor arse first to the decking of the whaling boat. Awkwardly he rose again to his feet, while dislodging the wet from his behind with his hands and cursing boisterously towards his oarsmen for their carelessness.

“You appear somewhat damp my friend,” the captain jovially called.

Somewhat embarrassed and ignoring the captain’s assumption the man answered. “Jim Wilborn – it will be, I’m here as pilot to guide you into port.” As he spoke one of the crew threw a Jacobs Ladder which the pilot caught, placing his shoe in the lower footing he commenced to climb on board, while the heave of the ship threw him awkwardly against the ships side. Cursing he continued his climb.

“The name’s Johnson, then welcome aboard Mr. Wilborn but I have no need for a pilot, this is my third visit to this god-forsaken arse end of the world, so I surely know my way,” Johnson shouted back, displaying a rare measure of joy, for as soon he could be rid of his charge, he could return to England, on way collect a load of tea from the orient for the thirsty rich of London, before recommencing his profitable trade with the newly proclaimed American Republic.

“All the same Mr. Johnson it is my duty to do so and many a captain has uttered those very words, only to come to grief and by the looka’ ya’ you’ve already had your share of that.”

“Too true Mr. Wilborn,” Johnson agreed as the official inelegantly climbed aboard.

“What’s your cargo?” the pilot asked casting his gaze across the ship’s emaciated crew and the small number of convicts allowed on deck for exercise. “By the look more flaming convicts,” Wilborn answered his own question, “as if we don’t have enough already,” but it was the man’s duty to guide the ship to dock, not comment on its cargo, so he soon turned away from the wretches on deck to the job ahead.

“I can’t say much about that Mr. Wilborn. It is my job to transport them here and once done they are your problem.”

“You’ve had sickness on board?” Wilborn asked noticing the sorry-full state of both crew and convict alike.

“Some Scurvy in the main,”

“I thought after Cook, you navy lot had worked out the cause of that problem.”

“I can’t grow lemons at sea Mr. Wilborn, nor control God’s heavens.”

“Righto Mr. Johnson, as you know your way, I’ll take a pace beside and be able if needed.”

“Take her in Mr. Elshaw,” Johnson called to the helm and stood upwind from the smell of his human cargo, “You never get use to it,” he bitterly complained as Wilborn came to his side.

“What would that be Mr. Johnson?”

“The stench of sick and shit and even after scrubbing the old tub down it remains soaked into the timbers and calking, the old tub will go to the breakers still smelling of death.”

“I’ve seen the Duchess before,” Wilborn commented while watching the southern swell as it forced further past South Head.

“Her third voyage carrying convicts I believe and I think the shit and piss from her first is still permeating the planking.”

“I seem to remember another Captain, a Joseph Brennan if I recollect correctly, a right religious man there never was but as cruel as one could be on his crew and convicts alike.”

“True this is my first with the Duchess, Brennan was killed when attacked by a French frigate off Cadiz, he was master of a coastal schooner called Spirit of India at the time. I believe he refused to allow boarding and was fired upon.”

“A true king’s man to the end,” Wilborn admired.

“A true fool ‘tis my estimation Mr. Wilborn;”

As the boarding plank was lowered at the Sydney Town dock, a number of folk came down to look over the new arrival, or more to fact break away from the mundane drudgery of their day’s duty. Among the onlookers there were convicts in irons, scheming how they could somehow stowaway with the ship’s departure and be gone from such a wretched country, convict overseers with foul tongue and stinging birch, scantly dressed women doing their trade as washer, maid or prostitute and a number of children. The children mostly born to unwedded convicts and as mistrusted as their parents, while those audacious progeny neither belonging to the colony or their parent’s homeland, had become the unintended product of a social experiment.

With his work completed Wilborn shook Johnson’s hand as he commenced to disembark, “then I’ll be on my way, normally the Governor meets any new arrivals but he is out at Liverpool Plains, some problem with the blacks, there was a spearing of two convicts looking for native tea, a third, although wounded, brought back the news but has died since.”

“Bligh?” Johnson suggested, remembering the troublesome man he had encountered on his previous visit, when after an altercation about landing rum, was all but frogmarched by the Governor’s men down to the docks, placed on board his ship and left guarded until departure. Oddly those same soldiers who marched him to his ship soon purchased his rum at far less than he had paid for it. With the memory came also that of Bligh’s language and never had been heard a more foul a mouth or fired temper but given a moment Bligh would once again settle into his solemn normality as if such an incident had not occurred.

“No you have been away for a while. Lachlan Macquarie is the governor now; Bligh was recalled, as was the New South Wales Corpse, too much graft and rum, unlike Mr. Bligh, Macquarie is military and not navy and not slow in drilling you until footsore.”

“I’ve been on the New England run of late so haven’t had much news about these parts; I do have a small cargo of rum to sell,” Johnson showed concerned, “my belief was rum remained currency in the colony,” he spoke without placing emphases on his argument, not wishing to be once again at difference with yet another governor.

“It remains so in part but must be sold through the Government Store, no more free market like under King and Bligh and the officers of the naval corpse. Macquarie isn’t a bad bloke but much too soft on the convicts, too many tickets of leave issued to the waste of the earth. He thinks he can make something of this place, it is even spoken he wishes to rename it New London.” Wilborn gave a quick nod of the head, a dismissive wave of hand across those gathered and departed.

“Then I wish him luck Mr. Wilborn,” Johnson called after the officer.

Without turning Wilborn lifted his hand in friendly gesture above his head, “he will be in need of it Mr. Johnson, yes he will need it and that is a certainty.”

For some time Johnson stood in scrutiny of the colony. It was true since his last visit there was new order within the town while showing a measure of permanency, even prosperity. Mostly gone the scattering of huts and tents, replaced by an number of streets and lanes with brick and stone structures equalling any he had encountered in the Americas’ but lacking the gentle folk of breeding and fashion about the street, replaced by ragged fellows with hapless expressions and indefinite futures.

“Mr. Ferguson!” Johnson called for his boson while disengaging from the view. Ferguson approached and waited instructions.

“Right then start unloading this scruffy lot, I want them all away and below deck hosed out before sundown.”

“Hoy there!” The call came from the base of the gangplank capturing the captain’s attention. “Rubin Bastion, His Majesties Customs for the colony of Port Jackson is my profession, to inspect your cargo before offloading is my demand.”

“My cargo is convicts sir and you may inspect them as they disembark.”

“What was your last port?”

“It was Cape Town Mr. Bastion.”

“No coolies on board?”

“None at all sir only the dregs of the British prison hulks.”

Without invitation Bastion came aboard, his eyes everywhere, his suspicions ramped, “contraband?” he simply asked.

“What do you include as contraband Mr. Bastion?”

“That depends,”

“I have a small cargo of cotton cloth from Manchester mills, tea and some rum for trade.” The captain truthfully but cautiously answered.

“Ah rum you do realise it must be sold through the Government Store?”

“So I have been advised by your pilot Mr. Bastion.”

“The other can be through any one of the merchant houses.” The man looked towards bow then to stern and implied permission to continue down through the lower decks. “Rum,” he said as he advanced, “are you a drinking man Mr. Johnson?” the custom’s officer paused his progress.

“Moderation Mr. Bastion, as any god fearing man should be.”

“The scourge of this place is rum.”

“Fine whiskey is my choice,” Johnson answered as he followed down into the darkness below deck.

“A fine whisky is rare in these parts Mr. Johnson, yes rare indeed.”

“I do have a generous supply myself.”

Bastion paused, “I would think for a bottle or so, a man wouldn’t have necessity to dig further into an honest man’s privacy.”

“I would be most please to share my supply with such a fine gentleman as your good self?”

Soon the custom’s officer was satisfied and while supporting a package wrapped in cloth prepared to conclude his business. He lent in towards Johnson’s ear, “William Blackamoor at the Goodfellow Warehouse for the other, mention my name and he’ll do right by you.”

A small crowd had gathered to watch the unloading of the poor wretches, who once on the dock lost their sea legs. Many finding it almost impossible to retain their stand, while bloodied, iron chaffed and dissolute from hunger and lack of hygiene they attempted to retain some measure of dignity; with heads bowed and all signs of human activity dismissed from their countenances.

A number appeared too unwell to attempt to hold their feet; with two collapsing to the mud unable to rise again even under the sting of birch, their first glimpse of their new prison was to be their last, as death became the redeemer.

Those who held their stand appeared bewildered with what they discovered, believing they had been delivered to hell itself for such petty felony. In many cases being the crime of attempting to survive, thus stood otherwise innocent men who giving proper chance would have been law-abiding citizens of a gentle realm but England could not be described as such.

The gathered crowd closed in, convict, emancipists and freeman alike. Women with small children tittered at the newcomers’ almost naked state and wretchedness while covered with sores and their own excrement. Many remembering only a few short years hence, even months, they were gathered on that very spot, conveying the same thoughts and terror. Now through enterprise, graft and cunning, some had become almost free settlers but never allowed to forget their past, carrying the stain of emancipation as if tattooed on their foreheads, their crime forever on the lips of those considered free settlers.

A young boy, no more than nine years of age, broke through the crowd of onlookers and stood before the newly landed convicts, his mouth ajar and eyes as wide as a wild animal in fright. “Come away Tommy,” the voice of a woman called from the crowd, bringing the boy back to safety in a dash.

“Ma he is all bloody,” he innocently cried as he gathered around her skirt.

“He won’t hurt you boy,” the woman promised.

“What is he ma?”

“Only some poor man on his downers, now get you going home and tell your father I’m be along shortly and tell him to keep of the grog or there will be trouble.”

“Come on you lot, it isn’t a circus get about your business.” An officer of the 73rd. growled while pushing back the crowd with the butt of his gun, as the Governor’s Secretary stepped forward with a number of free farmers, who without permission commenced to choose the fittest from the newly arrived felons.

“Governor’s choice first,” the secretary demanded, instructing the number of soldiers standing idly to the side to move the settlers back from the convicts, as the women prisoners from the ship were hurried away to quarters.

It soon became apparent there would be few choices to work their farms, as even the fittest of the group would need some time and rest to be capable of performing the simplest task. Yet with expert eye and experience the secretary selected a number of poor wretches and directed the officer to convey them away, the remaining were fair gain for those in need of free labour on their selections, with the only obligation being they must be fed, clothed and be treated with what was considered a fair amount of humanity.

With the last of the worthy convicts chosen and those unwell transferred to the Rum Hospital, there remained three of advanced age and tucked in behind an emasculated lad in his late teenage years whose condition had been overlooked by the convict surgeon.

The lad barely stood under his own strength. Head bowed, eyes not noticing the men in shabby red uniform standing guard over him, nor the gathered crowd, nor was heard their words as each made comment reflecting their own private hell. Himself between conscious and faint but forcing to remain upright, ‘I will overcome this,’ he thought while taking a deep breath and forcing his weakening legs to straight, his back to loose the aching stoop and his head to rise with the last ounce of his remaining pride. Yet the lad saw nothing of his new prison, his eyes drank of its vision but his mind refused the image. ‘Seven years then what?’ he silently asked, ‘it may as well been the rope.’

A farmer noticing the lad stepped forward from the now departing crowd, asking the foreman of convicts to bring the young prisoner closer for inspection. The officer pushed the youth to the front, causing the lad to trip over his leg irons but under the threat of birch, soon regained his footing.

“What is your name son?” the farmer quietly asked.

“Smith,” the youth brazenly growled and received a heavy wack across his bare back from the foreman birch.

“Don’t be bold,” he turned to the farmer, “the useless creature is Edward Buckley, Mr. Wilcox,” the foreman lifted his stick to again strike. As the man’s arm rose above his head the farmer caught it on the down.

“Mr. Smeaton, if you mind, the lad isn’t any use to anyone if he is injured,” Wilcox turned to the lad, “what was your crime?”

“Nothing sir, I did nothing,” he whimpered from the wallop across his shoulders, attempting to sooth the pain away with the palm of his hand, while a trickle of blood escaped from under his wrist irons.

“Liar, it was sodomy Mr. Wilcox,” Smeaton read loudly from his charge sheet, “he’s a filthy shirt-lifter and the pity he didn’t swing for it as was sentenced,” the foreman growled displaying his displeasure towards such an act.

“T’was never proved sir!” the lad protested showing a measure of spirit missing from most of the new arrivals. The foreman once again lifted his stick to strike.

“Mr. Smeaton, leave it be; please arrange for the lad into my care, he appears strong of limb and spirit, I am sure I can make a farmhand out of him.”

Smeaton lowered his stick placing it under his arm; “so be it on your head Mr. Wilcox, besides the waste will feel at home here, a country of shirt-lifters, thieves and cutthroats.”

“Mr. Smeaton he will do, so please make the arrangements to have him transferred into my care.” Once spoken the foreman entered the transfer to his ledger and went about his business.

“Edward is it?” the farmer asked without receiving even a spark of acknowledgement towards his courtesy.

“Then Edward it is, follow me.”

The travel out of Sydney Town was arranged mid afternoon. Samuel Wilcox fixed the lad’s leg irons to a metal ring in the back of his cart and had him sit amongst the provisions purchased from the government store. All this time the young convict had not uttered a single word but had shown a nervous disposition on sighting the number of blacks who either camped in the town or wandered its streets in near or naked state, mostly searching for objects of interest they could be away with. The lad also appeared somewhere between frightened and amazed on seeing his first kangaroo as it bounded through the bushland at the edge of town but it was soon gone and he again settled into a state of apathy and silence.

Some distance from town Wilcox encountered a group of aborigines on walkabout carrying hunting spears; one proudly shouldered a dead wallaby, his back glistening with the animal’s blood. Wilcox waved towards the group as the lad ducked beneath the cart’s seat for safety.

“They won’t harm you boy, it’s only Bennelong and his mob.” The lad didn’t appear convinced.

“Bennelong was a friend of the first governor.” The natives waved back and offered greetings or insults in their own language, as they could well laugh while calling you for being all the dogs of hell.

“Bennelong has been to England and had met the king and I maybe correct in believing he is most probably the only person in this colony who has had that privilege, even as far as to include the governor himself within that affirmation.”

Still the lad remained silent.

“What do you think of that?” the farmer asked.

“Have you met the king?” the farmer continued.

“Can you talk boy?”

“Of course I can,” Edward snapped without making eye contact with the farmer.

“You realise I could release those irons if you promised not to run off,” Wilcox offered without receiving acknowledgement. He allowed his offer to register further before continuing.

“I guess you are like the others,” the farmer released a disappointing sigh.

“Thinking you can clear out to China?” he suggested with a self-agreeing huh.

“Or somewhere – anywhere.” The conversation remained mono-directional.

“Do you know where China is?” the farmer slowed his travel and turned towards his newly acquired farm servant.

“No I guess you do not,” with a clicking of his tongue the draught animal continued.

“I didn’t either until a short while back. Still the farmer’s questions remained unanswered.

“Or you could clear out into the bush,” the farmer suggested and again waited for response. There was still none forthcoming.

“Others have attempted to do so – and many. Yes attempted but most were found soon after, speared through the back by unfriendly natives, their pitiful carcass stinking in the scrub.” Again turning to ascertain the lad’s reaction and finding little the farmer continued.

“Or you could behave yourself and you and I will get along just fine.”

After a number of silent miles the farmer once again spoke, “have you any questions on where I am taking you?” he asked.

“Do I have any choice?”

“So you can talk, no I guess for the next seven years you don’t have much choice about anything but play your cards correctly, life can be at least bearable and in time you could be emancipated and possibly have your own land.”

Some short distance ahead a lone rider approached along the Parramatta road. As the rider drew near the farmer spoke, “good afternoon Mr. Macarthur.”

The rider slowed, bringing his mount beside the cart while appearing to be moderately interested in what was there in.

“Mr. Wilcox,” Macarthur buried his eyes into those of the kid as he addressed the farmer, “Is Macquarie in town?”

“I believe not, he is said to be down at the Liverpool Plains, some trouble with the blacks.”

“What trouble would that be?” Macarthur asked, his interest remaining on the young convict, considering him useful around his growing flock of sheep. Edward broke away from the man’s intensive gaze.

“Some black by name of Bush Mosquito has speared a settler down Mr. Blaxland’s way.”

“Mosquito you say, I thought he was brought in?” Macarthur asked.

“Brought in yes but you know how they are, as slippery as eels.”

“Mosquito,” Macarthur repeated while appearing to drift away from the conversation.

“I believe he was once associated with Pemulway and his son Tedbury?”

“That I wouldn’t know,”

“I guess not,” the farmer concluded, well aware Macarthur knew Tedbury, as he had once allied himself with prosperous farmer, even offering to spear a previous Governor for him but like Pemulway and others Tedbury had gone the way of many of the renegade blacks, now but a memory for the next generation to attach their hopes of redemption from the invaders.

“I notice convicts are entitled to convict labour these days,” Macarthur rudely grunted from a deep belief that once a criminal a man should remain so.

“I have my ticket of leave Mr. Macarthur and a hundred acres under Indian corn to prove my worth,” Wilcox unashamedly protested.

“Possibly so Mr. Wilcox, what is the kid’s crime?”

“Theft I was informed Mr. Macarthur, I believe stealing a loaf of bread to survive.”

“Huh all thieves together, I guess you better watch your silverware – I bid you good day Wilcox.” Macarthur without further acknowledgement recommenced his journey while muttering the woes on interfering authority.

“That was John Macarthur; he is most probably the richest man in the colony. He was Devonshire born, Plymouth I believe. Did you know of his family?”

“No, why should I?”

“By your sound; you are from that part of the country.”

“I was but we were farmers and east of Exeter. Why do you ask?”

“Never mind but be cautious of Macarthur, he has a sharp tongue and some influence and has five thousand acres over at the cow pasture to prove it so,” a wry chuckle, “ hates convicts, emancipists and governors and has the rage of a summer’s storm.”

“Why did you lie to him Mr. Wilcox?” the lad curiously asked.

“Lie?”

“Yes, saying my transportation was for theft.”

“It is my belief that information is your business lad and nothing to do with the likes of Mr. Macarthur.”

Wilcox slowed his travel and pointed to a group of rudimentary buildings sited around a roadside tavern some distance along the rough country track, “ahead is Liberty Plains, we will night there and set out for Parramatta at first light.” Bringing his cart into the tavern yard he turned to his new farmhand, “I should think you have a hundred questions, is that not so?”

“I have learnt not to question,” the lad quietly answered as darkness commenced to gather about. With the darkness came the calls and shrieks of so many animals Edward could not know of, nor their danger. The farmer smiled at the lad’s nervous disposition, remembering his own when he first encountered the southern bush, believing his new farmhand’s nervous disposition should keep him from doing anything silly.

“I should think all will unfold when we arrive home, unfortunately tonight you will remained chained to the cart but I will make sure you are fed and comfortable. Does that appear fair?” The lad remained silent. “I am certain you will feel much better once back on the farm and after a good bath and a change of clothing, then you may commence to see your position in a different light,” once spoken the farmer entered into the tavern.

Alone Edward attempted to find comfort from his leg irons but no matter how he adjusted their position they still chaffed. Tampering with the ring on the cart’s flooring he discovered it to be loose and for an instant believed escape was nigh but loose as it may have been the washers were much to large to be drawn through the hole in the timber. As he tugged and twisted he commenced to realise the farmer’s words, where would he escape to, in every direction there was nothing but thick scrub, darkness and despair.

“What have we here?” A rough voice came out of the darkening night bringing the lad to sharply turn towards the silhouetted forms approaching the tavern. The strangers diverted towards the cart.

“Someone’s pet guard dog to be sure.” The second stranger comically answered. Edward’s heart jump as the strangers displayed interest in the supplies within the cart, “We could do with that lamp oil one admitted while eyeing the bottle of oil to the rear of the cart.

“Ya’ reckon it bites?” The first adjoined and offered his hand as if to pat the lad, only to quickly withdraw as if expecting a nip, while releasing a growling sound. The second growled back. They both commenced to laugh.

“Len Ferguson, Stan Frank leave the boy be.” A woman’s voice cut through the darkness.

“Martha – ‘twas but a little muse;” the first of the strangers protested and with his mate entered into the tavern growling at each other while imitating dogs. The woman approached the lad.

“What is your name son?” She softly asked holding a light high to see him more clearly.

“Edward Buckley,” the lad shielded his eyes from the glare.

“Look at you, naught but a lad and not even an animal should be treated this way.”

Once spoken the woman about turned and was gone. Moments later she returned with the farmer while towelling down his attitude towards human existence, with the man protesting his lack of other choice.

“Bring the lad in Mr. Wilcox and I’ll run him a bath and then get some food into him. Look at his state of the poor wretch, he’s almost dead,” the tavern keeper demanded.

In a back room of the tavern a bath was drawn in a large wooden tub made watertight by an inner lining of canvas. Heated water was brought from the kitchen and once sufficient, the tavern keeper left Wilcox to remove the lad’s shackles to allow bathing.

As the shackles were removed it became obvious how much irritation had been caused by the constant rubbing of the iron on soft youthful flesh and the farmer could almost feel the lad’s torment as memory of his own incarceration returned. The farmer slowly shook his head, “sorry lad but no one should have to endure such cruelty,” yet again his sympathy remained unrequited.

Once the lad was submerged in the tub’s tepid water, Wilcox brought a fresh set of government store clothing from the cart and placed them by while overseeing the bathing. As Edward washed away the grime of his voyage the farmer sat silently as if appraising his nature; eventually he spoke.

“How old are you?”

“Nineteen,”

“Where in Devon were you from?”

“As I said near Exeter and just shy of a village called East Budleigh,” Edward answered with a measure of pride then remembering his loss the spark of pleasure dissipated from his eyes.

“Do you have family?”

“Yes for sure sir, tis’ a large family and,” The lad broke off. For a moment he was back in Devon and it was summer. He could hear the sweet singing of birds and smell the freshly mowed hay but that moment soon became the victim to his reality and again he became silent.

“We are all a long way from home,” the farmer generously spoke but there were no words in his vocabulary that could remove the lad’s grief.

Wilcox watched over the lad as he bathed and remembered his own beginnings in the midlands and how he was also torn away from a family all for the act of pilfering food to feed a mother dying from consumption. He had been in his twentieth year then, turning twenty one on the day he was offloaded from ship to the dock of Sydney, a birthday gift he would never forget and one not realised until some time later.

Now the farmer was closing in on his thirtieth year but felt much older for the experience and the long damp voyage, often laying in bilge water and excrement when the pumps failed. The experience still played havoc with his chest when the weather turned cold.

The farmer’s lot had been fortunate as being able to read and write, was soon selected to staff the governor’s office. It was the colony’s third governor in the guise of Philip Gidley King who, because of his farming background, had emancipated him to farm to produce food for a colony in peril of starvation. Now he was almost respected but never by the free settlers in the likes of Macarthur, while those still in bondage looked upon his emancipation with envy. A man caught between the disdain from free settlers and the envy of bonded convicts.

Samuel Wilcox was tall, lean man, usually of few words but when he chanced to speak, chose those words wisely as, although being considered an emancipists and a free man in the colony of New South Wales, he still had a number of years left of his unusually lengthy sentence, so it would not take a great deal to reverse his favoured position. Quickly he learned to network, as a trusted name and a strong circle of acquaintances was the best protection against those who wished you down.

There were many emancipated folk in the colony, some had reached high places or become businessmen, as in the instance of Robert Sideway, house burglar from London, who became the baker to the marines and in ninety-six opened the colony’s first theatre. One had even been elevated to magistrate for an outlying settlement.

Others, because of lack of opportunity or ability, had fallen back into old ways, either once again finding themselves in shackles working on road gangs, otherwise sent north to Newcastle to mine coal, or gone bush attempting to survive with friendly natives. Usually those would be career criminals and not honest men who had originally fallen down on their luck.

Those being described as bolters who settled with the natives were generally not accepted but allowed to live on the peripheral of their camps. Even taking a native woman did not give them tribal honours but as long as they behaved and refrained from interfering with traditions didn’t find themselves speared and left in the scrub to rot. Some were so disillusioned with white settlement they helped the natives learn ways of fighting back, becoming adapt in guerrilla warfare.

The farmer quietly watched as Edward washed away the accumulation of months of grime and felt well to be away from it all. Happy to be his own man with a future he could never have back in the old country. Could this young convict before him have the savvy, the constitution to also do well for himself, or was he already filled with hate and revengeful fire in his belly.

The farmer had seen many who tumble from privilege after being offered a new life in a new land, far from the degradation of English goals and prison hulks but this could be a cruel country for the naïve, being unforgiving and ready to bring even the bravest, most daring down and one must always be on guard against so strange of elements, yet to date luck and good friends had spared him such grief.

Samuel Wilcox sat quietly watching the lad bathe, eventually he spoke.

“What are your expectations lad?”

“About what sir?” Edward finished his bathing and reached for a cotton cloth left for his drying.

“I guess about New South Wales and your life as a convicted felon.”

“I should think it better than the hangman,” The lad stood fully naked before his new gaoler and felt nothing of it. Privacy had been stripped away on his first day as a convict, along with self worth. Being young and imprisoned with sexually deprived men in the prison hulks and during such a long voyage made him fair game and he soon learned to take what was given without complaint.

“What are you expectation?” The farmer curiously repeated.

“I dunno’ sir,” Edward answered as the man’s eyes lingered on his nakedness as one examining a prize yearling at an auction. They were not cruel eyes, possibly wanting, yet lacked the degrading passion of those interned with him on the Duchess of Devonshire. He turned away.

The farmer passed the lad his new set of clothing and returned to his chair by the door, “I guess it is more what are your expectations of me.” The farmer reappraised his question while his eyes remained on the lad’s nakedness.

Edward quickly dressed and stood silently waiting for his next command. The farmer eventually spoke, “about that promise I canvassed, do I trust you, or should I put you back in irons?”

“I have never broken a promise sir,” Edward honestly but vaguely answered. In truth he could not remember even issuing a pledge of any value, except to a young lad from a neighbouring farm and providence intervened with that promise removing any fault of his own.

“So what is your word?”

“This night I promise not to run away, besides as you said where would I go?”

“Tis’ but brutal truth lad, I’ll have the innkeeper set up a cot in my room for you.”

By sun high the following day the farmer was close to his selection being some short distance to the south west of the village of Parramatta. In doing so was passing a well organised farm, whose main house and out buildings were of grand quality, fitting of any well to do Englishman even in the Home Counties.

“Elizabeth Farm,” the farmer nodded towards the estate and turned to Edward seated unmanacled amongst the supplies in the back of the cart, “it is the property of Mr. Macarthur who we met on the road yesterday and only this month returned from England where he defeated the last Gov’s charge of sedition and rebellion. Now he’s making challenges towards Macquarie.”

“Who is Mr. Macquarie sir?” Edward asked as they continued.

“Why the governor of course,” soon they were passing another plot of land, now wasted but showing it once produced crop, “that my boy was the farm of James Ruse and the colonies first successful farmer, but that was some years past.”

“Doesn’t look much like a farm,”

“He’s gone now and has taken up a selection near the Hawkesbury River on South Creek and doing fine, so I hear.”

The lad remained silent as the colonies history didn’t much interest him any more than the lives and success of its far flung citizens. What interested Edward most of all was how he could survive the next seven years and return to his beloved Devon, or if doing so was even possible, as his sentence of hanging was converted to transportation under the proviso he never again return to England, or if he were to do so, it would be the rope.

“Do you smoke tobacco Edward?” the farmer asked after a quiet moment while watching the lad’s growing interest in the countryside. Now on sighting a bounding kangaroo, it was amazement that overcame him and not the terror of the previous day.

“No,”

“I got you some anyway and it can be traded as I do with my allotment.”

“Allotment?”

“Yes convicts and emancipists alike are rationed a small amount, it is to keep them keen for work and can be used as a stick and carrot to make them behave, otherwise it is withdrawn but usually the military will exchange it for extra sugar or flour.”

“I didn’t know anyone but sailors who smoked back home.” Edward admitted.

“Different here lad but usually the smokers are convicts, emancipists and prostitutes although many convict women also smoke.”

“Do you grow this tobacco Mr. Wilcox?”

“Not allowed to son, it is imported from Brazil, as we must grow food to feed the increasing population and that is not a suggestion but a demand and one followed on by severe punishment.”

Some distance ahead the farmer pointed out one more establishment being the property of Gregory Blaxland whose main property was to the south on the Liverpool Plains but made no comment on the man’s pedigree, only that he and two others, Wentworth and Lawson were gathering supplies and men to travel into the wilderness in search of a way across the Blue Mountains. The farmer pointed to the distant mountains. “They are a barrier to our expansion.”

“Why are they blue?” Edward asked noticing the haze that hung about their lofty existence.

“I can’t rightly say son, I guess god made them so, possibly the devil to dissuade convicts escaping into the interior. That is if you chance to believe in gods and devils. After what I have witnessed over the years, if there is a god, he must hate us all.”

“They don’t appear tall.”

“It isn’t their height that gives problem but the deep ravines and steep cliffs, many have tried to cross but without success.”

“Is China on the other side?” the lad asked, feeling a spark of hope develop, as many onboard ship had made promise that at first opportunity they would escape and travel to China.

The farmer laughed, “China? Someone has been telling you tales; China is only reachable by ship and is almost as far from here as is England, while the closest civilization to Port Jackson is either South America or Cape Town, many believe there is a huge inland sea across the mountains; some said it is the land of King Solomon’s mines.”

“What do you believe Mr. Wilcox?”

“Dunno’ lad, I guess good grazing land, rivers and more natives than I would wish to encounter.”

“Do savages live around here?”

“Some do but don’t worry about the natives.”

“Why so?”

“The poor buggers around Port Jackson and down as far as Botany Bay to the south, have had the natural life drained from them.”

A short distance ahead a small allotment of Indian corn came into view, with pride the farmer pointed to it and two small rudimentary huts close by. “There is my selection.”

“How many acres is it sir?” Edward asked. Being from a farming community he understood such measurement but his recollection was of green pastures with hedge rows and streams filled with trout. Before him was little more than a scar across the land, plagued with tree stumps and rocks surrounded by tall timber and scrub, with the closest neighbour almost a mile distance.

“I couldn’t say lad, I was issued a hundred acres but out here you own what you plant or can take from the blacks but you must admit that is a fine crop of corn,” the farmer explained.

“Take from the black’s sir?” Edward appeared confused as back home to commit such a crime one would be sent to the gallows.

“Some call the land Terra Nullius as the blacks don’t farm in the same fashion we do, so deemed it is for the taking,” the farmer paused while displaying a measure of guilt. He continued; “truthfully the Governor was given instructions to treat the blacks respectfully but how do you live here and not take their land,” with a simple sigh the farmer continued, “besides I believe it too late, the ball is rolling and it’s a very steep slope, so they will need to come along for the ride or go under. Eventually we will become like a spreading disease and one day cover the entire continent.”

“Is that fair,” Edward asked.

“I should think farness doesn’t come into the equation, besides you take you home county of Devon or any other in England.

“What do you mean?”

“Long ago the people of Devon were Britains before becoming but a province of Rome, later they were Saxon then Norman now they are English.”

“I don’t get your meaning,” Edward appeared confused.

“Only that time changes everything and people forget what happened long ago, eventually the natives will be one small part of whatever this country decides to call itself.”

“Do the savages fight back?”

“Sometimes lad but the tribes around here and Sydney Town are somewhat resigned to their lot, most of the fighting was almost ten years back yet on the occasion there is an outbreak, a farmer is speared and blacks killed in retaliation. A hut burned along with a corn field. You kill a child and they will kill a white child.”

“That sits a little like myself,” Edward allowed his remorseful words to exit with regret for doing so, breaking a decision made while on the long voyage, being he would shrink back into his spirit, his very essence as if the cruel unrelenting world around him did not exist. Instead he would silently accept his grief until snuffed from existence.

“You had it bad?” the farmer asked, knowing well of his own transportation leaving emotional scars that would travel with him until the end. Edward refrained from answering. “It will improve, remember that and keep brave.”

The farmer’s words gave rise to hope but with the hope came the memory of the judge’s words, seven years transportation with hard labour, never to return to England, if so the sentence of hanging would be evoked. Never to return was a higher degree of punishment than transportation or the noose. Never to see family, the green rolling hills of the Devon Downs, the bleakness of the Moors and to feel the crisp air of a winter’s day as snow lay heavy on the ground. Most of all it was the separation from a friend who he held more dearly than family, farm or crisp winter’s day.

“Come on then let’s get us home, there is work to be done.” The farmer spoke while encouraging his old horse from snatching a quick feed from the long dry grass beside the dusty track.

“Are you wed?” Edward asked as they came onto the selection, expecting to encounter a smiling face advancing to meet them, her man back from town with much needed supplies and a hungry stomach. The farmer didn’t answer, the solitude of the hut would do so, besides he could not answer truthfully otherwise secrets locked deeply in his mind may lose their disguise.

“I’m sorry sir, I didn’t mean disrespect,” Edward quickly apologised, noticing an air of discomfort come over the farmer.

“No trouble lad but in private you can call me Samuel,” he paused and laughed; “back home it was Sam but that was then and cannot be so again.”

“What is your preference lad, Edward or Ed?”

“Edward I should think, I have never liked it shortened as it sort of discounts the wishes of one’s parents.”

“So Edward it is,”

Truthfully Edward was quite fond of the shortened version of his name but it had always been reserved for a special person, one whose memory he must keep within his thoughts and a face that he feared in time would be lost to his inward mind, so he must fight to keep it fresh.

He was but a child when introduced to a neighbour’s boy. What is your name was asked – Edward it ‘tis. Than to me it will be Eddie and you can call me James and that cannot be shortened, except for Jamie or a single J but that would sound somewhat silly.” Edward smiled with that long held memory but as quickly pushed it away before his sad displeasure could be noted.

“Did you parents have a farm?” the farmer asked as he jumped down from the cart.

“Yes we also had a number of dairy cows and some of Devon Black pigs.”

“What about crops?” The farmer went from the cart and appeared to be searching the ground for something.

“Mostly hay and stock feed but mother had a wonderful kitchen garden and -” Edward’s thoughts were running fast, he was again in Devon with farm smells and that of his mother’s cooking filled his nostrils but as quickly he was back, a prisoner in a strange land and he again fell silent as the blunt reality of his situation became obvious.

“Good lad and never lose those memories they will keep you sane and warm on a cold night.”

“What are you looking for Mr. Wilcox?” Edward asked as the farmer scrutinised the ground about.

“Not looking for anything lad, looking at. Footprints, the natives have been around while I was in Sydney.”

“Oh, are they dangerous?”

“Not so much dangerous but they will thieve anything that takes their fancy, as they don’t appear to appreciate ownership.”

Edward gave a rare grin, “then they should be tried and sent back to England as convicts.”

The farmer searched about until satisfied nothing appeared to be missing, “all accounted for,” he sighed in relief.

“What do they steal?”

“They are like bowerbirds and like anything shiny but axes are their favourite that is why I keep my tools hidden.”

“What is a bowerbird?”

“It’s a local bird that likes to gather shiny objects to impress its mate.”

“I don’t have much interest in birds, only the ones we shot back home for pinching grain.” Edward admitted.

“You’ll get to know them here lad, plenty of time to do so. There are birds that call the coming storm, others when snakes are around.”

“I don’t think I wish to stay long enough to become so accustomed.”

“Seven years wasn’t it?” the farmer asked.

“It is,”

“More than enough time my friend.”

Gary has brought us several fine works, featuring Australia and its history. While they are all gay oriented, they are always thought provoking. Let Gary know you are reading: Gary dot Conder at CastleRoland dot Net.

48,226 views